This is over 20k words long! Feel free to print or download to your Remarkable / Daylight / Kindle Scribe / iPad for easier reading.

About this essay: This is the second chapter of a book I am writing on Product Market Fit or PMF (The first chapter is here). This chapter, The Pick, is about how to pick or select your startup idea / problem to go after. I argue that if the pick is done well, it can improve your chances of achieving Product Market Fit (PMF) disproportionately. This chapter thus covers the importance of the pick, the four routes to arriving at the pick (pain, personal experience, prospecting, opportunism), the criteria to evaluate the effectiveness of the pick (why this?, why now, and, why you?), and the two phases of getting to the pick (problem discovery, problem validation). In addition it will cover how to pick your cofounder(s) too. Do note that this chapter is not about how to get the best idea or indeed how to brainstorm, though there are references to how different startups have approached it, and some recommended best practices. It is more about the inter-relation between the pick and PMF, and how to pick a problem / space so as to set your startup for eventual PMF and success.

2A/ Understanding ‘The Pick’

2A.1/ ‘The Pick’ has a disproportionate influence on PMF

I stole the title for this chapter from the above tweet thread by Josh Kopelman, co-founder of the storied venture capital firm First Round Capital (early investors in Uber, Square, Notion etc.). It is a topic that is dear to his heart and one that he has repeated on several occasions. It is one that resonates with me too given my last six years in venture investing, and seeing the importance of how picking the right problem space can confer your startup with an unfair advantage. Hence I wrote ‘The Pick’, covering the first step of the startup journey, i.e., how to select the right problem to go after. I argue that if the pick is done well, it can improve your chances of achieving Product Market Fit (PMF hereonwards) disproportionately. Conversely, getting the pick wrong makes it harder for you to achieve PMF, and you will need to throw more resources including time, energy, and capital, to work towards PMF. Thus, the pick has a disproportionate weightage on PMF potential.

2A.2/ Where you play, or the pick, is more important than how you play

The pick’s importance is validated by founders who have struggled with the consequences of a bad pick. Ayokunle Omojola, founder of the failed in-app messaging startup Hipmob says: “When I think back to my last company … we picked a problem to tackle that we found really technically interesting. We cranked for years and worked so hard and it just didn’t matter. The lesson I took from it was that we had put so much effort into the actual work, and had not put nearly enough effort into choosing what to work on. That was a much bigger determinant to our outcome — we hadn’t chosen a large enough market. If you pick a big domain that’s rich with opportunity, it of course matters how hard you work, but you also get so much more leverage.” Angel investor Romeen Sheth puts it succinctly in his tweet.

Picking the space also has significant influence and impact on downstream actions or their efficacy. Todd Jackson, presently investor at First Round Capital, and previously a failed founder, shares: “…it’s the pick that determines the constraints and the boundaries of where you’re going to be working for the next, hopefully, 10 years of your life”. There are three important points that emerge from these honest admissions:

- the nature of the market or problem space matters as much as the effort expended working on the problem

- the pick sets constraints or boundaries on what you will be working on for a long time to come

- that once you have picked the problem space / market to work on, it is not easy to change it.

Thus, market or problem space selection is a one-way door, and because the market or problem space exerts significant influence on your eventual success, picking is easily the highest leverage action a founder can take early in their startup journey.

There is also another reason why the pick matters overwhelmingly for the founder. They have at best, 3, maybe 4 picks in their life.

2A.3/ Founders do far fewer picks than a VC; hence don’t rush the pick!

As an early stage VC, I invest in 2-3 companies a year, and 8-9 across a fund. So long as 2-3 investments (of the 8-9 I lead in every fund) succeed, I am good. What about the remaining 6-7 that don’t succeed? Well, I hope the 2-3 that succeed, do so well that they cover up for the 6-7 that don’t succeed. It turns out that this is a feature, not a bug, of the venture model. The venture business is governed by a strong power law. Tech commentator Benedict Evans analysed returns from Horsley Bridge (a Limited Partner or someone who provides capital to venture funds), and found that across the 7,000 investments made by the venture funds Horsley Bridge backed through 1985-2014, more than half lost money, and about 6% of these investments resulted in over 60% of total returns. Below is a chart from Benedict Evans’ article covering how failure is integral to the venture model.

