I read 22 books this year, of which three were works of fiction. Now I have kept stats of what I have read over the past two decades; I average 23 books a year, about a quarter of which are fiction. Two goals I have set for myself a few years back is to read more fiction, and read older books. On both counts I failed this year. Far too works of fiction, and too many recent reads.

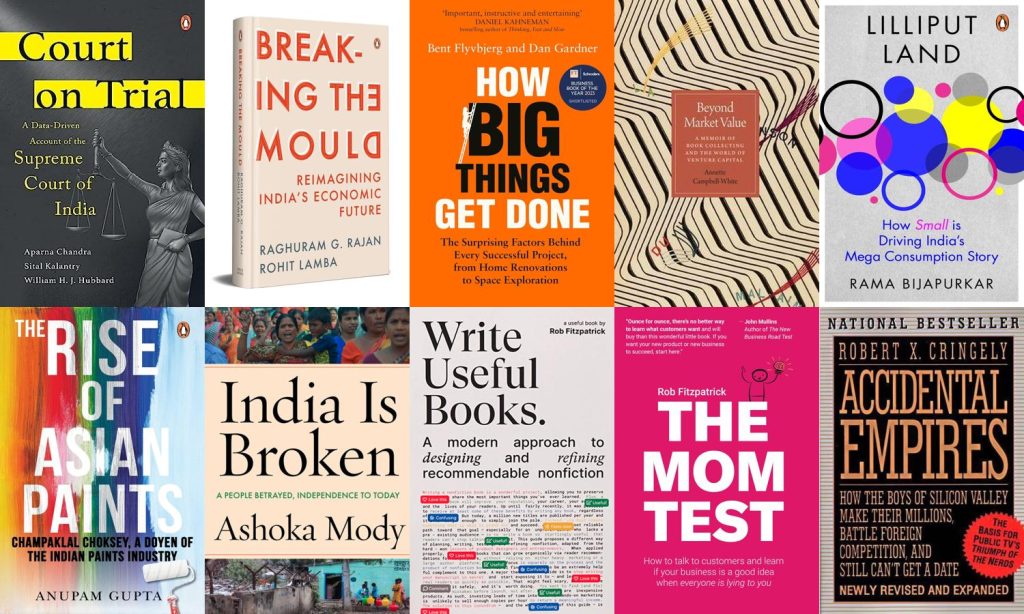

From the 22 books I read this year, I have listed about 10 here, which I particularly enjoyed or recommend.

The first five below are the ones I recommend highly, and then the next five round out the list. There is no particular order in each quintet.

How Big Things Get Done (2023) – Bent Flyvbjerg & Dan Gardner

Bent Flyvbjerg is an expert on megaprojects and why most megaprojects are delayed and overbudget (only 0.5% of megaprojects are under budget and on time he says). In this book, he covers why most megaprojects ‘fail’ and how you can get them done in time and under budget. The mantra is ‘think slow, act fast’, i.e., take your time getting the plan right, and move furiously to execute. Good easy read with lots of interesting examples. Could have been much shorter though, as with all business books.

My summary of the book is here.

Court on Trial (2023) – Aparna Chandra, Sital Kalantry, and William H.J. Hubbard

Compact and enjoyable book reviewing the (mis)functioning of the Indian Supreme Court, through data. Highly recommended. It is surprising it hasn’t created the kind of noise it deserves to, given the topic it deals with and conclusions it derives.

The book was fascinating and infuriating in equal measures. Fascinating, because to a legal layman like me, it opened up the world of the Indian Supreme Court, and the challenges the court faces (the large number of cases, the pendency / delays, the power of the senior advocates, the lack of diversity on the court etc.). Infuriating, seeing the Supreme Court riddled with challenges which it has brought upon itself. The book lays out the challenges the Indian Supreme Court is grappling with, not through anecdotes (though there are some of those in the book) but through data which is not easy to come by, and was painstakingly assembled.

