“Early stage valuations aren’t really valuations. They are the exhaust fumes of a negotiation about two things – the amount raised and the amount of dilution.” – Fred Wilson; source.

“Those guys are morons,” says Palihapitiya of many value investors. The historic way of determining value by looking at balance sheets and discounted cash flow no longer works, he asserts. “Today, when money has no value, because we’ve essentially printed all the money in the world and we’ll continue to print it over and over, you have to find value in other parts of the balance sheet, so you have to go to things like brand or intangibles,” he says. “And this is where their mathematical models break, and then their brains explode.” – Chamath Palihapitiya; source.

The corners of the valuation room

Around June or July each year, the seed fund where I work holds interviews for the analyst position. Given that we are a small team, a bunch of us in the team, including me, take turns in interviewing candidates. Now, most of the candidates we get are analysts from consulting firms, but a small number of them come from the valuation practices of the Big4 firms. Whenever I interview these candidates, I ask them my favourite interview question: How do you value a startup at our (early) stage?

After 10-15 minutes of back and forth, I take them through why none of the techniques they suggest work, and describe how VC firms actually end up ‘valuing’ a startup (or really pricing the round, to be exact). This is invariably followed by a minute or two of silence or disorientation as their entire mental model of startup valuation takes a hit. The moment passes – the candidates are too polite (or nervous) to argue back – time is short after all, and we change the topic.

A key reason for the disorientation is that candidates are viewing startup valuations from the view of the dominant paradigm we use for valuing companies: Discounted Cash Flow or DCF, which is typically used for listed and mature enterprises. This isn’t unique to candidates. Journalists do this too. We see countless stories highlighting unicorn valuations for loss-making startups; often in these stories, startup valuations are contrasted with those of old economy companies. This is clear evidence that journalists too see the valuations of early stage startups through the lens of the public market.

It doesn’t stop at journalists. Viewing startups as a special case of valuing large (and mature) enterprises extends to financial sector professionals as well, and much of the corporate world too. From that perspective, startup valuations are puzzling to them. The ‘valuations’ are inexplicable given startups are loss-making, and particularly so when profitable listed companies in the domain trade at much lower valuations. Startup valuations seemingly live in the corners of the valuation room that the DCF Roomba cannot reach.

A practitioner’s guide to startup ‘valuations’

This is an essay that I have been waiting to write for the past ~3 years. It distils my learnings, as a practitioner, of how ‘valuations’ work in the venture world. It is the essay I wish I had access to, when I joined the industry. And in writing this, having learnt my way around the venture world the last ~3 years, I hope to enable a greater shared understanding of startup ‘valuations’ among all who have a stake or interest in the startup world. This includes not just those who are looking to join the VC space and want to know the actual mechanics of valuing, but also startup founders or employees who struggle sometimes to explain to friends, families and relatives as to why their firms are ‘valued’ at a certain sum, and even commentators / observers of this space who are curious as to why ‘valuations’ are what they are.

In the essay, I explain how venture valuations are arrived at – not through a technique like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF hereafter) – but via a protocol, or a set of steps, that I refer to as long-term multiparty staging. In explaining how this works in a real life setting, I contrast it with the traditional view of how VCs price / value assets as espoused by a popular commentator on this topic, Professor Aswath Damodaran. Finally I set out the context in which DCF originated – predictable revenue, high cost of capital – and contrast it with the context in which venture operates – low predictability of revenue, and the prevalent low interest regime – and share why we need to stop looking at venture valuations through the prism of techniques better suited for mature companies.

Let us begin.

An hour to learn, a lifetime to master

There is a saying about chess, that it can be learnt in an hour, but that it takes a lifetime to master. Much the same can be said about venture valuations.

Let us understand venture valuations through the prism of a fictional startup that approaches a venture capital (VC) firm for funding. Let us also presume that this is the first time that the startup is raising, and that the VC is a seed fund (typically the earliest institutional investor; and the first to invest ‘other people’s money’, unlike angels who invest their own).

Presume that the startup meets all of the VC’s criteria for being fundable (e.g., MVP ready, early customer validation / pilots underway etc.) and is deemed investment-worthy by the VC. Presume also that the startup hasn’t been able to convince any other VC to invest.

How does the seed VC value the startup? Well, the answer is simple. The startup’s value is the funding amount divided by the equity stake that the startup is diluting. Hence if the startup is raising $1m = ₹7.5crs from the VC, and diluting 20% stake, then the value of the startup becomes $5m, or $1 divided by 20%. (In ₹ terms ₹37.5crs = ₹7.5crs divided by 20%)

That is it. Valuation at this stage (and even for the next 4-5 years and 3-4 funding rounds) is a simple arithmetical calculation. No respectable VC, whether they operate in the seed stage or Series A or finance growth rounds, uses techniques like the Berkus method or Scorecard Valuation method or First Chicago method or even anything resembling the DCF method. (I will cover why in the coming pages).

But I should be clear here. The VC strictly speaking doesn’t set out to value the startup. Yes, the VC does price the share to be allotted to themselves, but this again, like valuation, is a derived outcome of the funding amount and target stake. Valuation is never directly targeted or sought after. Rather, the eventual valuation / the share price emerges once the VC and the founder agree on funding quantum and desired stake.