Back to my picks. Now when you add up the 2-3 that I do every year, and, presuming my investing career runs two decades, I would have had 50-60 picks in all, with about 20-25 picks simultaneously in operation at various stages. We now know from the above illustration of the venture law that not all of these picks have to succeed for me to do well. Being able to invest in 20-25 companies simultaneously while needing only a minority of them to do well, is a luxury that I as a VC can afford, but my founders can’t. For a founder can only pick one company at a time.

If the startup does well (becomes a unicorn, and / or at least 5x returns for all investors when acquired or listed), it is anywhere from 5 to 10+ years of the founders’ life committed to the startup. If it doesn’t do well, it may be anywhere from 2 to 5 years gone. The failed founder can still raise capital, but if s/he fails the second time, then fundraising for the third round will be tougher, and may take time. Often between failures the founder may need to work for 2-3 years to save up money, or work at the company that may have acquired their startup as part of the contract. Effectively there are perhaps 3, maybe 4, picks that the average founder has in their life, and even fewer if they first startup in their 40s.

The implication of this should be clear to founders. Take your time on the pick. Committing time to the picking process is critical. Ideally, founders shouldn’t set artificial deadlines, such as 1 or 3 months to move fast, because that will likely result in a wrong pick. One reason why artificial deadlines result in a wrong pick, is that the need to arrive at a decision fast forces founders into the path of ‘set reduction’, or reducing options. In his 20VC podcast episode, Josh Kopelman of First Round Capital says: “You say, I’m gonna quickly build a set of ideas and then spend the next three months reducing that set to find the one idea. And in most cases, the best pickers are people who are consistently focused on set expansion. They don’t feel the time pressure of an arbitrary deadline.”

The second reason why founders shouldn’t set arbitrary deadlines is so that they get the time to explore all facets and nuances of the problem, thereby giving them a better perspective on the product to build. Lloyd Tabb, co-founder of data co Looker (acquired by Google in 2019 for $2.6b), describes why founders should take their time on the problem. He says “the strength of the initial thesis was a by-product of the fact that he had been simmering the idea for his startup for quite some time”. This allowed him, as he puts it, to develop a “crisp thesis on what the problem was – and then we went directly at it.” For founders wondering what is a reasonably acceptable timeline for arriving at a pick, I think it is acceptable to take even up to a year to arrive and validate the pick (more on validation in the next section). If a year sounds like a long time, remember it is cheaper to spend 3-6 months extra across 1 to 3 cofounders honing on the pick, than spend six months across 7 to 10 members of a wider team pivoting from a bad pick.

2A.4/ Pick a specific ‘problem’, not a ‘solution’

At this point, we need to get specific about a few terms. The terms ‘startup idea’, ‘problem’ / ‘problem space’, and ‘market’ have been interchangeably used thus far in this section, in the context of what to pick. But there are important differences between these three terms. Here is how I look at these three:

- First, the term ‘startup idea’, which is a commonly used term in everyday parlance. When used, it typically refers to a specific solution or approach to solving a problem.

- The term, ‘market’, which we defined in a previous chapter, broadly refers to a set of clearly defined, or definable, buyers with similar needs and similar purchase behaviour. This is, effectively, the opportunity set.

- A problem is a dissatisfaction with a ‘job to be done’ or a goal that the customer wishes to achieve in their life. It could be a big life-changing goal (bring a pet home) or a small one (buy a healthy meal).

