I recently came across the concepts of clock time and calendar time in an essay by Patrick McKenzie (@patio11 on twitter).

Clock time is the actual time it takes for you to do an action (send a mail, draft an article and hit publish, code a change and set up an A/B test etc.). Calendar time is the period in which the impact / consequences / results of the above clock time action play out. In Patrick’s essay, the example is of A/B tests which take 15 minutes to set up but a week to play out; another example is publishing a blog vs waiting for Google to index it (say 3 days). Apply to a job in 30 mins (clock time) and wait for a week to hear back from them (calendar time). And so on.

Introducing Work time and Impact time.

I want to extend this now to create 2 related concepts. The first is the concept of Work Time. This is the total time required to create something – this includes Clock Time which is the actual hours of sitting and grinding, plus any Buffer Time required. For a book, the Clock Time may be 2 hrs a day x 300 days of writing in a year equalling 600 hrs, but with Buffer Time – the time for researching, sleeping, ideating etc. – added, the actual work time is a year. Impact time is the period in which the results or effects of what you did in Work Time plays out e.g., if the book mentioned above is a massive hit and sells for the next 20 years, then the Impact Time of the book is 20 years.

Example 1: So it takes 5 hours for a podcast episode to be recorded, cleaned up and published. This is work time. Then you release it and it takes 7-10 days for the audience to consume it and react on social media. This is impact time. Theoretically, your Impact time in this case could stretch, but assume that this podcast is topical and that no one will listen after 7-10 days.

Example 2: You send out a mail saying X is the new annual leave policy – let us say thinking through the policy and drafting it out along with the mail takes you 3 hrs. But the impact of that on the organisation is the year. So Work Time is 3 hours and Impact Time is 1 year.

Understanding our jobs in terms of Work and Impact Time.

It is interesting to take these two concepts and apply to the world of professions. Surgery, law, therapy etc., are all professions where you can only earn on Work Time (you only get paid for the hours you work). Your Work Time labours have impact – a surgeon’s efforts lead to recovery and healing, but you cannot charge for that impact separately. This is essentially true of almost all services. Here, you are selling time or labour, in most cases in the presence of the customer; and you can only charge for the time you are spending with the customer while delivering the service. There are exceptions, e.g., a contract can be drafted without the customer being present.

The opposite profession is where you make and sell a product, such as writers publishing books, musicians who create albums, moviemakers, software engineers making apps etc. Here you create the product on Work Time but earn over Impact Time which can be anywhere from very short (the product bombs) to eternity (the product becomes a cult classic). Hemingway died in 1961, but every year, a 100k or so (I presume this but I could be wrong) of a ‘A Farewell to Arms’ gets sold.

Do note that when you create and sell a product, you need to survive on your own for the Work Time. A book’s Work Time may be a year and the writer has to survive on his savings (or if lucky, an advance) during this period. And of course, there is no guarantee if there will be any earnings in Impact time (or even a long enough Impact Time). In the case of services sellers such as dentists, or a fitness trainer, they earn a basic minimum income through the 6-8-10 hours of Work Time that they put in (or rather sell to their clients) everyday. There is an upper bound on their earnings though. The average dentist does very well compared to the average writer, but the best (or most famous) dentist can never hope to even reach 1/100th the earnings of the best / most popular writer. There are additional nuances as well – a surgeon or a teacher’s reputation grows in Impact Time and influences her ability to set a higher rate for her Work Time. Thus there are interplays between Work and Impact times as well.

Effectively, all products have Impact Time earning potential, whereas all services have Work Time earning potential only. But Impact Time earnings can be zero (or infinite), where Work Time earnings have lower and upper bounds as set by the market.

From professions to tasks, and understanding leverage and dependencies.

If you can do an action in 2-3 days, but the impact of it plays out over the next year or so, then it is a great example of a high leverage task. A good definition of leverage in tasks or To-dos is low Work time and a long Impact Time. Of course, determining or estimating the full extent of impact in advance is not easy – you do have a reasonable idea of how long the results will play out, though the quantum of impact isn’t always clear. e.g., if you spend a day drafting the pricing policy for the coming quarter, then you know it is high leverage (1 day of Work Time vs 90 days of Impact Time) even though you don’t know the actual business impact, what profits will come out of that.

Allocating your Work Time to high Impact Time tasks (or high leverage tasks, they effectively mean the same) or prioritising your calendar towards such tasks is a no brainer. Also, the higher up you go in an organisation, the more the need to make sure that you are focused on high Impact Time tasks. If you are the CEO, it is too expensive for you and the company to have you do any primary work (draft a note, create a powerpoint deck) if it is not high leverage.

You should also prioritise your calendar to doing tasks without which another person can’t start their clock time. These are essentially dependencies, e.g., your data science colleague sets out 6 hours today to do an analysis of which customers to prioritise but she is waiting for certain inputs and views from you before she kicks off the task. Hence it makes all the more sense for you to schedule 30 mins in the morning or day before to send her those inputs.

Synchronous and Asynchronous tasks.

Related to the framework of Work and Impact Time is Synchronous and Asynchronous tasks. Does this task require another human being around to be done? e.g., A surgeon needs 5-6 members (anaesthesiologist, nurses etc.) in her team for her to deliver a surgery. Then it is a synchronous task. An accountant and her team spend 3 hours reviewing a customer’s accounts and recommending some actions. The client isn’t present when they work. This is an asynchronous task.