Now, the funding amount of $1m, and the equity stake of 20%, aren’t just pulled out of thin air. There is a lot of thinking, as well as experience gained over years of investing, that dictates the final specific numbers. The $1m funding amount is the perceived amount thought of by the seed VC to get the startup to the next stage (Series A). The 20% equity stake is what the VC has determined as the desired target stake to hold after the initial round. Long years of investing, or market lore, has informed them that this target stake after several future rounds of dilution will result in a meaningful stake of 8-10% at the time of exit, meeting their internal exit outcomes for the startup[i].

Each VC fund has a sweet spot for its typical preferred cheque size, and its stake target. This is often a range, and not specific figures. Blume Ventures, an Indian seed fund focused on tech investments, and the fund where I work, has a $1-1.5m preferred cheque size, and a 15-20% stake target. We have determined over the previous years of investing, that $1-1.5m is sufficient to cover 15-18 months of burn (revenue less expenses) in the companies we fund, and within this period, they will be able to raise the next round (from a different Series A VC). A 15-20% stake is what we target because we know that a promising startup’s future fundraises will gradually dilute our stake size. Starting with a 20% stake gives us the ability to hold about 8-10% at the time of an exit of $2b or so, a valuation at which we hope the fund winner (there is typically always one in every fund portfolio; if you are lucky, then two) will exit.

It is important to note that this $1-1.5m investment amount, as well as the 15-20% desired stake target can change from investment to investment. There are times when we may pay $1m for 20% stake, and times when we will be delighted to pay $1.5m for 15%. This results in different ‘valuations’ ($1m divided by 20% = $5m vs $1.5 / 15% = $10m). The difference is typically due to increased demand – if there are more VCs competing to invest in the startup, then the funding amount rises, and there is willingness at the VC’s end to live with a lower stake.

It is worth noting that Blume’s preferred investment quantum of $1-1.5m has doubled over the past few years. During our Fund II (2015-18) we determined $500-750k was the amount needed to get the startup to a Series A. Now it is twice that – this is a function of certainly increased competition (demand) at the VC’s end. Supply has risen but not as much as the demand has. Then of course there is the rising cost of customer acquisition as well as the cost of tech talent.

See worksheet titled Supportings for how a fund like ours determines portfolio construction math, resulting in the sweet spot of

- Preferred primary cheque of $1-1.5m (primary because this is the first cheque; there will be some money kept for 2-3 follow on rounds as well; this is the reserve)

- Stake target of 15-20%.

Integral to arriving at the above sweet spot is the split between the primary and reserve. The higher the reserve, the lesser the amount you are left with for primary cheques. A low amount allocated for primary cheques will impact either the number of primary cheques (i.e., portfolio size), or the cheque size itself. Write fewer cheques and you run the risk of backing a smaller portfolio which in turn reduces your odds of finding a hit. On the other hand, if the check size is too small, you run the risk of underfunding your startup, and reducing its probability of getting to the next stage (unless you fund them again to cover the gap, which reduces the available corpus).

A tightly honed portfolio construction and reserve allocation model, as shared in Supportings – triangulating between reserve ratio, the number of primary cheques (and thus portfolio), the cheque size (including your future follow on round allocations) – underlies these sweet spot estimates. Over time every VC fund finds its sweet spots, reflecting its investment approach, which in turn determines staffing (the more the number of primary cheques, the more investment leads or Partners you need) as well as its deal flow creation + evaluation system.

Introducing multiparty staging

Now we can perhaps better understand the quote by Fred Wilson, that I shared at the beginning of this essay. “Early stage valuations aren’t really valuations. They are the exhaust fumes of a negotiation about two things – the amount raised and the amount of dilution.”

It is important to understand that when (seed) VCs back early stage startups, there is very little data – performance or financial – that is available. The VC is fundamentally betting on the team, the size of the problem they are after, and their ability to create and execute on the product / solution to the problem they are after. At the time a startup approaches the VC, little is clear – how well the startup might do, how fast it could grow, how profitable it may become, how much money it will need to execute, etc.

The VC can, of course, sit alongside the startup and attempt to chalk this out. But they both, and the ecosystem knows that will really be excel storytelling. No one really knows what this will all amount to, and yet the team needs the money now. So how do we determine how much to invest? The solution that the US early stage / venture ecosystem arrived at was to ‘stage’ fundraising in a series of steps, and give only as much money as is required to reach the next stage or level.

Staging[ii] works like this: angels / microVCs back idea-stage or near idea-stage startups to reach the stage at which a seed VC would fund them. The seed VC funds the amount that should propel the startup to reach the stage at which a Series A VC backs them. The Series A VC then funds them to get to the stage at which a Series B backs them; and so on till the IPO. Each stage has a funding amount (and a stake target) along with a rough set of qualifying criteria. Over time, VCs have specialized the formula for the stage in which they play in. The chart below outlines this:

| Stage | Qualifying Criteria | Funding Amount | Dilution | Derived Valuation |

| Pre-seed | Worthy idea / some customer validation | $250-750k | 10-15% | $2.5–7.5m |

| Seed | MVP / Customer validation / Revenue from 1-2 customers | $1-1.5n | 15-20% | $5-$10m |

| Series A | Product Market Fit / Annualized revenue of $500k-1m | $5-10m | 15-20% | $25-65m |

| Series B | Successful scaling of GTM playbook / Annualized revenue of $3-5m | $15-30m | 15-20% | $75-200m |

| Series C, C+[iii] | Successful scaling / adding new product lines or new geographies / annualized revenue of $10m+ | $50m+ | 10-15% | $300m+[iv] |

Multiparty staging over long time horizons

As we saw earlier, staging the fund raise required by the company to grow to IPO across multiple rounds, achieves two broad outcomes

- It reduces the total amount of capital at risk, as the startup is able to access the next round of funding typically from a different VC; and this will usually only happen if it achieves certain milestones.