While the terms ‘startup idea’ and ‘market’ have their relevance, the term that I want to focus on in this chapter is ‘problem’ (or ‘problem space’ which I will use interchangeably). It is far better, I propose, to pick a problem first, and understand all aspects of the problem, before we come up with a solution, or worry about the market / buyers. Jumping into solution mode at the outset, or defining buyers early, can mean opening a one-way door rather early in the startup’s journey. Michael Seibel, the cofounder of Twitch, and a Group Partner at Y Combinator (YC) puts it well: “There is a common misconception that your idea has to be great in order to start a company. I want to destroy that misconception… Instead, my first piece of advice is to start with a problem. Starting with an idea is tricky because people immediately want to grade your idea. It’s a lot easier to start with a problem and then think about how you grade a problem.” YC encounters these solution-first pitches so frequently that they even have an internal term called SISP (Solution in Search of a Problem) to describe these.

Suril Kantaria, and Kevin Cox, cofounders of insurtech startup Savvy (YC funded, now acquired), decided to create and launch healthcare debit cards as a way to solve friction in reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses. Suril writes: “Without speaking to a single user, we developed a vision for an alternative future in health-care payments. Even without a clear grasp of what problem we were solving and for whom, we began selling.” In their conversations with potential customers, they found that “Not one person brought up health debit cards as a problem they needed to solve”. Another example of putting a product before the problem was WorkOS founder Michael Grinich’s previous startup Nylas, an email service. Obsessed with the product, Grinich filled sketchbooks with his ideas, even hiring a musician once to come up with the perfect notification sound! The result? In his words: “I was obsessed with my solution to this problem. And it meant that when the solution wasn’t exactly a bullseye, it was very hard for me to pivot away or change something.”

This lock-in or early commitment to a specific approach or solution is precisely what you need to be careful about. Even a barebones MVP (Minimum Viable Product) costs time, money, and energy. Getting customer feedback on the MVP means additional time commitment. In B2B, customers may demand some customisation before they test out the product to give you feedback, sucking up time and bandwidth from the tech team. Thus, committing to a solution or approach, and building a product, even an MVP at that, is something you want to leave till you have some certainty or at least a strongly validated belief that the specific solution is the right one (based on the information available to you). To do that, you need an in-depth understanding of the problem, and clarity on the exact problem you want to solve. This is what is termed ‘Problem Discovery’ in startup parlance. Problem discovery is at the heart of the pick, and what you are picking at this stage is effectively the problem you want to go after. The better your pick, and problem selection, the better your likely solution is, and the more likelihood of PMF. So, what makes a great pick? This is what we cover in the next section.

2A/ TLDR

Getting ‘the pick’, or the problem, to go after, is the single biggest decision the founder / founders will take early on in their startup journeys. Its importance comes from the fact that

- once the pick is determined, the ‘constraints and boundaries’ of what you are going to be working on for the rest of the 2-10+ years is set. Further, where you play has a far bigger influence on your success than how you play (the median pharma company makes higher margins than the best airline).

- it is difficult to change the problem you are working on; the specific solution may be more amenable to shift / pivot, but not the problem. Conversely it is far easier or cheaper to change the problem when you are two-three co-founders than change the solution when you are a team of 8-10 people.

- each pick consumes 2-10+ years of a founder’s life, and there are at best 3-4 picks the founder can work on. Hence, take your time to get the pick right. The best founders don’t hesitate to spend a lot of time arriving at their pick.

Above all, focus on the problem, and do not commit to a specific solution early.

2B/ What makes a great pick?

2B.1/ What makes a great pick, or problem?

There are three elements or criteria that determine how great a pick is. Your pick doesn’t necessarily need to meet all three criteria, but it helps. The three elements are:

1) a large ‘attackable’ problem,

2) an inflection point / right timing,

3) founder-problem fit.

How did I arrive at these three elements? Well, they are derived from the questions that VCs ask to determine if a startup has potential for success, and is thus funding-worthy. To determine a startup’s potential for Product Market Fit (PMF) and eventual success, VCs primarily look for answers to ‘why this?’, ‘why now’, and ‘why you?’. If you are wondering how VCs determined that these were relevant questions to ask, then the answer is that these likely emerged over long years of trial and error by seeing which investments succeed and why, and thereby arriving at the underlying criteria of market, product, team, that explain startup success best. The questions of ‘why this?’, ‘why now’, and ‘why you?’ correspond to these three criteria.

