I recently met the founders of a quasi-dating app enabling friend discovery via meeting strangers at events. We passed on them, primarily because while we could see that it had the potential to ‘take off’ in metros, or at least the affluent parts of our metros, we couldn’t see how it would work in India2 i.e., the non-english speaking less affluent India in Tier 2/3 cities, and thus expand to become a mass product. We asked: would an app that enabled interaction with strangers work in small town India where almost everyone seems to know everyone (at least in the upper social strata)? Would a revenue model that aimed to take a cut of the revenue that venues earned, work in smaller cities, where they were possibly only a handful of venues which didn’t need marketing?

This is broadly true of almost all dating apps, which are native to India1, the English-speaking world that people like us inhabit in metros. In fact, they inhabit an even rarer universe that I like to call India1 Alpha, the world of cold press coffee and organic food, of Netflix and Apple devices, of Nicobar dresses and IB schools. My young colleague Sanchita Bamnote refers to the slew of startups catering to this market, the Creds, the Raw Presserys and MamaEarths as ‘Avocado Startups’, after the fruit that symbolizes luxury.

Avocado startups and the Starbucks rule

Now, luxury market segments exist in most emerging markets. Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Philippines all have their super rich and therefore a service economy that caters to their needs. But what distinguishes India is the sheer size of the plutocratic segment, pretty much the size of some countries in Central Europe. India1 at ~110m population, and even its subset India1 Alpha at ~10m, are large markets, which can sustain the creation and growth of indigenous brands native to this category.

These native brands, be it those of India1 such as Zomato, Oyo, Ola or even the more rarified avocado startups such as Raw Pressery, Epigamia, TeaBox catering to India1 Alpha, find it far easier to expand abroad than to the rest of India. I like to think of India1 as an agglomeration of all of the pockets around a FabIndia store, ringfenced within this albeit arbitrary limit. (Last count there were about 266 FabIndia stores including in places such as Pollachi and Haldwani; so this isn’t the most ideal criterion, but it should do roughly). Similarly I look at the seven Starbucks Cities in India as the limit of India1 Alpha. Beyond these seven cities and their limits, there isn’t much for a market for avocado startups and product market fit (PMF) is hard to come by.

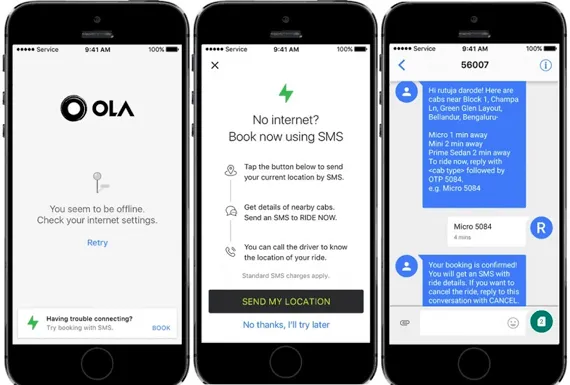

India can be understood as a four-tier consumer stack

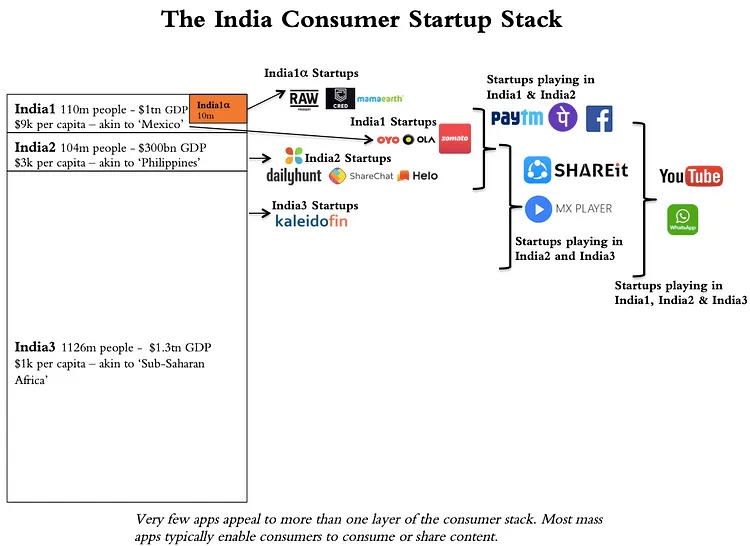

A good way to see India is thus as a four-tier market, with each tier being able to support a set of native startups, which struggle to expand beyond their market. Each market has its distinct audience profile, pricing sensitivity, cultural attributes and competitive dynamics. Product market fit (PMF hereafter) in one market doesn’t automatically translate to the possibility of a fit in another. If anything product market fit in one market makes it tougher to succeed in another. There are just a handful of products, typically with universal uses cases (Youtube, Whatsapp, Flipkart etc) that have succeeded in both India1 and India2.

Here is a graphic that illustrates the India consumer stack and the startups that are native to each tier.