- It allows more players to collaborate in valuation discovery.

Let us double click on this. Let us go back to our earlier story of the fictional startup and the VC. Imagine that 12 months have gone by. The startup is doing well; the go to market approach has been perfected and it is yielding results. There is immense demand for its products, and the startup has had to continually hire people. Product-market fit has clearly been achieved. Let us say that it is nearing an annualized revenue of $500k (Annualized revenue of $500k-1m is a kind of norm for Series A fundraises). At this stage, let us say the seed VC introduces the startup to a bunch of potential Series A investors, and one of them decides to back this company.

Like with the Seed VC, the Series A VC, too, has its sweet spot – for the Indian market it is $5-10m and a minimum dilution of 15%, though preferably 20%. This effectively sets the ‘valuation’ range from $25m ($5m divided by 20%) to $66.7m ($10m divided by 15%). Let us say in this specific case it is $7m and a dilution of 17.5%, and thus we arrive at the resultant ‘valuation’ of $40m.

Let us consider an alternative scenario.

What happens if, say, the startup’s performance is not good, and it is not able to raise its Series A? Well, in all likelihood, the seed VC will extend a bridge round of $250-500k to help the startup buy some time, and pivot / improve. But if the performance still doesn’t improve, and the startup hasn’t had any luck in attracting any new investor(s), it is very likely that the seed VC will, at this time, desist from funding the startup any more. In all likelihood, the startup will die.

Lest you think that the seed VC is the villain, do note that the startup founders will be equally keen to move on. The opportunity cost of the venture is high, and they will be keen to move on to another startup, or even join a stable company for a while as an employee to recoup some savings before the next venture. It is very likely that the seed VC could fund this venture too. In the startup world there is no stigma to failing at all, and relationships rarely fray or sour between VCs and founders in case of a failure. More on this later.

Let us get back to our startup, and presume that it is now raising a Series B. Much of the same construct holds at Series B too. A different VC comes in to bear the risk and fund the startup to the next stage. Their investment and dilution sweet spot determines the valuation again. Eventually as the startup grows, and as its revenue gets predictable, later stage investors begin to use standard valuation techniques such as DCF, public market comparables with desired adjustments or revenue multiples etc., to ensure that the valuations aren’t too out of whack. Eventually as the startup gets closer to listing, the valuations converge with those of similar listed entities.

This gives us a sense of how startup valuations are determined.

They are essentially derived values (from stake and funding amount), resulting from multiparty staging games conducted over 5-7-10 years, until the startup becomes akin to a listed entity. Early stage and even early growth VCs don’t know what the ‘valuation’ of a startup really is, but it doesn’t matter. For, the long term, multiparty, coordinated staging game[v] that VCs have arrived at over long years of iteration, allows them to collaboratively price the entry share price for the startup at each stage. It doesn’t matter if at each stage the resultant valuation is not exact or correct. It helps that that each stage is connected to the next stage, and allows for some correction[vi]. It also helps that there is increasing predictability of revenue and metrics as the startup grows, allowing the valuation to converge with public market valuations.

| Early stage startups | Late growth startups | Listed entities | |

| Predictability of revenues | High unpredictability | Medium to high predictability | High predictability |

| Growth | Extremely high (>100% annual) | High growth (30-70% annual) | Low to medium growth (2-10%) |

| Valuation | Derived valuation via sweet spot | DCF / Public market comps / Supply & Demand along w sweet spot led derived value | DCF |

| Liquidity of stake for founders | Zero; founder(s) selling equity is a bad signal | Limited scope for liquidity; investors allow a small percentage sale | High scope for liquidity; negative signal though |

| Liquidity of stake for investors | Virtually zero; investors exiting the co will destroy the co. | Medium liquidity; 25% or so discount on valuation / share price while exiting | High liquidity; no discount during exit. |

An important aspect to be kept in mind is that the concept of valuation and value is notional at the early stage of a startup. Yes, you are a founder holding 20% stake in a Series-B funded co valued at $150m. Yes, you have paper wealth of $30m (20% of $150m), but if you want to exit the company at this stage, and sell your shares to retire, then the value of the company will plummet, and this will prompt the VCs to mark your holdings down to book value (which will be a pittance). This makes early stage valuation intrinsically different from that of publicly listed company valuations. The owner of a publicly-listed co can sell his or her shares easily, though it can be read as a negative signal.

Capital is signal

Every investment action and offer of a price by a fund in the venture world is a coded signal to other VCs, typically of confidence in the long-term prospects of the company. A seed fund will not invest in a startup if it is uncertain whether the Series A fund will play in 12-15 months, who in turn will opt out, if it thinks the Series B fund might not engage; and so on. will not play if they think the Series B fund will not play; and so on. So when a seed VC invests $1m to pick up a 20% stake in a startup, it is signalling to all the Series A folks – “Hey, here is a high quality company that will be coming your way in 15 months.”