The first, ‘why this?’ asks if there are large realisable revenue / profit pools to go after; or as I like to ask: ‘is this a large attackable market?’ For those of you are Richard Hamming fans, you know where I stole the word ‘attackable’ from! How large is large? Well, as of 2025, for the Indian market, VCs want to know if you can get to $100m in revenue, and EBITDA profitability in 7-8 years. This means a rough valuation of $1b or unicorn status, and is likely worked backwards from this. For the U.S., large might mean $250m or even more. The second, ‘why now’ asks whether there are any specific tailwinds thrusting this problem space ahead, or a timing that makes it particularly unmissable. The third, ‘why you?’ asks why the founders are the best folks to solve the problem, essentially seeking if there is founder-problem fit.

Let us now go through these three elements one by one.

2B.2/ Large ‘attackable’ problem

As a founder, you want a problem that customers care about, and you also want to know that there are a large number of such potential customers, and thus indicates a large market or large TAM (Total Addressable Market). Customer conversations can provide some evidence that the problem is real. But, how do you determine that there are many such customers? One way is to look at the broader problem space and see if there are any large companies operating in the space making sizable revenue (as a proxy for demand / number of customers). For instance, take English language learning in India. It seems a meaningful problem – lack of English fluency locks you out of the formal economy in India, and reduces your earning power. But when you look at the number of startups or even companies in India that make meaningful revenue in the problem space you don’t find any. Does that mean you should never launch one? Well, no! But yes, your pick is perhaps less compelling than a pick with a comparable problem that has several large companies making meaningful revenue.

There are of course several other ways to validate that you are in a large market. One is to look at Google search trends and see if there is sufficient volume or not. Google search is a powerful signal of intent, and if it is growing or large relative to other categories it is a good sign. If this is low volume, and / or not growing that means it is not yet a large market, and entering it runs the risk of having to do category creation, and invest heavily into customer awareness creation. A similar signal comes from keyword bidding data and prices. Then there is VC funding data, job posts of existing players even if nascent and seeing if they are growing, etc. You can also look at combinations of these to arrive at a consolidated signal of a large market.

Let us take a real life example of a pick failing the large market test. This is the story of Srikrishnan ‘Sri’ Ganesan and Hotline. Sri is now co-founder and CEO of onboarding SaaS startup Rocketlane ($24m Series B led by 8VC in Jun’24). Then, Sri was part of Freshworks, running Hotline, a customer support experience / chat app within mobile apps (Hotline was a rebranded souped-up version of his startup Konotor, which was acquired by Freshworks). When he found Hotline struggling to take off, despite attempts at cross-selling Freshworks’ existing suite of products, he decided to dig deeper. He says: “I took a break from work and went and met all kinds of folks in the space to just understand why am I not seeing traction first? And one of the things I heard is, and this is from a senior marketing leader in the US who said, if you look at retail as a category for example for Macy’s, mobile is the 13th biggest store for them that means there are 11 physical stores and an online web which is doing more than mobile app.” Effectively Hotline was not solving an important-enough problem for retailers.

Through this and other conversations Sri came to the painful realisation that they were playing in a small market. In Sri’s words: “ … we realised that our competitors at that time…none of them were growing fast. On the other hand, something like Intercom in the web messaging space grew from 1 to 50 million in two years or something. So there was all that traction happening in some other market and we were playing somewhere else and focused only on mobile.” Clearly they weren’t playing in the right market. Freshworks took the cue, reworked Hotline, and launched it as Freshchat, an app that worked for websites too, and very soon it was Freshworks’ fastest-selling product. Today, when younger founders struggling with traction, reach out to Sri for his advice he asks them: “If you are not growing, I either challenge them with if there’s someone else in your space that’s growing fast, why not you, or if no one in your space is growing fast, are you sure it’s the right space?”

