Finally wrapped up a slow read of Richer, Wiser, Happier by William Green. Enjoyable book taking a close look at the investing approaches of public market long-only investors such as Mohnish Pabrai, Joel Greenblatt, Howard Marks, Bill Miller, Nick & Zak of Nomad, Charlie Munger and a few lesser known (at least to me) ones such as Tom Gayner, Matthew McLennan, Laura Geritz, Joel Tillinghast etc.

Interesting how their philosophies converge around concentration, patience, truth-seeking etc. Much of this is well-known / found in writeups on other investors as well. Still what stood out to me is an approach for which I use the word subtraction (maybe a fancy word for focus!) – that is eschewing ‘riskier’ or ‘fragile’ investments to come up a shorter list of potential stocks that they track and enter when attractive.

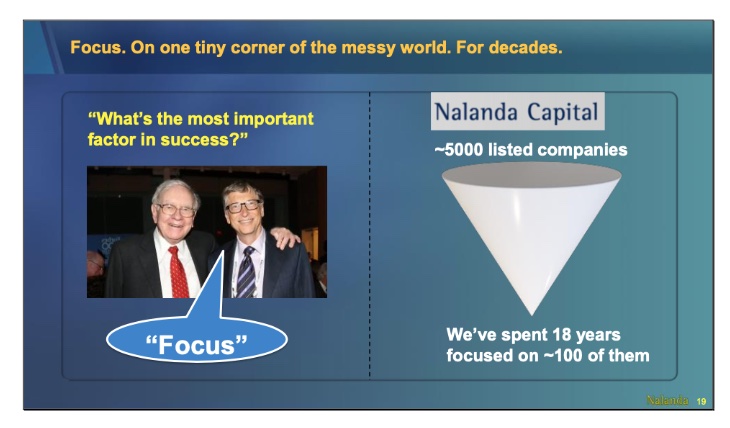

Pulak’s book also described Nalanda’s investment approach as centred around Subtraction. They track ~100 stocks which have passed all their filters, and track them for markets like this when the price becomes attractive enough to load up. Here is an image from a public presentation by Anand Sridharan of Nalanda Capital.

From the book, some relevant excerpts:

– “What made Jean-Marie Eveillard an enduring giant of global investing was that he avoided losses by repeatedly escaping the deadliest dangers in his path. It was a triumph of omission, not commission. Looking back on his career at SoGen and First Eagle, he says, “To the extent that we’ve been successful over the decades, it’s due mostly to what we did not own. We owned no Japanese stocks in the late eighties. We owned no tech in the late nineties. And we didn’t own any financial stocks to speak of between 2000 and 2008.” His ability to sidestep those three disasters over three decades made all the difference between failure and success.”

– “Matthew McLennan begins by chiseling away anything that looks faddish, including countries and sectors that have attracted “indiscriminate” flows of capital. That habit protected his shareholders when the beloved BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) stumbled and Brazil blew up. He also avoids countries with political systems that don’t respect property rights. Likewise, McLennan chips away any company that he believes would add fragility to his portfolio. For example, he avoids business models that are particularly vulnerable to technological change. He’s equally averse to companies with opaque balance sheets, too much leverage, or imprudent management that is “too expeditionary.” That protected him from time bombs such as Enron, Fannie Mae, and all of the banks that imploded during the financial crisis. “

– “During an interview in Boston, I asked Joel Tillinghast to explain his winning strategy. He responded by listing everything that he avoids. For example, he steers clear of development-stage biotech stocks, knowing that they’re likely to bring out the worst in him. He can’t make a valid earnings forecast because their “future is so murky. So I’m not going to do biotech stocks.””

*

How does the above contrast with venture? My colleague Rohit picked up the line describing Jean-Marie Eveillard’s approach as a triumph of omission not comission, and asked me about the contrast with venture. It is true that errors of omission are far costlier in venture than in the public markets. Still, venture investors also use past patterns, and filters to parse through deal flow per their field of play / investments. Without having some principles of subtraction or focus (however you describe it), you will struggle to review all the inbounds you get, and struggle from cognitive overload. The best venture investors do subtract, and have very evolved antennae to pick up signals / are exceptionally good at pattern matching.

*

If you liked reading the above excerpts then I have 50+ pages of highlights excerpted from the ebook, and organised by various investor and investment characteristics. Enjoy!