Conversely, if the seed fund decides not to play its prorata (the share of a follow on round it is entitled to play for) when it has historically done so, it is a clear negative signal to other investors; similarly if it chooses to sell its stake, that is an even stronger negative signal.

Every investment action is also a coded signal from the VC to founders. If the VC sends out a term sheet with 2x participating liquidation preference (a particularly founder-unfriendly clause), this is telling the founder something.

Signalling is inherent in the multiparty staging games being played out between different VCs and founders. Whether you wish to signal or not, if you are part of these long-term multiparty staging plays, each of your actions as a VC is sending out a signal[vii].

A critique of Prof Aswath Damodaran’s piece on how VCs value / price; introducing signalling

While researching this piece, I came across an article on how VCs value / price assets, from Prof Aswath Damodaran, one of the doyens of valuation theory. In this article, titled ‘Venture Capital: It is a pricing, not a value, game!’ Prof Damodaran offers his take on how VCs value the companies in which they invest, outlines the different approaches they take to valuing them and provides critiques to those approaches. I couldn’t help shaking my head as I read through the post, given how much the practices mentioned in the post seemed at odds with reality. I thought it would be useful for readers to see my critique of Prof Damodaran’s views on venture valuations. Through this contrast, I will reinforce the previously introduced long-term multiparty staging protocol; further I will introduce the concept of signalling inherent in long-term staging practices.

Back to the article. Prof Damodaran details out four methods – recent pricing of the same company, pricing of similar private companies, pricing of public companies with some adjustments and finally, forward pricing – that VCs use to value companies. From the methods, you get the sense that he is referring to late stage VCs (growth funds / hedge funds etc.) but he does specifically refer to the last method, forward pricing, as applicable to young startups.

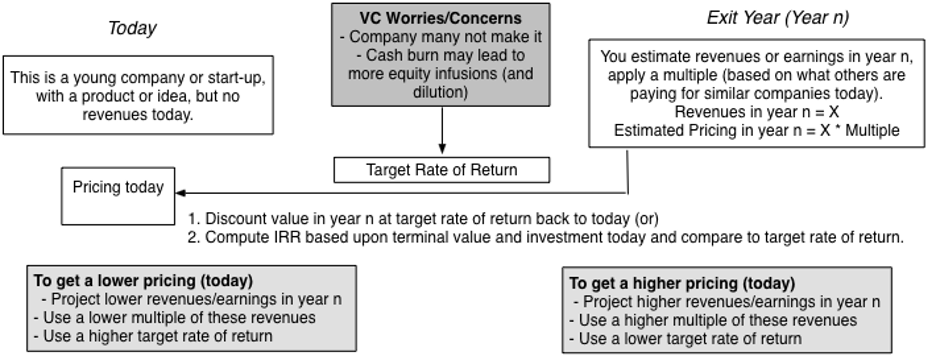

He writes: “Forward pricing: The problem with young start-ups is that operating metrics … are often either non-existent or too small to be base a pricing (sic). To get numbers of any substance, you often have to forecast out the metrics two, three or five years out and then apply a pricing multiple to these numbers. The forecasted metric can be earnings, or if that still is ephemeral, it can be revenues, and the pricing multiple can be obtained not just from private transactions but from the public market (by looking at companies that have gone public). That forward value has to be brought back to today and to do so, venture capitalists use a target rate of return. While this target rate of return plays the same mechanical role that a discount rate in a DCF does, that is where the resemblance ends. Unlike a discount rate, a number designed to incorporate the risk in the expected cash flows for a going concern, a target rate of return incorporates not just conventional going-concern risk but also survival risk (since many young companies don’t make it) and the fear of dilution (a logical consequence of the cash burn at young companies), while also playing role (sic) as a negotiating tool. Even the occasional VC intrinsic value (taking the form of a DCF) is a forward pricing in disguise, with the terminal value being estimated using a multiple on that year’s earnings or revenues.”

Prof Damodaran shares a chart explaining the above.

Prof Damodaran concludes: “At the time of a VC investment, the VC wants to push today’s pricing for the company lower, so that he or she can get a greater share of the equity for a given investment in the company. Subsequent to the investment, the VC will want the pricing to go higher for two reasons. First, it makes the unrealized returns on the VC portfolio a much more attractive number. Second, it also means that any subsequent equity capital raised will dilute the VC’s ownership stake less. If you reading (sic) this as a criticism of how venture capitalists attach numbers to companies, you are misreading it because I think that this is exactly what venture capitalists should be doing, given how success is measured in the business. This is a business where success is measured less on the quality of the companies that you build (in terms of the cash flows and profits they generate) and more on the price you paid to get into the business and the price at which you exit this business, with that exit coming from either an IPO or a sale.“

Prof Damodaran’s conclusions seem logical but I believe he is wrong on two counts. First, I have never come across this target rate of return method. Neither have we ever used it at Blume, nor have I ever heard of any VC at our stage or even beyond who uses it. Perhaps there are hedge funds who use it. But he pointedly refers to young startups (in the first of the two paragraphs above), so he is referring to early stage VCs who use this technique. I look forward to hearing from my readers who work in US VCs if they think otherwise, but I doubt that forward pricing in the way Prof Damodaran has detailed, is used in early stage US venture funds. Second, a key assumption he has made – that VCs want to enter cheap by pushing for a low entry price, and then want the price to go higher – is wrong. This seems logical, after all the cheaper you enter and the higher it gets, the more the profit. Moreover, this is exactly how it works in public markets, but in private markets like venture, there is a twist.