There are of course some legitimate exceptions to the above heuristic that if there is no large or growing player in the problem space you have chosen, it is a bad pick. Tobi Lutke, the founder of Shopify remarked in a podcast about how a VC passed on him because the addressable market was very small, about “40-50k online stores then”. Years later after Shopify had struck it big, the VC reached out and asked Tobi what he had missed, and Tobi replied “You were actually correct, but what you didn’t realize was that Shopify was the solution to the very problem you identified. The reason there were only 40,000 online stores was because it was hard, expensive, and …complex… which Shopify, … smoothed over and made simple to do.” Like Shopify which created and expanded the online enablement for SMB market, there is Uber which created the rideshare market. The market size of rideshare apps before Uber emerged was zero. It was Uber’s ease of ordering a cab that unlocked the rideshare market. Similarly for Airbnb and homestays, Calm and mindfulness. Jason Calacanis puts it well: “The best products induce a market to manifest itself.”

How do founders solving problems for a narrow or nascent market overcome the challenge of explaining TAM to VCs? Well, they can use the concepts of Total Expandable Market, or Total Persuadable Market, or Total Future Market to persuade investors. These are all constructs for, yes ‘the TAM is small right now, but with initial success and later expansion across users, use cases, and going multiproduct, we will expand the TAM’.

Thus far, we have been discussing the ‘large’ part of the ‘large attackable problem’ element. Now to the ‘attackable’ part. What does ‘attackable’ mean in this context? I stole this term from a famous speech ‘You and Your Research’ by Richard Hamming, the legendary computer scientist, where he talks about how scientists should pick a research problem that is both consequential and has an attack or approach angle. What Richard Hamming says of scientific research, holds true for startup problems too. If you have an attack, then it means that a working solution to address the problem can be built without investing a lot of resources (people, money, time).

Getting back to the English learning example, no app or software-led solution so far has been able to get a large number of blue-collar Indians to speak English fluently. There are very likely many factors at play here, including learner motivation, but essentially it seems that the only truly effective solution looks like a K12 school or growing up in an environment where everybody around you speaks English. This is not a low-effort solution. Thus the English learning problem in India is potentially large but not attackable. This is a case where the attackability is hindered by the inability of the product to address the problem.

Alternatively, there are cases where the attackability is hindered by the nature of the market and the competitive dynamics of the market. For instance, there may be existing players in intense competition, and therefore limited attack angles available for a new entrant. And, if the existing players are already doing a good job of addressing the problem, then there is limited scope to take them on. Indian UPI payment apps are a good example. PhonePe and Google Pay have 80%+ share between them, and are an effective duopoly. That said there is one way in which startups can overcome the constraints of a limited budget to take on well-funded well-run incumbents. That is by changing the frame of reference / comparison, accompanied by a compelling narrative. Namma Yatri and Rapido have been able to penetrate the Indian ride share market (which was effectively a duopoly between Uber and Ola by not charging the drivers per transaction, but a fixed daily fee (₹25 per day for an auto). This enabled them to get drivers on the Uber / Ola platform to switch, in turn making it easier for users to access rides, and creating a positive loop.

Mike Maples, Jr., cofounder of Floodgate Ventures, and coauthor of the recent book Pattern Breakers describes this well: “you want to force a choice and not a comparison… If everybody’s selling apples, I can’t be a 10 times better apple. I want to be the world’s first banana.” He continues, “And most people might not like bananas, but all the people in the world who do are going to say, Oh my gosh, where have you been all my life? And most of the startups that have great success, they kind of have that energy at first.“ The example he cites is of Tesla cars, which was sold on the narrative of lower carbon footprint and sustainability versus its ICE peers. Founders going against well-ensconced competitors could choose to use this strategy, of not going head on with the existing players, but instead changing the frame of reference, and fashioning a compelling narrative / showcasing a desirable future, and positioning your approach as the one that will take believers in that future to their promised land, to enhance attackability of their pick. With this, we now wrap the ‘attackable’ part of ‘large attackable problem’.

