In publishing, interleaved books are those sold with blank pages inserted between printed pages so as to facilitate note-taking. This was a common practice in the 16th and 17th century, but has disappeared now. Thus my term ‘Interleavings’ for my notes and thoughts on the digital texts I enjoyed reading.

Here are my interleavings from the recent past.

Podcasts

1/ The four personas of B2B software sales

Link to podcast. Link to excerpts from the podcast episode I found interesting.

Cyberstarts is one of the most successful venture capital firms in the world. They do only cybersecurity software investments, and are based in Israel. Their first fund resulted in a 40x return(!) thanks to stakes in firms such as Wiz, Island Security, Fireblocks etc., and across five funds and $700m invested, the portfolio value is $45b, half of the valuations of private cybersecurity companies!

In the episode, Gili talks about the Cyberstarts fund philosophy, and the Sunrise program they use to figure out what problems the founders should go after. The Cyberstarts methodology works differently from traditional venture. Instead of backing teams with existing tech / product going after large markets (the typical way), they identify founders (typically from Israel’s elite cyberwarfare-focused Unit 8200) who spend time talking to CISOs (Chief Information Security Officers) to figure out problems they have and which they can solve for, and only then do they start building. This is the famed Sunrise program.

There has been some controversy about the Sunrise program given that many of the CISOs they interview get carry in Cyberstarts, and the carry can increase if you also purchase the products of Cyberstarts’ portfolio companies. Hmmm. News is that this payments program is now suspended. If we ignore the payments part, then the methodology of understand what the market wants before building is a useful one to keep in mind (compare with Jen Abel’s perspectives below on market-first startups hitting PMF faster than product-first startups, though the latter have a far bigger upside).

The other interesting perspective was Gili’s framework of the four personas – the one with the pain, the one with the budget to pay for a solution for the pain, the one with the authority to approve it, and finally the one who will use the product. The more these four converge into one persona, the faster the chances of PMF and success for the startup. Really insightful.

“Gili Raanan: And then I learned a very important lesson about the four customer profiles. When you sell a product, you’re going to face four personas. The person that has the pain point, the person who has the budget to pay for a solution to solve that, the person that has the authority to decide on the product or solution, and the fourth person is the one who would actually use the product. Now, as a startup, if those four personas map into a single person in real life, that’s a mega hit.

And that was the case of Wiz. If those four personas are mapped into four real people, there’s one real person that has the problem, one real person that has the budget, one real person that has the authority, and a fourth person that actually uses the product. Don’t do that. Go and pivot.

And if you map into two people, that would be a very nice company. If you’re mapped into three people, that’s borderline. You may or may not want to pursue that. So for Wiz, it was a single person. It was the CISO. The CISO, the Chief Information Security Officer, had the problem and the authority to decide on a cloud security solution. They obviously had the budget and, most importantly, they had the AWS credentials that enabled them to deploy the product. So Wiz was able to do something very unique just because all those four Personas mapped into one real-life person.”

2/ Puzzles vs mysteries

Link to podcast. Link to excerpts from the podcast episode I found interesting.

Serious venture nerds will find bits and pieces of this episode featuring Nabeel Hyatt, GP at Spark Capital (Twitter, Antropic, Discord etc.,) interesting, but on the whole, there is nothing exceptional here. Still what stood out:

- Nabeel’s framework about the three types or lenses of AI startups (adaptation, evolution, revolution)

- his observation about venture moving from the puzzles phase to the mystery phase (inspired by US intelligence operative Gregory Treverton’s maxim)

- Nabeel’s point about misalignment of incentives at the Principal / Junior GP level, where they are driven to deploy fast and get markups.

- A quote that stood out: ”It is hard to optimise for performance when your competitor is optimising for deployment.”

Nabeel: “Greg Treverton uses this phrase of puzzles versus mysteries, which is just like, puzzles are this thing that you can like, use that raw horsepower to solve, and mysteries are, you have to go on the journey. In many ways, like the B2B SaaS blow up of that era was all about like the industrialization of venture capital. It was all about figuring out all of the puzzles needed to hire 100 associates to do all of the work, to figure out exactly the right SaaS metrics, and then grind it all out. And no one has any idea what a model is even going to do in a week. So I don’t know how that isn’t a mystery. And so I think you have to build a firm with that set of talent.”

I would say the early stages of venture capital, the like real early stages of venture capital, if we’re thinking about the beginning of Sequoia and so on, like that was all mysteries, man. Like that wasn’t puzzles. And so I think the truth is it may sound incredibly old school, but it’s going back to the way things were really done before. It is an artisanal business. There’s a reason it’s an artisanal business.”

3/ “PMF is faster when you go market first, and not product first”

Link to podcast. Link to excerpts from the podcast episode I found interesting.