In private / venture markets, the parties who enter at different stages know each other well, unlike public markets where the parties who buy and sell are relatively anonymous. Blume, for instance, knows many MicroVCs and angels who refer deals to us. We in turn refer many deals to Series A companies, who also refer deals to us. We also know many Series B investors who play in investments. Similarly we know many of the founders in our ecosystem well. We are hugely dependent on them as well as our own portfolio founders for our referrals. In the venture / startup world where you play long-term multiparty staging games, there is no anonymity.

With the above context in mind, let us visualize a situation that Prof Damodaran alludes to, where the VC intentionally pushes down pricing, and then pushes up pricing (if at all this happens!) Let us look at what this signals, and if so what these signals imply for the VC’s brand in the reputation market.

- Founders in general will talk about the VC to other founders who approach them as “Hey that VC is no good, they squeeze you hard and are not generous. Stay away.” This cuts off deal flow.

- The founder of the company whom the VC has given lower prices to, will also tell founders who approach them, “Hey, look what they did to me. Stay away.”

- Series A VCs who are in the next stage will say – “Hey, the last deal these guys brought to me, man, they pushed up the premoney on the deal, and I didn’t get as high a bump up when the Series B guy came in. Hey, I don’t want to work with these folks given what they do. And guess what, this early stage founder who approached me, I told them to stay away from them because they underprice and undervalue deals.”

I would thus argue that the short-term bump that the VC gets on a deal, would be nothing compared to the long-term reputational loss from the signals that the VC sends through those actions. If deal flow gets choked, and the highest quality founders move away, the VC’s brand is damaged. The VC is in fact very careful about signalling behaviours that may be seen as unfriendly to founders. A good example of this is that markets like California which have high competition amongst VCs also have the most founder-friendly terms (Bengsston and Ravid, 2009).

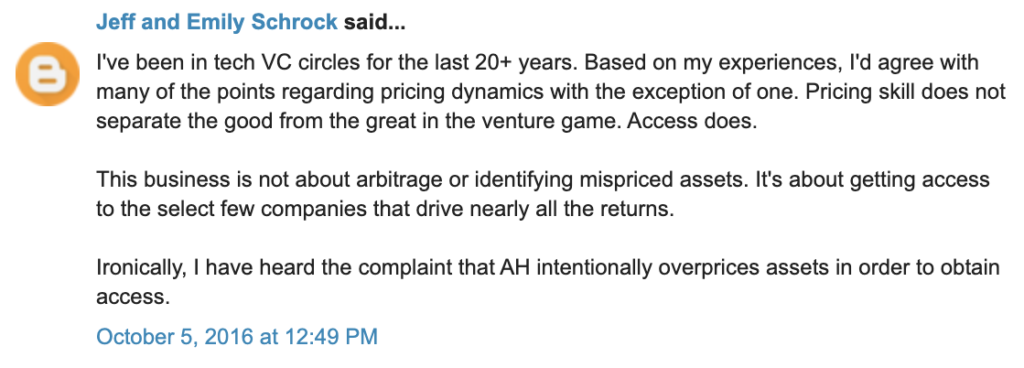

Hell, if the VC fund is smart they will actually overpay for deals. That signals supreme founder friendliness, and will help them attract more deals. Which is exactly what a commentator is suggesting below (from the comments to Prof Damodaran’s article).

Founder friendliness, and signalling founder-friendliness is key to ensuring access to the best deals. For the highest quality deal flow typically comes from referrals made by founders. VCs won’t do anything to upset relationships with founders as the last thing they want is an upset founder who doesn’t introduce them to the new promising founder on the block; who then goes on to build a unicorn, with the support of another VC.