Let us look at the prominent startups across each tier of the stack and what is driving their launch.

How do you move across the layers of a stack?

Most startups start in India1 and then attempt to move into India2. Few succeed. For one, there may not be a natural usecase such as for Uber in a small town like Satna. Either there may not be enough of a need for ondemand services in Satna, or if there is, the friction to hire a rental taxi may be much lower than in a metro, i.e., There is either no market, or there is no need for the product that you are pitching to solve the consumer’s need in that market. There may be other (existing) ways for the ‘job to be done’ that are as good if not better. Thus the ground rule: PMF in India2 is possible only when there is a large enough market for what your product is trying to solve for, and your product is the best way to meet the market’s need.

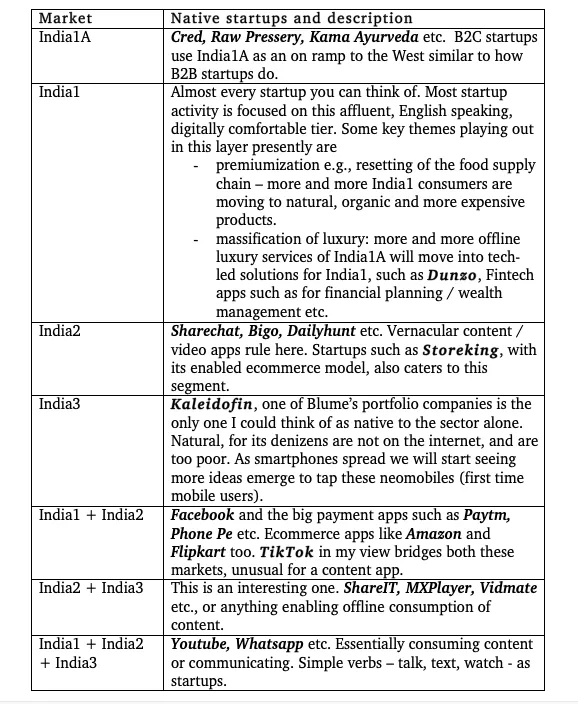

Then there is the question of language. Apps designed for India1 assume good English prowess and a native understanding of UI (e.g., what the shopping cart and the magnifying glass icon mean). The same doesn’t necessarily hold. Amazon found that many India2 users mistook the magnifying glass or the search icon for a table tennis racquet! The predominantly English interface also creates friction reducing easy adoption. (I refer to this, in an article I wrote last year, as the English tax).

Still, there have been some success stories — Paytm, Flipkart, TikTok, Facebook have all moved from India1 to India2. In the case of Tiktok, it didn’t move as much as achieved PMF in both markets simultaneously. How have these startups managed to transition from India1 to India2?

For one, it helps if your product is catering to a universal need, such as payments, or connecting to another person / staying in touch, i.e., the market is large enough. Not all products however are solving for a universal need, or have universal usecases such as payment and ecommerce apps which imply a large market, so it is only a small set of India1 apps with broad usecases that can theoretically break into India2.

But it is not just the market that has to be large. Even apps such as ecommerce apps, with their universal usecase have struggled to expand into India2. Success has come only when they have been able to make product adjustments to reduce friction, and be the best way to get the job done. Now, what are these product adjustments?

Getting your product to fit the India2 market

Let me list some popular approaches.

(1) Moving some elements of the product offline, such as what Amazon has done with its Storeking partnership, or what Flipkart did with Cash on Delivery

For ecommerce, transacting especially paying is the highest friction part and if you could move it out of online and get it solved offline, such as with Storeking (enabled ecommerce) or Cash on Delivery, despite the relatively higher cost, it made sense, for it spiked conversions up dramatically.

This is a reasonably universal rule for driving consumption and usage of your app or startup service in India2. Move parts of your app offline, typically those with relative higher friction for India2 consumers, such as customer acquisition, or conversion (payment). Byju’s / Toppr does this well, customer acquisition and conversion are in person, but the delivery is online.

(2) Using local language instead of English and modifying the UI to suit local tastes. This is obvious so I wont say more, except that I am still looking for more examples of India1 apps that have modified their app for India2

Here is one on how Amazon modified its app for India2, via WSJ.

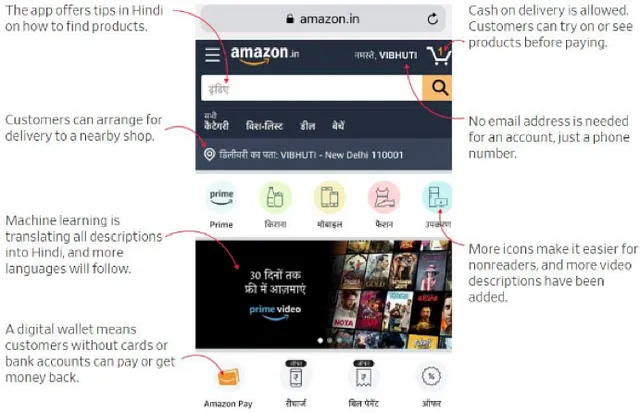

(3) Enabling apps to work offline.