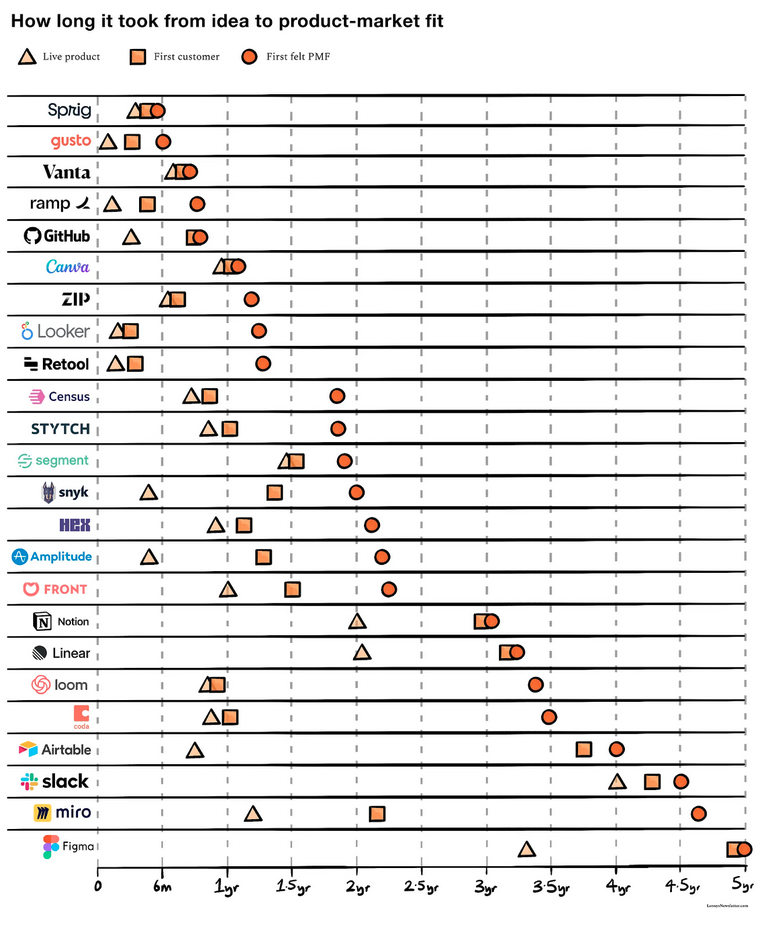

I thought this podcast episode where Jen Abel of GTM consulting firm Jjellyfish covers the nuances of founder-led sales was really good. Very very relevant for early stage B2B founders. One point that stood out for me was her pov on how going market-first (understanding the pain points of a market first and then building the product) can take you to PMF (product-market fit) faster vs going product-first, where your leverage the state of the art in tech to build a cool product, and search for a market large enough. That said going product-first offers a more unbounded upside (and downside). Very interesting, and the reason why the Sunrise programme (see the podcast episode on Gili Raanan of Cyberstarts referred to above) succeeds becomes apparent now.

“Jen Abel, GTM Consulting Co Jjellyfish: Remember that amazing chart you drew where it talked about the length of time it took for product market fit. If you look at the top section where the time to product market fit is consolidated, and you go all the way down to the airtables and the figmas, which a long time to get to product market fit. If you think about the earlier ones, which were, it was like GitHub that had product market fit pretty quickly, then Vanta.

There’s this thing in my head and I haven’t fully validated it but I’m going to share it with you, which is did they start with the market problem first and then build the product? Because they knew who their market was right off the bat. Versus an airtable and a figma that I think started with a technical insight and then were trying to find their market.

Lenny: I think that’s absolutely right. Vanta, the way they approached it, Christina, she was searching for a pain. She was obsessed with talking to everybody about a pain that they needed solved, and then she just built it in spreadsheets. So she started with the market very much so.

Jen: And I think product market fit when you start with the market first, it’s accelerated. But I will say this, I think that it’s also capped on the upside. Because you’re starting with the market versus the airtable and the figma, which started with the technical insight and has uncapped upside. But one is certainly riskier than the other.

Starting with a product is a hell of a lot riskier. And this is where I come back to so many people will say, how did you get funding and not know who your market is? And it’s like, because if they do find it, that’s a really, really, really big win. Versus I think if you start with the market first, you could potentially get a good win but is it more capped?”

4/ Sometimes the most valuable writing a writer can do is to sign your name repeatedly!

Link to podcast. Link to excerpts from the podcast episode I found interesting.