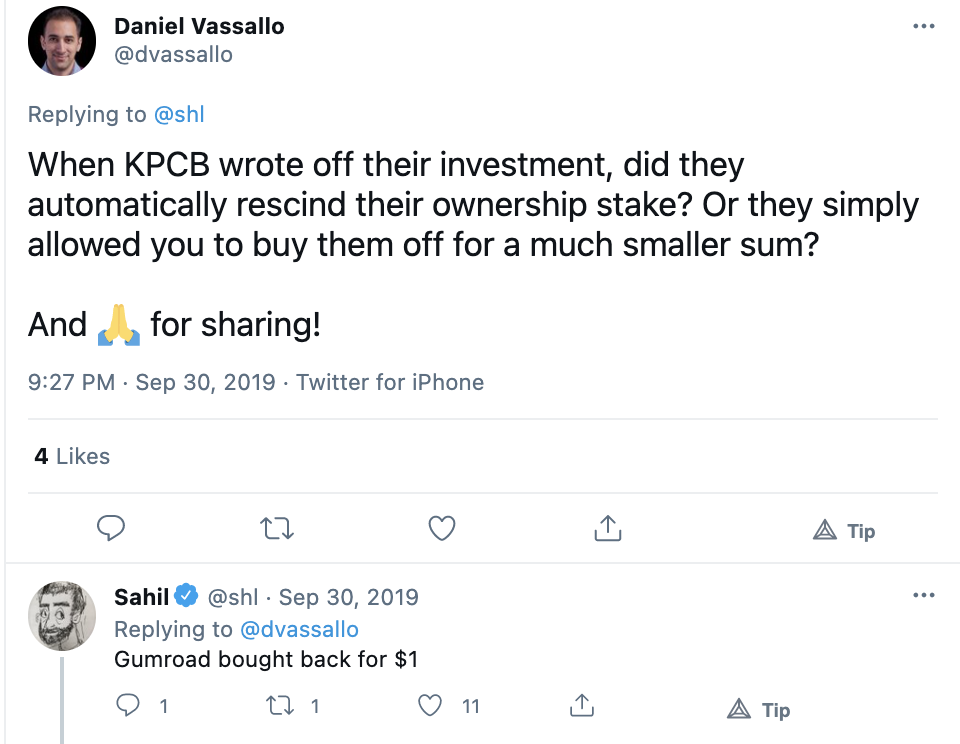

This explains why VCs indulge in actions such as below; writing off the value of their investments and / or selling the shares back for a nominal price to the startup, when it is going through trouble. If you were to go by Prof Damodaran’s logic you would not be able to explain the below.

Source link.

KPCB sold their stake back to Silicon Valley-based Gumroad for $1. Yes, it helped them with some tax gains, but importantly it also meant that they strengthened their relationship with the founder. Gumroad was never going to be a fund returner for KPCB. It thus made more sense to give back the stake to Gumroad, and be in the good books of Sahil Lavingia, the founder, for access to future referrals.

The best VCs play infinite games with other VCs and founders. The best VCs also understand that every action they undertake as part of staging (issuing a termsheet, tranching an investment, playing or not playing prorata) is sending a signal to other VCs and founders (their own as well as the wider founder community). A lot of VC actions start to make sense when you see them as efforts to continually build a brand and positioning with founders (especially elite founders – those who have founded soonicorns+ or are influential in the founder community via their writing or mentoring). Access to high quality founders is the single most important lever in the VC business.

Let us understand this better.

Why access to high quality deal flow matters. A quick detour.

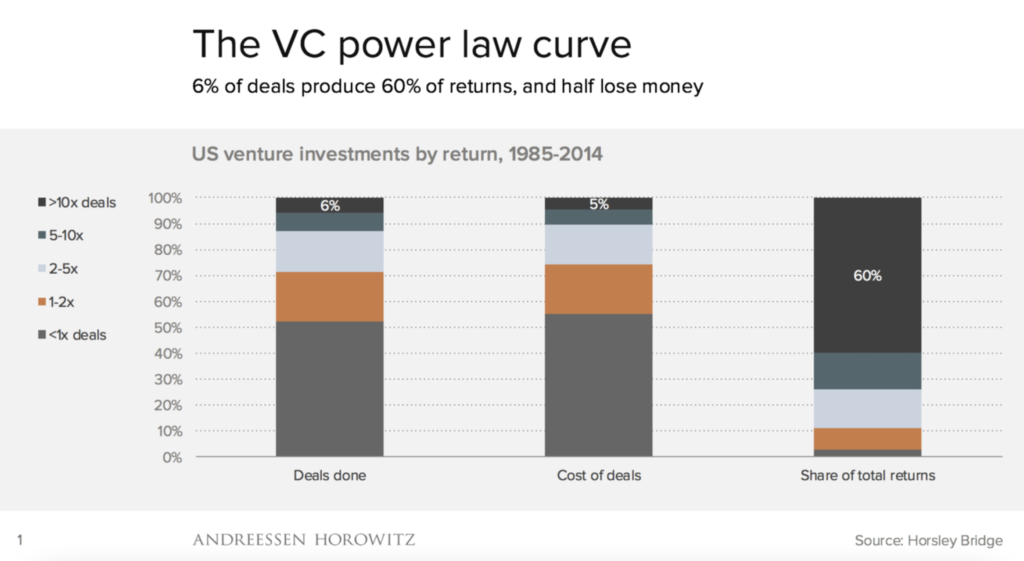

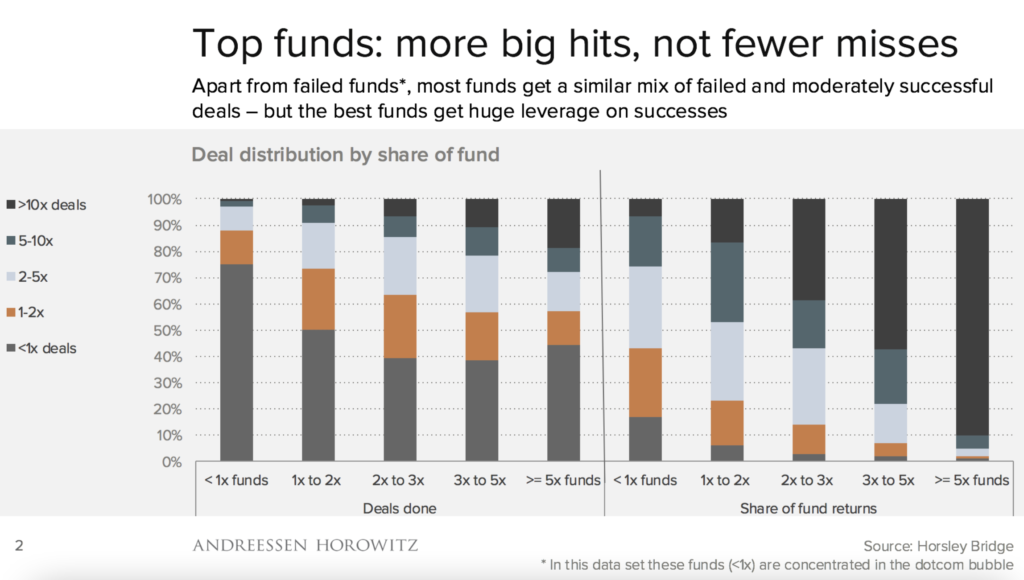

The nature of the VC business is that we are subject to a brutal power law. Much of a venture fund’s returns are powered by 1 or 2 winners. More than half fail.

