[This was written in late’21, and I had posted it as a Notion page. Now consolidating all of these reviews posted elsewhere into this site.]

Published 2015; 320 pages. Read Nov’21.

The Wright Brothers by David McCullough was easily amongst top 2-3 books I read in 2021. It is a terrific portrait of two obsessed inventors from a small town in USA who were able to achieve what many well-resourced and seemingly better-placed peers of theirs couldn’t. It is also a wonderful illustration of the inventive process, as it takes the reader through how the brothers systematically attacked the barriers in the way of flight. The book is an easy breezy read as well, and is highly recommended.

I found the book fascinating from multiple perspectives. One of course, is that the book covers the process of invention, and how the brothers overcome various barriers. The second is that the book provides the historical and societal context in which the invention was made, not to mention the institutional underpinning required to make the invention happen. Here is a look at these and other themes I found interesting from the book.

Institutions matter

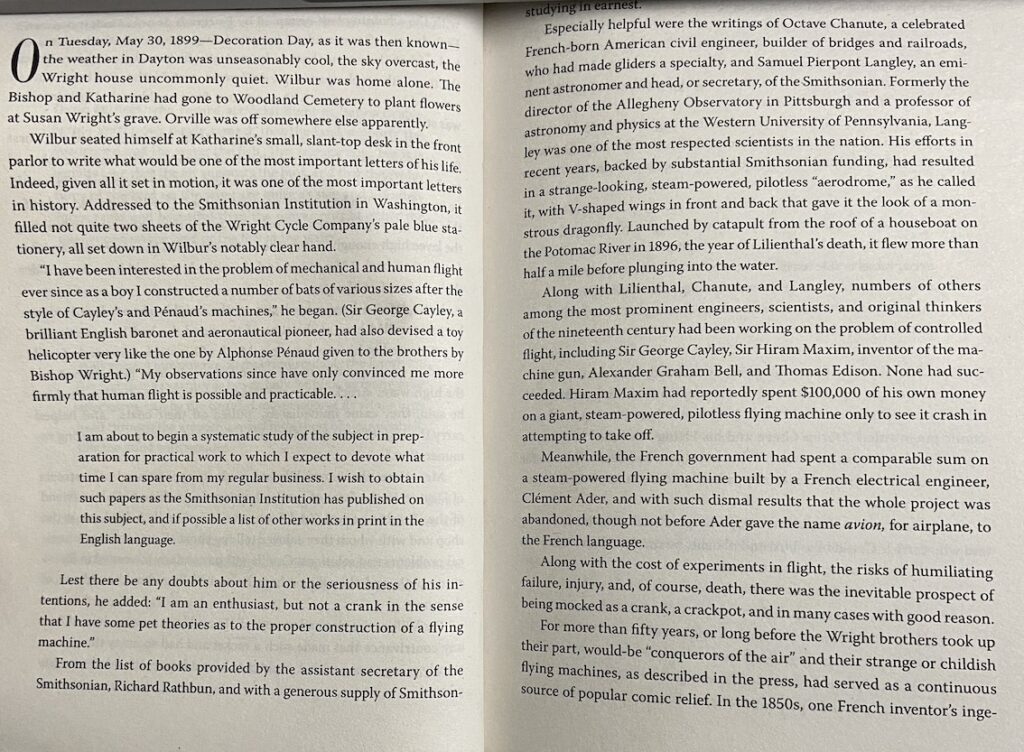

Let us take institutional underpinning. The late 19th century U.S. was blessed to have well-functioning public and public-private institutions like the U.S. Weather Bureau and the Smithsonian Institution. Wilbur Wright wrote to the Smithsonian to get books and papers on aviation, which were not easily availably in his small midwestern town. He wrote to the Weather Bureau to get data on wind speeds, to select the right geography for their experiments. In both cases, he got prompt helpful responses. Not only did they have what he wanted, they were helpful as well. It is not entirely accidental that the first manned and controlled flight was made in the United States. They had the economic, cultural and social infrastructure to support and sustain such experimentation.

Pgs 32-33 of The Wright Brothers. Wilbur Wright writes to Smithsonian and gets back a recommended set of readings and papers on aviation.