I haven’t read Brandon Sanderson, and very unlikely to but this was a fascinating chat all the same. What stayed with me

- the two types of (fantasy) fiction writers – gardeners who don’t have every plot element defined prior to writing, and architects, who do (originally suggested by George R R Martin)

- his view of plot as progress (mysteries are where plot progresses in terms of revealing of information); aspiring fiction writers should check out his course lectures

- pros / experienced writers throw out chapters a lot, while amateurs tend not to

- a fascinating passage / discussion on the value of his time, and how an hour spent signing copies makes him $250k and how he has had to set boundaries on things that take him away from writing, like talks.

Tim Ferriss: — because you end up placing so high a per hour value on your time, that every squandered minute is like having a pound of flesh taken and you can drive yourself insane.

Brandon Sanderson: Yeah. I wind in that because if I sign my name, that’s $250 because of the leatherbound. But I don’t want to spend my life signing my name, I want to write the books. But the most money I can earn per hour, I can sign 1,000 of those in an hour and that’s 250 each, which is just an unreal — if you think about that, that’s like — yeah. That’s —

Tim Ferriss: That’s bananas.

Brandon Sanderson: That is bananas. My normal writing time, I can put a different dollar amount. It depends on what I’m writing —

Tim Ferriss: Did you ever get pulled — because it happened to me with speaking engagements, different thing. But did you get pulled away from the creative work or the actual wordsmithing at any point or were you able to hold the line?

Brandon Sanderson: So I was able to hold the line, but barely. At one point, I started to get popular enough that people wanted me on a speaking tour, right? And so, I put a dollar amount on it. I’m like, “Well, at that point, a day of writing,” and it’d take me two days, “a day of writing is 25 grand.” So two days, 50 grand. And we put it up there. Instantly, like 10 inquiries. And I’m like, “I don’t want to do that.”

5/ The metric that matters

Link to podcast. Link to excerpts from the podcast episode I found interesting.

There were three ideas or concepts that stood out for me from this episode. The first was on designing an organization or career or an investing strategy that plays to your particular strengths and how you like to spend your time. He gives the examples of Michael Dell, and Warren Buffett. Figure out your strengths and stay around that. The next is on incentive design, and how not to reward short-term / profitability metrics – good illustration of how profitability incentives encourage managers to cut brand spends (the long-term important but not today’s essential) and how that impacts the long-term sustainability of the brand. Finally, there is a wonderful passage on how there are only one-two or perhaps one metric that matters – in the case of Coca-Cola all that mattered was whether daily servings would grow globally. If you believed it did, you knew you could continue holding or topping up your investment.

Senra: “In business we often find that the winning system goes almost ridiculously far in maximizing and or minimizing one or few variables.” Sam Zell says the same thing. What they say about Sam is what Sam said about Jay Pritzker.

Jay Pritzker was his mentor when Sam was a very young man. I think he was still in his 20s when he met Pritzker. He said that Pritzker was the greatest financial mind of anybody he ever met. Sam would bring him a deal or they would talk about buying a business, and he’d say, “Okay, here’s a list of eight things or seven things that we need to worry about.” And Pritzker would respond, “Bullshit. That’s the one thing. There’s only one variable. And if you solve for that variable, the deal will work out.”

They’re talking about how if you went back in 1919, you could have bought a share of Coca-Cola for 40 bucks. And in between that time, it dropped by 50% multiple times. There was World War II, there were pandemics, there was the invention of the atomic bomb. And really the only important thing was how many servings of Coca-Cola were going to be served every day many years into the future. So you think about what is the most important factor. That’s what Jay Pritzker taught Sam Zell. That’s what Sam Zell taught other people.

And that’s what they’re saying here. Wars be damned. Economic or financial crisis be damned. If I’m buying the stock for the long term—and I forgot how long they may have been holding this, perhaps three decades—are they going to be serving more Coke on a daily basis in the future? All that mattered was by 1998 they were selling 1 billion servings a day. And Buffett makes the point here: “The person that can make people a little happier a billion times a day around the globe ought to make a few bucks doing it.”

“If you developed a view on any other subject in any other way that forestalled you on acting on that which is most important, the specific narrow view about the future of the company, you would have missed a great ride.”

6/ Focus on the one single thing

Link to podcast. Link to excerpts from the podcast episode I found interesting.

In the last Interleavings I had linked to an article on Neil Mehta, published in the Colossus Review. This is the companion podcast episode for the article. Covers much the same ground, and there isn’t anything dramatically new. Still I found it useful to be reminded of Neil Mehta / Greenoaks focus on identifying the 10-15 best founders that matter, building products offering ‘jaw-dropping customer experiences’, and overpreparing for their meetings, and getting answers to the question: “Are your best days ahead of you or behind you?”.