Here are two great charts via Benedict Evans’s article “In praise of failure”. The first shows that 60% of all venture returns from just 6% of investments.

The second chart shows that for the top funds, the near entirety of returns come from the winners.

Access to these mega winners is the single most critical leverage point in venture capital. For once a VC fund gets a few hits going, a virtuous circle is formed. More high quality founders reach out to the VC, on the back of the hits, and growing reputation. This is an ingredient for better returns, which in turn opens the door to even better founders and so on. This is how the VC flywheel spins.

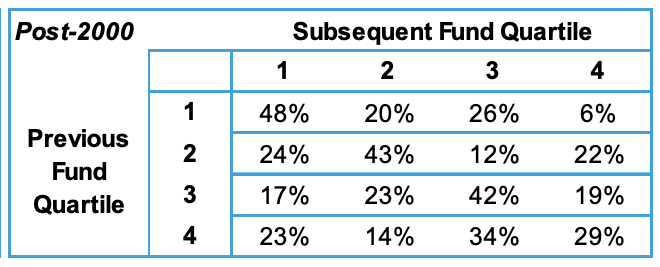

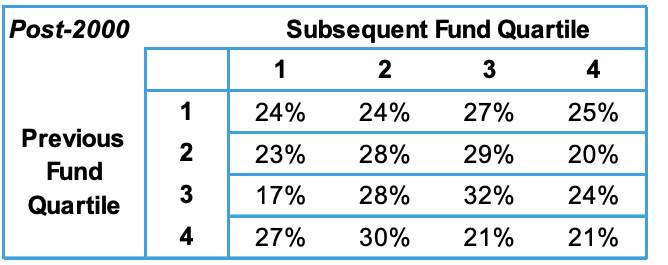

The best VC funds have this unfair access advantage which helps them generate and maintain a returns advantage. This quality is termed persistence (of returns). The chart below shows how venture funds have persistence. If a VC’s previous fund was in the top quartile, then the chances of its subsequent fund being a top quartile fund was 48%. If the previous fund was in the second quartile, then its subsequent fund had a 43% chance of repeating the performance. If it were entirely random, each cell would show 25% as you see in the chart further below – ‘Persistence for buyout or private equity funds’).

Persistence for venture funds

Source of above and below charts: Public to Private Equity in the United States: A Long-Term Look

Persistence for buyout or private equity funds

There is a 24% difference in persistence for top quartile funds between buyout and venture funds. This is what would happen to venture fund returns if we did what Prof Damodaran suggested – driving down entry prices and then bump up prices.

Understanding DCF as a valuation technique for low growth environments and not as a general tool

I will end this long essay with a brief meditation on better understanding the context around DCF.

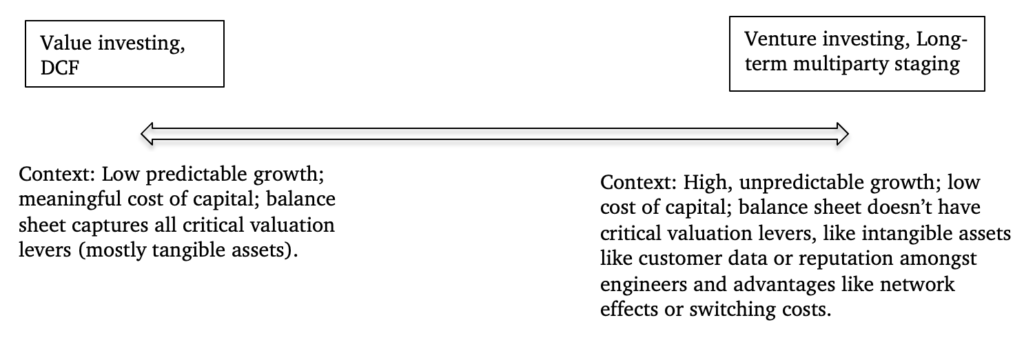

For long, there has been a tendency to see DCF as the default for valuation, the gold standard, the definitive valuation technique. It is well-suited for publicly-listed large companies that have predictable growth, but it isn’t useful for early-stage startups, where there is either no or unpredictable revenues. However, DCF’s hegemony in the valuation arena has meant that startups / VCs have long had to defend their valuations, as if their ‘valuation’ is inferior to that of publicly-listed companies. It almost seems that DCF is the benchmark, and we need to explain any deviation from it, even if DCF is ill-suited for the situation.

I feel a better framework, if that could be said, is to look at DCF as suited to a special context of low or predictable revenue growth, particularly relevant to a high cost of capital regime. Startups fall in the opposite camp.