Ola allows you to book a cab offline, and Youtube in India allows you to download videos for watching later. This makes sense in a market where internet is spotty, and wifi is nonexistent beyond metros.

(4) Making apps lite by reducing feature sets, to help spur usage.

Android Go’s launch spurred a host of lite apps including those from Facebook, Uber, Youtube etc. The reduced feature set creates a MVP (Minimum Viable Product) that is easier and cheaper to download, and relative simpler to use. At least that is the idea.

Some times, even apps that find successful PMF need to reduce or downgrade their features etc. Whatsapp is a good example in this regard.

It found PMF in India1 and India2 quite easily but as it reached into India3, it started having challenges with how it was used and perceived by neomobiles (my coinage for new mobile users). Rumours spread through whatsapp have resulted in mobs killing innocent people. As a result of these incidents, and also in order to stop whatsapp from being weaponized for toxic political campaigns, it had to downgrade its product by reducing the number of people you could broadcast a message to, and thereby modifying down its featureset. Unfortunately these changes impact everyone including its India1 users.

Still, it only had to change a feature or two, to ensure the product remained relevant for India3. Clearly the more universal a startup you are, the less you have to change. Perhaps a feature or two needs to change, such as what Whatsapp did or Youtube, which introduced the offline save option. Others have to change their product, and the ones with the least universal usecase change their entire business model if they have to cater to India2 or India3.

The curious case of Tiktok

Tiktok from Bytedance is particularly fascinating for it is simultaneously finding PMF in India1 and India2. I don’t think there is any other product similar to it that has found easy acceptance in these two distinct markets. Racy content helps but more than that it is also content that strikes a chord with India2, thanks to a lot of content creators encouraged (sponsored) to come aboard the platform. In addition Tiktok has also enabled content creation as per formats (challenges) that make it easier to create and consume content, not to mention a superior content recommendation algorithm.

How PMF challenges are influencing the startup ecosystem

Recently Mihir Dalal of Mint newspaper, wrote a piece titled “Smaller than you think: India’s online paradox” where he covered how ex-founders such as Kunal Shah, Satyen Kothari, Ashish Kashyap were launching niche startups aimed largely at India1A or India1.

In fact, Mihir Dalal’s piece got its emphasis slightly wrong. For every ex-founder launching an India1A startup there is an ex-founder launching a massmarket India2 focussed startup too. Aprameya Radhakrishnan’s Vokal and Sumit Jain’s OpenTalk are two examples. What is happening is not so much everyone launching a niche startup as much as a recognition by founders that it is getting harder and harder to launch a universal product for the Indian market, one that can appeal to India1 and India2 and achieve PMF in both. Hence startups are cleaving into clean India1A, India1 or India2 models.

Seasoned entrepreneurs launching these focused startups have a problem of plenty, for not only are they finding it easier and quicker to start tech-led businesses, they are also finding access to capital easier to come by. More and more money is entering the VC industry and once in, chases good founders relentlessly. As a result, founders now have smaller defined TAMs (Total Addressable Markets) and greater funds to deploy. The result is that well-funded startups are doing one or more of the following: expanding abroad, going full stack or moving into adjacencies.

I remarked earlier on how India1 Alpha startups such as Raw Pressery, Epigamia are expanding abroad. Not just them, even India1 startup Urban Clap, with its far larger TAM has expanded abroad. I find it particularly interesting that even as a wave of consumer startups focused on India1 Alpha emerge, all treating India as an onramp to international markets, on the B2B side, where such international expansion has been historically very common, we are seeing a reverse trend i.e., the emergence of India-focussed B2B startups (Udaan, Moglix are well-known but there are more coming).

Startups that chose not to go abroad or have excess funds left over can use the funds to go full stack (Oyo runs hotels now, and UrbanClap manufactures beauty products) or expand into adjacencies (Ola into food delivery, Swiggy into microdelivery of milk, grocery or even ondemand grocery orders). For startups focused on solving for specific use cases, the presence of well-funded competitors expanding into their adjacencies is a challenge, but it is something they will have to live with for a while.

Summing Up

India1 where much of the venture capital and startup attention is directed is an economy that is the size of a Mexico. But unlike a Mexico it attracts disproportionately larger startup capital and sustains a larger and more innovative pool of startups. But these startups largely struggle to cross over into neighbouring segments such as India2 and India3. There are however exceptions, and we looked at how some of these few firms that play in all of these segments had to adapt themselves and their products.

Increasingly startups are today picking markets to play in, and are under no illusions that they can become universal products catering to India1, India2 and India3. Capital however continues to chase them like they are universal products. As a result, we are beginning to see these players expand abroad, go full stack or move into adjacencies.