2B.3/ Inflection points, ‘why now?’, and insights

Now, it is good to be in a large market with good attack angles. But it is even better when there are strong tailwinds behind the market, thanks to an inflection point. A good definition of inflection points or inflections is “external events with the potential to significantly alter how people think, feel, act” – this via Pattern Breakers by Mike Maples, Jr.,. Inflections matter because they create a tailwind that provides significant momentum to the startup attacking the problem. An example Maples Jr., cites in the book is of the GPS locator chip in the iPhone 3G which made Uber, Lyft, and all ridesharing apps possible, and / or accelerated their growth. Other examples include Instagram which took advantage of the iphone camera and the app store, Coinbase which benefited from the emergence of bitcoin and the crypto movement, and shortform video apps in India benefitting from UPI autopay (and also from Jio’s cheap bandwidth), etc. It is not always technological inflections. Sometimes it is a regulatory shift such as easing of regulations around remote healthcare, (thanks to COVID-19) leading to a spurt in telemedicine apps. Sometimes it is a combined regulatory + cultural inflection that made remote working / digital nomadism popular, leading to payroll processor for global employees, Deel.

VCs like startups that benefit from an inflection point because they answer the ‘why now’ question. Inflections provide growth momentum; it is akin to a stone rolling downhill. Additionally, every technological shift opens up the room to new actors, both winners and losers, and VCs ideally want to take advantage of these technological shifts / inflections (sometimes regulatory shifts or inflections) to back the new wave of winners who will emerge. Not focusing on inflection-led firms means they will miss out on a whole class of potential winners. Hence the aggressive cash infusions into hot sectors as we see with AI today. While this creates an opening for founders to get started, it can also get tricky. You may think you are riding an inflection point only to realise that you are early. Webvan, Google Glass, Apple Newton are all examples of products well before their time. Their successors, Instacart, Ray-Ban Meta glasses, and the PalmPilot benefited from advances in technology and cultural attitudes / practices that made adoption easier. Also, remember, inflections are not always permanent. In the early days of the pandemic, virtual conferencing startups were red hot and grew rapidly, e.g., Hopin, Hubilo etc., but once the pandemic waned their fortunes did too.

As we see above, it is not easy to get ‘why now’ exactly right. The conditions that provided tailwinds to your startup can shift as we see with Hopin, and sometimes you may be riding the forefront of a technological trend like Webvan, but the market may still be small. Still, founders would do well to ask themselves ‘why now?’ when they are honing on a pick. Dylan Field, the cofounder of Figma, describes it well: “When you’re starting a company, it’s really useful to ask the question: why now? It’s a really useful framework. It can be societal; maybe there’s some new cultural trend. Perhaps it’s regulatory; some law has been passed or repealed. I like the technological version. For us, we saw drones in 2012 and WebGL as a few technologies that were happening. Because of them, new possibilities were suddenly there. On the drone side, we didn’t get very far … and then we focused on WebGL instead … then eventually sort of shifted our attention to design. I had been a design intern at Flipboard, and that kind of helped me realize what would be possible there.”

Allied to inflections, and tailwinds, is insight. Figma succeeded because the inflection point of WebGL’s emergence was married to the insight of it being used for multiplayer UI (for the first time, a design document could be edited like a google doc). Similarly, the GPS locator chip in the iPhone, was an inflection point married to Uber’s insight of using it to track a vehicle. MyGate, a visitor management app for India’s gated societies, was born out of an insight that security guards were snowed under the sudden growth of ecommerce deliveries (an inflection point) and now needed an automated tool to manage access and gatekeeping. Mike Maples, Jr., elaborates: “An insight is a non-obvious truth about how one or more inflections can be harnessed to change people’s behavior.” While inflection points are about a tech wave, or regulatory / cultural shift, insight is fundamentally about customer behaviour. Inflections provide the ‘why now?’ and the insight helps you take advantage of it.

2B.4/ Founder-problem fit, or ‘why you?’