A similar contrast may be set between value investing and tech / venture investing. Recall Chamath Palihapitya’s quote that I shared at the beginning of the essay – “The historic way of determining value by looking at balance sheets and discounted cash flow no longer works. Today, when money has no value, because we’ve essentially printed all the money in the world and we’ll continue to print it over and over, you have to find value in other parts of the balance sheet, so you have to go to things like brand or intangibles.”

It is not surprising that DCF and Value investing were formulated around the same time – in the 1930s, when the Great Depression was underway. That was a time when capital was scarce (though interest rates were low) in contrast to today where there is a lot of easy money flowing around.

We can therefore contrast these thus –

We thus see valuations done via DCF as a valuation technique suitable for low growth, high (or medium) interest rate environments. In zero or high growth environments with high unpredictability, staging games may be better suited for conducting valuation exercises. It may be useful to see crypto, for instance as uncoordinated, pseudonymous multiparty staging exercises.

Summing up

If you were to leave with one piece of information or understanding from this essay, then I would want it to be the below.

VCs found that the techniques that public market investors used couldn’t hold for younger, fast-growing companies with unpredictable revenue. Through long years of iteration, they came with the practice or protocol of playing long-term multiparty staging games to take the company from idea to IPO. It wasn’t invented by one person or one firm. Rather this evolved like markets do, or cities. Think of it as evolution applied to markets. I personally see these long-term multiparty staging games as one of the great financial innovations of the 20th century, on par with say, credit cards, or even microfinance.

These staging games can sometimes lead to seemingly absurd ‘derived valuations’ at a certain stage. Observers (such as journalists) who highlight these derived valuations and stress on the number, comparing it with public markets are not accounting for the lack of liquidity + covenants such as liquidation preference attached to this derived valuation. These observers do the larger community a disservice with their practices. Over time, these ‘derived valuations’ correct themselves out, and in the long run, as the startups move to an IPO, the values converge with those of their public market counterparts.

Feedback on the essay welcome; you can write to me at sp@blume.vc or DM me on twitter at @sajithpai – do share this ahead if you found it interesting, or know someone who will find it interesting. Thank you, thank you for reading it.

*

I would like to thank Michael Mauboussin for reading a draft version, and sharing his perspectives. In addition to Michael, I would also like to thank Manish Singh, India hand at TechCrunch, Ravneet Dhingra Bawa, a marketer turned doctoral student, and Anand Vyas, a retired investor, for reading early drafts and sharing their feedback with me.

[i] The details are elaborated in the Supportings sheet – cells J17-20 and cell C30 detail the workings. Broadly, a seed fund that enters with a 20% or so stake, can invest in follow on rounds in perhaps Series A and B rounds. Even here it may not be able to get its full prorata (the right to maintain its stake), which is there on the contract but is often difficult to exercise due to practical challenges; rounds usually get oversubscribed in good companies. In following rounds, Series C onwards, the stake then gets diluted, typically by 15-20%. This eventually settles at 8-10% when the company is sold or IPOs, netting in an exit for the VC.

[ii] Staging as a way to reduce risk has been covered by academics studying venture capital, e.g., The Structure and Governance of Venture-Capital Organizations by William Sahlman in the Journal of Financial Economics, 1990. But at no point have they detailed that this is staged across different investors. This matters immensely. If the risk reduces when one investor stages its investment in a startup across phases, then it reduces even more when different investors are involved at each stage.

[iii] Historically, venture ended at Series B or so, after which the startup went for an IPO. Typically it took 3-4 years for startups to go from seed to IPO (Amazon, Google all took similar time frames for their IPOs) but in the last decade or so, timelines have stretched to 8-12 years. A whole new category of late growth investors has emerged including many hedge funds to meet the funding needs of startups, and capture more and more of the value away from public markets.

[iv] As we reach later stage fundraising, the more likely that the startup can be valued like their public market counterparts. There are sufficient metrics by now, and reasonable predictability of revenue. At this stage, with the arrival of late growth investors and hedge funds, you begin to see DCF and / or public market comparables or revenue multiples approaches emerge to benchmark valuations. That said, traditional supply vs demand for stock still remains the primary way to set valuations even at this stage (as companies that are at this stage are hot, in-demand companies).

[v] I shared a draft of this essay with Michael Mauboussin, who heads research at Counterpoint Global, a division of Morgan Stanley. He commented that multiparty staging is a repackaging of option theory. I couldn’t discover any specific paper detailing this though. I did come across papers bringing out how staging was effectively an option. But none of the papers I read mentioned multiparty staging. if readers of this essay find one, please send me the pdf and not the link (as they are paywalled).

[vi] One important aspect we have not covered is the use of legal covenants such as liquidation preferences by incoming investors. Karthik Reddy, Managing Partner at my fund Blume Ventures, describes “these valuations are ‘entry valuations’ – assigned on paper bolstered by carefully-orchestrated liquidation preferences rather than a measure of real worth in terms of actual cash.” Liquidation preferences are first dibs on exit outcomes, such as say a M&A. They favour later investors (last in first out). So effectively, valuations need to seen / read with liquidation preferences. It is no fun if you are a founder sitting on paper cash of $30m, and all your VCs liquidation preferences cancel out your potential exit opportunity.

[vii] A good read on this topic of signaling, as well as venture valuation mechanics is Alex Danco’s wonderful ‘VCs should play bridge’.