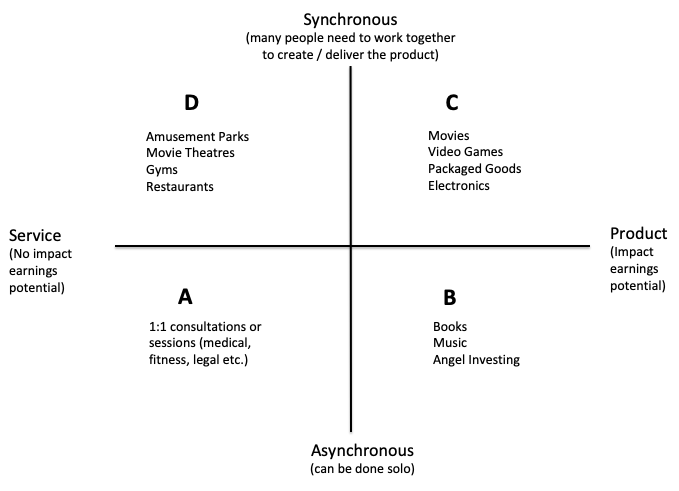

Here is a 2×2 chart of synchronicity x impact earnings potential –

Moving across the boxes.

It is interesting to see the rise of the gig economy as the movement of more and more jobs from D to A. COVID too is spurring this shift. If you are a fitness instructor who is part of a physical chain, it cannot open due to COVID, you can now become a free agent and start off earning via 1:1 or 1:few zoom or whatsapp classes. You thus move from D to A.

But well before COVID too, there were folks moving from D to A. You could go from working in a restaurant as a full-time employee to being an agent on Pared, a U.S. app that helps restaurants staff on-demand. Similarly in India a barber could leave a salon to join Urban Co as an on-demand agent. Now this can be seen as positive, in that it reduces the dependence of the worker on an establishment and enables the worker to earn more, or a negative helping the restaurant or establishment move out workers to an on-demand platform, hiring them only as needed.

And it is not just restaurants – the rise of Wonderschool (childcare), Playbook (fitness), Dumpling (personalized shopping) are all examples (U.S. only as of now) of tools that help the service-seller unbundle their profession from employment and monetise better.

Similarly there is also a parallel move from C to A, where product organisations are unbundling asynchronous tasks out of the org, by paying for time for creation, e.g., pay for subtitling to a freelancer instead of having someone in house for that. Eventually any asynchronous task, i.e., that doesn’t involve close real-time collaboration will get bundled out of the organisation. The only people left in the org will be those who collaborate closely in near real-time, and whose jobs if moved out of the org will increase coordination costs. The Coasean boundary will shrink to encompass synchronous workers largely, and ideally those whose contributions are high leverage in some way.

It is also interesting to see the rise of Teachable, Substack, Patreon, Kickstart as the rise in the numbers of people planting their flags in the ‘B’ box, as they create writings, videos or artifacts that either help them earn in Impact Time, or help build their personal brand and reputation that they can monetize through higher rates in Work Time. The highest earning work time sellers invariably have products (writings, videos) that build their reputation or earnings as they sleep, e.g., the wealthiest chef has a TV series. This increase in the number of people operating in the B Box is the rise of the passion economy, as Li Jin puts in her well-known essay.

What Substack, Patreon etc do effectively is a) help creators connect directly to their fans as opposed to being curated by an editor or similar intermediary b) make it easy to earn money in trickles than wait for Impact Time. This helps make it easy for more and more people to go plural and play in the B box too.

What does Machine Learning (ML) do to these boxes?

How would the relentless improvement in Machine Learning + Robotics play out?

If ML can learn from past situations to extrapolate to newer situations, then it stands to reckoning that the territories that are safest from its grasp are those where you cannot extrapolate from past learnings easily. Jobs that demand creativity, especially split second creativity basis gauging a counter party’s mood, e.g., an advocate or a surgeon’s job. Surgery, in fact, seems like the last job machines can replace – it requires extreme motor ingenuity as well as real time innovation. Or e-sports. Effectively we can say that if the service involves 0->1 real time creativity, gauging of body language / motor ingenuity then it is safe to say that it is protected from the advances of ML and Robotics. Another category of safe jobs is where human intimacy or attention is the product being sold.

It isn’t like machines or robots wont enter the space of human intimacy or affection. Replika is an ‘AI companion’ app

that wards off loneliness and provides counselling. Apparently 40% of its 500k audience bases has romantic feelings for their Replika (Mario’s The Generalist substack). So, perhaps, the world we are moving towards is a 2-tier one. One tier for cheaper machine-led solutions, and the other tier for human-led. So GPT-3 and GANs and Deep Fakes could give us books and videos generated through machine creativity. This could be sold at lower prices, while the rich consume human-created art – books, music, films.

One way to distinguish human vs machine creation might be real-time creativity. Perhaps the ultimate idiot-proof restaurant of the future is where the chefs whip up any dish the customers can ask for (basis available ingredients) from scratch, instead of only offering menu-based dishes. Or movies that are being transmitted live as they are shot, with the audience being able to change the script real time (akin to a live reality show or live sports).

I fear this post has gone on too long already. We started with defining new time units, then jumped to its impact on tasks and professions. We created a framework to understand the rise of the gig and passion economies, and have now arrived at what machine learning advances mean really for professions. It is time to put a stop and to hear your thoughts.

September 12, 2020 @ 11:20 am

That’s a very well written post.

Loved some interesting yet simple concepts like work time, impact time, synchronous and asynchronous tasks.

These are stuff that are known yet not thought/brought out in this way.

Kudos again!