Through this data, the authors come to conclusions such as the Court, in trying to be a ‘People’s Court’, takes on too many cases, and often unimportant ones at that. Most of these cases are of a kind known as SLPs (Special Leave Petition, a provision which was only meant to be used sparingly, but accounts for a bulk of the workload of the court). The court admits a sixth of the ~60k cases it is petitioned (far too much), with SLPs accounting for 88% of these, and passes judgement in ~1k of those. (In contrast, US Supreme Court admits 1% of the ~8k cases it is appealed). Because of the lack of time to deal with the ~10k cases it admits, the ~1k judgements it passes often do not cite legal precedent, give limited guidances to the lower courts, and thus often cannot be used for future judgements.

In different chapters, the authors cover different misfunctioning facets of the court including how the large number of SLPs lead to admission hearings on mondays and fridays, where the ‘elite senior’ advocates get facetime of 90 seconds per case, and charge anywhere from 1L to 15L per appearance. Many of these hearings are influenced by the signaling power (or ‘face value’) of the Senior Advocates. It looks at how the power shifted from judges to senior advocates and asks what can be done to redress that.

Subsequent chapters look at topics such as diversity, political influence, the power of the Chief Justice in determining which judge is assigned to which case, etc. All of these are analysed, and conclusions are drawn through the use of data. Despite all of the legal arcana, the book was an easy read, even for a legal layman like me. It is also a relatively slim read (around 200 pages). Recommended read.

Write Useful Books (2021) – Rob Fitzpatrick

A short and highly readable guide to writing the non-fiction book that dispenses actionable advice, and helps readers achieve their outcomes (books like The Lean Startup, Building a Second Brain etc., which the authors calls ‘Problem-solvers’) as opposed to non-fiction works that are edutainment products such as Malcolm Gladwell or Steven Johnson’s books (which he calls ‘Pleasure-givers’).

Writing a ‘Problem-solver’ needs to be approached very differently, says the author, noting that much of the advice that is usually dispensed for non-fiction books is for ‘Pleasure-givers’. For one, you need to define the scope and the audience tightly enough that there is a strong promise (it is hence ‘Desirable’), it needs to deliver on the promise by offering a high degree of value (‘Effective’), the reader should not have to work very hard to extract that value (‘Engaging’) and finally it needs to be aesthetically designed and well-produced (‘Polished’). ‘Desirable’, ‘Effective’, ‘Engaging’ and ‘Polished’ add to the acronym DEEP, which is a handy way to remember the attributes of a successful ‘Problem-solver’.

Such a DEEP work, he says, will become a self-recommending title, because it is actionable and useful for anyone faced with the problem the book has solutions for. The author shares a lot of useful tips to create self-recommending titles, such as 1) a descriptive Table of Contents, with each chapter’s description being the benefit or value the reader gets from reading the chapter 2) front-loading the value – quickly getting to the meaty parts / main course instead of forcing the reader to consume a lot of starters or front matter 3) having ‘listening’ and ‘teaching conversation’ with prospective readers to validate the Table of Contents, and some key chapters 4) striving for high value per pages turned – reviewing the pages per value or benefits offered, and so on 5) Beta-testing the book with a select group of readers you recruit 6) a guide to self-publish and market the book 7) how to decide on the cover page, and so on. All in all, a useful read for anyone looking to write a ‘problem-solver’.

Lilliput Land (2023) – Rama Bijapurkar

One of the best books I read this year. The book looks at India through the trifecta of its socio-economic-demographic structure, the Indian consumer’s behaviour, and finally the supply structure catering to demand. It says that despite the Indian consumer’s adaptability and their rising aspiration (behaviour), the growth of the economy is held back by a) high inequality and low disposable income for a vast majority of Indians (which is reflected in the socio-economic structure), and b) despite the clear demand for high value, affordable products, the inability of supply structures to cater to this demand (barring a few Indian company, a few Chinese and ecom companies).

The nature of India’s demand – large overall, but aggregated by the small spends of masses (hence the title ‘Lilliput Land’) – means that companies interested in catering to mass India, will need to create ‘Made for India’ products that reflect this reality, providing affordable value to consumers, taking advantage of their high digital awareness and rising aspirations.

The Mom Test (2016) – Rob Fitzpatrick

This is the second book of Rob’s in my shortlist! This is the single best resource for conducting customer conversations better, especially during the problem validation phase of a startup (before you build the product). It is a short book, and the time of 3-4 hours invested in reading it is well worth it in terms of impact.