This below quote on Korean ecom co Coupang’s founder Bom Kim’s ability to focus on the single most important (SMIT) at the startup at the time, was very interesting to read. I like to use the term Herbie for the most important thing or chokepoint at a time in the startup’s or project’s life. I encountered the concept in a Mike Maples podcast, who got it via The Goal. In the book, The Goal by Eli Goldratt, Herbie was the fat kid setting the speed of the group trek. It was only by speeding Herbie that you could increase the speed of the group. Herbie is the rate limiting factor at that point in the startups’ life. Herbies change from time to time in a startup’s life – sometimes it is top of funnel, sometimes it is fundraising, sometimes it is retention. Getting to PMF and eventual success is nothing but the founder sequentially removing these SMITs / Herbies along the startup’s journey.

“Neil: It starts with focus. Bom (Kim of Coupang) had this unique ability early on to identify what was the most important thing in the company and focus all his time on that, at the exclusion of everything else. It wouldn’t be unusual if you looked at Bom’s calendar on a Sunday night, everything the next week, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, it would just be blocked out with one single thing he was trying to accomplish.

If it was negotiating cost of goods sold in the diapers division in mid-2014, there’d just be two weeks locked out to just do that for six hours a day, five days a week. And he would just assemble a team and go deep on that and let everything else burn if needed.

That kind of focus is just extremely unusual. People like to say they’re focused. They don’t really understand what focus means. Focus means saying no to everything else, everything else, at the cost of doing what the single most important thing is. There’s two parts to that. It’s the ability to prioritize what is most important. You have to practice it to be able to intuitively grok what is most valuable and most important.

And then the ability to maniacally do that at the cost of everything else is an intestinal fortitude that just not a lot of people have. “

7/ “Make something that people want. But it can’t be all people. It can’t be everybody.”

Link to podcast. Link to excerpts from the podcast episode I found interesting.

“But to focus on the segment of the somewhat disappointed people, they kind of love your product, but something, and I would wager something small, is holding them back. So you then divide them into two camps, the camp for whom the main benefit of your product resonates and the camp for whom it doesn’t. And what do I mean by that?

Lots here to chew on in this podcast episode, though the highlight was Rahul’s algorithmic or iterative approach to work towards PMF or Product Market Fit. That said, strictly speaking, in my PMF framework, it is actually PPF or Product to Problem Fit he is iterating towards. The other interesting points were his framework on market widening vs solution deepening, and how startups move from one to the other at different times, how manual onboarding helped Superhuman, and how to set pricing for software (or any other product). Really good.

Well, you go back to the people who really love your product and you basically ask them why. What is it about my products that you really love? In the early days of Superhuman, it would have been speed and keyboard shortcuts and the overall design aesthetic as well as the time that we were saving you.

You then go back to the somewhat disappointed users. And in the superhuman example, I would simply ask, wait, do you like superhuman because of its speed or for something else? And if it’s something else, well, and this is hard to do, but politely disregard those people and their feedback.

Because even if you built everything that they asked for, they’re still pulling you in a different direction. And the thing that they like the most from your product isn’t actually what the people who en masse love it the most for is. So you have then articulated the sub-segment of the sub-segment that it makes sense to pay attention to. “

Articles

8/ You are as good as your next deal

Link to article.

Sajith: I loved this passage from the Colossus Review profile of Matt Huang and his crypto venture Paradigm. It captures the typical mindset of the elite VC, obsessed with missing out on the next big venture investment even as s/he quietly notes / celebrates the last success.

At Sequoia, Huang found what he calls “the highest-standards place I’ve ever experienced.” When Facebook acquired WhatsApp for $19 billion on his second day, partners gathered briefly in the lobby. Champagne was poured but left untouched. Within five minutes, everyone had returned to work. Eleven-figure exits faded into the shadows of the firm’s legendary portfolio that includes trillion-dollar businesses like Apple, Google, and Nvidia. The culture demanded excellence in ways that elevated his already considerable ambition.

9/ A fishy tale

Link to article.

Riveting story of how the Indonesia aquaculture startup eFishery’s founder & CEO Gibran Huzaifa inflated his company’s revenues over a six year period, raising $300m+ but finally getting caught out. Its investors thought the revenues were $857m in the first nine months of 2024, but it was actually $172m. Huzaifa cooked the books successfully over a long period of time, but finally it became hard to maintain. That said, he doesn’t come across as a villainous figure as much as someone caught up in events that went out of control. All of us VCs have nightmares about scenarios like this. There is, truthfully, no way of knowing what happens inside a company, short of doing surprise audits, which corrodes the trust battery you have with founders. The best you can do is to avoid putting intense pressure on the founder to keep growing, and to let the founder know that it is not the end of the world if things don’t work out. While that isn’t what led to Huzaifa’s actions here, a key reason (though not the only one) for these frauds are spurred by the founder trying to keep the show going, lest they fall out of favour with investors.