Pgs 40-41. Wilbur Wright writes to the U.S. Weather Bureau in Washington, who provides him with wind velocity data across the nation (over 100 bureaus!). He then writes to the Kitty Hawk bureau, who too responds. Not just that, the former postmaster reaches out with details too. This is a high trust nation, and one that tolerates inventors and eccentrics.

A systematic four-step process to controlled, manned flight

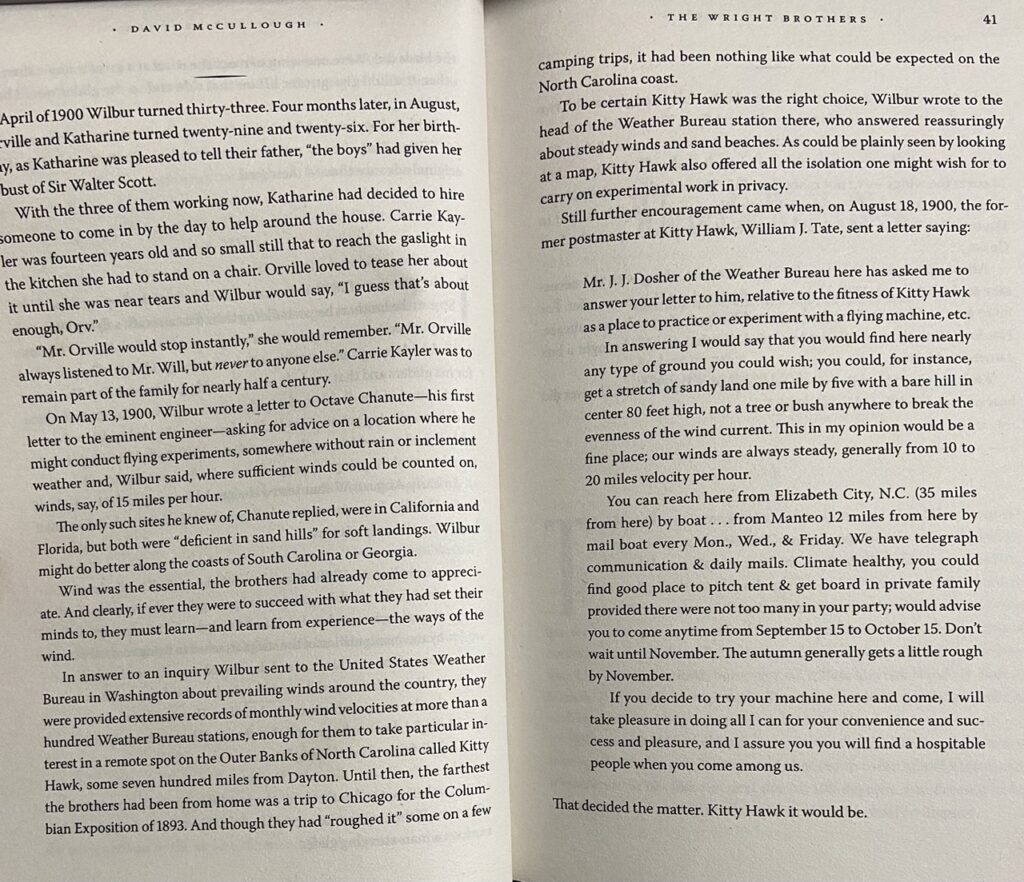

The Brothers started exploring flight in the summer of 1899, after they received a set of papers and a list of readings from the Smithsonian. After determining that Kitty Hawk was the best place to experiment with a flying machine – both due to wind speeds which aided flight, as well as the presence of soft land, should the machine crash – they made four sorties to Kitty Hawk, one every year from 1900 to 1903, to test out their continuously improving designs and making systematic progress towards their goal.