The name ‘Mom Test’ comes from asking questions in such a manner that even your mom can’t lie to you, because your mom will always think whatever you tell her is a great idea, and respond effusively. Hence your questions need to pass ‘the mom test’! The book encourages you to ask questions about your customers’ lives – “their problems, cares, constraints, and goals” and use these “concrete facts about our customer’s lives” to “take your own visionary leap to a solution”.

The book says that the later you mention your idea to the customer you are interviewing, and even better if you don’t mention your idea, the better the questions you will ask, and the more insights you will extract from the conversation. The book puts it well: “It boils down to this: you aren’t allowed to tell them what their problem is, and in return, they aren’t allowed to tell you what to build. They own the problem, you own the solution.”

My notes / highlights of the book is here.

Accidental Empires (1992) – Robert X Cringely (Mark Stephens)

Fun, racy, spicy, ultra-gossipy read of the history of Silicon Valley, and the shenanigans of the computer pioneers (Bill Gates, Steve Jobs etc) from the 1970s-80s. That said, it goes beyond gossip and funny anecdotes to cover the shifting technological trends and business dynamics of the industry as well. There is also a deep dive into the culture of then startups Microsoft, Adobe, Apple, Lotus etc., as well as behemoth IBM (the best one). Its ability to mix and cover tech trends, business strategy, as well as bad boy behaviour, equally well made it an enjoyable and interesting read for me.

The book became notorious when it was first released in 1992 (apparently Microsoft tried to get it banned) because it mentioned stuff like Bill Gates not showering regularly, and drunk-bitching about IBM in a meeting with Lotus executives (which found its way to IBM). Should you read it? Well, if you have a deep interest in Silicon Valley history like I do, go for it. If you don’t, then strictly don’t bother, though if you do, you won’t be disappointed!

The Rise of Asian Paints (2024) – Anupam Gupta

Well-written chronicle of the birth and rise of Asian Paints, as well as its ‘first among equals’ cofounder Champaklal Choksey. From what i could make out basis the book, Asian Paints’s growth is a classic compounding play, benefitting from the steady growth of the Indian economy as well as the ’70s FERA diktats that kneecapped its foreign-owned rivals.

It ran a tight operational ship and took a set of bold decisions, such as investing in R&D / product development by hiring chemistry experts, bringing in professionals to run key aspects of the

business (first family business to hire from IIMs in a big way, investing in tech (first non IT co to invest in a computer in early 70s), going direct to retailers bypassing distibutors, investing in brand marketing etc.

Breaking the Mould (2023) – Raghuram Rajan & Rohit Lamba

A cautious, or even a mildly negative take on the Indian economy and the recent policy directions. In particular I enjoyed reading the authors’ take on why the PLI (production linked incentive) is an expensive mistake. Along with the analysis of recent policy missteps it also tries to lay out recommendations to set the economy on the right course.

India is Broken (2023) – Ashoka Mody

Good breezy read on India’s economic history since 1947 with a deep dive and discussion of its economic failings. Skewers both the Congress and the BJP. Much like ‘Breaking the Mould’, recommended if you like to read books written from a macroeconomic perspective on India.

Beyond Market Value (2019) – Annette Campbell-White

Interesting though ultimately a slightly disappointing read. It could have been so much more I felt this book, an autobiography by a venture capital investor and rare book collector. I was expecting an equal weightage to both topics, but sadly it is a bit weighted in favour of book collecting. As a female investment banker-turned venture investor, and as one of the few female VCs in her time, a detailed and comprehensive narrative of her career and investing experiences would have been fascinating to read. In fact we do get a few glimpses of this but they are too few and far between.There is far too much space given to books and book-collecting, and while there are some amusing anecdotes, sadly much of it is not as interesting as the venture part. Yes, your mileage may vary, depending on your interests. That said I have reasonable interest in both and yet, I felt the book collecting part overwhelmed the venture part, leading ultimately to a book that is not as intriguing as the cover and premise suggests. Still given the topic and the author’s candour, I felt this was worth an inclusion.