Here is a tabular progress chart.

| Timeline | Description of machine | Wingspan |

| 1899 Summer, Dayton OH | Flying kite made out of split bamboo and paper | 5 ft. Biplane, with double wings, one over another. |

| 1900 October, Kitty Hawk NC (Wilbur was there from September) | Glider. To both fly as a kite, and carry a man. | 18 ft (later reduced to 17 ft) x 5 ft. Two wings, one above another. About 50lb weight. |

| 1901 July – August | Larger glider. Encountered poor lift, despite them using the existing calculations for lift. | 22 ft with double wings, one over another. |

| 1901 October – December | Wind tunnel (6 ft x 16 inch square) experiments to get correct lift and drag coefficients. | |

| 1902 September – October | Larger glider with new design and material basis data from wind tunnel experiments. Huge success. | 32 ft x 5 ft, double wings, one above another. |

| 1903 September – December | 12hp motor attached to a larger ‘glider’. | 40 ft; about 600 pounds weight |

The 1900 Glider, via Wikipedia

The 1901 Glider, via Wikipedia

The 1902 Glider, via Wikipedia

The 1903 Flyer (or Flyer I), via Wikipedia; achieved max distance of 852 ft on a flight.

It is important to note that during these 4 years, the Brothers kept their bicycle business going, using the earnings from the bicycle business to finance their aviation experiments. They had to be careful with how much time they could allocate to these experiments given that each day away from the bicycle business in Dayton, Ohio, was costing them earnings!

After Kitty Hawk

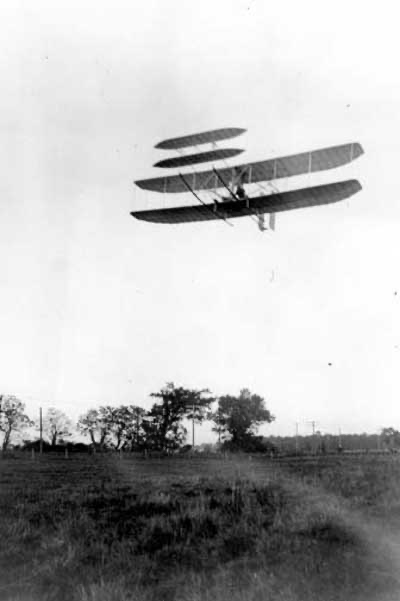

After achieving success with the first manned flight on 17 December 1903, the Brothers never went back to Kitty Hawk till 1908. In the interim, they instead kept improving their ‘aircraft’ or Flyers, testing them in a cow pasture called Huffman Prairie, close to their home. The advantage of operating close to home was that they could test or fly more frequently.

Flyer II was flown from May – November 1904. Picture via Wikipedia.

Flyer II saw flights of up to 3 miles (in 4 circles) exceeding 5 mins, and went as high as 25ft up in the air.

Flyer III (25hp motor), and the first ‘practical airplane’ in history; flown from June – October 1905.

Flyer III achieved distances of 24 miles in 38 minutes (5 October 1905). Heights of 100 feet in the air was achieved.

Ignored by the Press

I found it interesting that there was very little media / newspaper interest in the Brothers. This excerpt is telling.

It is interesting that the first person to break the story of the Brothers’ successful flights was Amos Root, a 64-year old ‘technology’ enthusiast, who published his account of a 20 September 1904 flight that Wilbur Wright made, in his company’s beekeepers journal ‘Gleanings in Bee Culture’, in January 1905. Root even sent a copy of his publication to Scientific American, encouraging them to reprint at no charge. Scientific American not only ignored this, but kept continuing to doubt the Brothers’ achievements in a subsequent issue.

Picture of Amos Root, via Wikipedia.

The original ‘Mother of all Demos’

On 8 Aug 1908, in Le Mans, in France, Wilbur Wright flew two miles in two minutes before a large crowd. The successful flight before members of the French army – who were keen to buy aircrafts from the brothers, as well as get their pilots trained – set off a frenzy of coverage and celebrations.

Picture source.

In September that year, Orville Wright made a series of successful flights at Fort Myer, near Washington, D.C., before the U.S. Army leadership as well as the government establishment. In one of those flights, the plane crashed, killing his fellow rider, and injuring Orville Wright (though he made a speedy recovery).

Pace of Change

The passage below is a great example of how fast innovation can spread. Until December 1903, no one has made a manned controlled flight. Barely six years later, there were flying competitions!

Overall, a terrific read. Highly recommended for anyone interested in aviation, or the history of technology; actually just about anyone!