Founder-problem fit covers whether the founder or team that is out to solve the problem have any unfair advantages or a better right to solve this problem than other teams. This right to win manifests via the founders’ deep understanding of the problem or the domain in which the startup is playing. It also helps if the problem has emerged from the lived experience of the founder. Linear emerged from the founders’ personal pain from using Jira, a popular but widely disliked issue tracking + project management software, at their previous startups. Alyssa Ravasio founded Hipcamp after struggling to book an outdoor camping site, and finding the experience broken. Startups that emerge from the personal pain of the founders are likely to be persisted with, despite significant setbacks, given that founders are personally motivated to solve the problem. Secondly, when a founder is solving a personal pain, they have a better understanding of the customer for, they are the customer! Given this, most VCs believe that startups born out of personal pain signal stronger founder-problem fit.

Sometimes, it may not be personal pain as much as from a deep understanding of the domain. Mayank Kumar founded edtech co Upgrad after having garnered significant experience in the domain having worked at consulting co Parthenon and investor Bertelsmann, both of whom had a strong focus on education. Bumble was born when Whitney Wolfe Herd was approached to start up again in the dating sphere, after her past challenges at Tinder. Assaf Rappaport and his cofounders founded cybersecurity rocketship Wiz (acquired by Google for $32b), after long years of experience in the cybersecurity space. What all of these examples have in common is that the founders have a deep understanding of the domain or problem, and can get to grips with nuances, peer around corners, and thereby improve the chances of success. Thus, deep domain experience is a signal of depth of understanding of a problem, and is another signifier of strong founder-problem fit.

Chris Dixon, General Partner at A16Z concurs: “…it takes time to reach product/market fit. Founders have to choose a market long before they know if they will reach product/market fit. In my opinion, the best predictor of whether a startup will achieve product/market fit is … whether there is ‘founder/market fit’. Founder/market fit means the founders have a deep understanding of the market they are entering, and are people who personify their product, business and ultimately their company.” In general the earlier the stage at which the VC invests, the more likely that ‘why you?’ / founder market fit / founder problem fit becomes critical. Because at that early stage there is very little data or information outside of the problem / market / idea and the team. So what the VC tries to do is to estimate the strength of the fit between the two.

That said, there are many examples of successful companies with founders who had limited experience in the domain they were starting up in. The cofounders of DoorDash including Tony Xu had no relevant experience in the restaurant industry or logistics. Nat Turner and Zach Weinberg founded Flatiron Health (acquired by Roche for $1.9b in 2018) without any prior healthcare experience. Per Turner: “while a bit of experience — roughly under a couple of years — can be helpful, most of the time it’s actually a detriment … because you’re so used to the constraints of the industry, how the whole system works and the incentives, that you can’t see through the mess.” In fact, it is more common to have limited domain experience than more. Per Super Founders by Ali Tamaseb, who studied unicorns created between 2005 and 2018, shared that in consumer startups only 30% had directly relevant work experience, while for enterprise tech, the number was only 40%. The exception is healthcare, life sciences and biotech, where 75% of founders had directly relevant experience.

After having read through examples of founders with no prior domain experience succeeding, and failing, my takeaway is that prior domain experience helps, but it is not mandatory. Its absence can be overcome with domain immersion. For instance, the founders of Flatiron Health, Nat Turner and Zach Weinberg, travelled to 50+ community oncology centres in small town USA, “shadowing doctors and finding out what it’s really like to be both a patient and a physician in cancer care” and finally arriving the challenges of leveraging patient data to enhance outcomes as the problem to pursue in oncology. Impressively, Rajat Suri worked as a waiter to research the restaurant business prior to launching his ordering automation app Presto. To repeat, many VCs will lazily use prior domain experience as a shorthand to judge you on founder-problem fit, or ‘why you?’ and thus the onus is on you to signal your domain expertise, and your right to win.

2B/ TLDR

In the last section, we learnt that getting the right pick (or problem that the startup is addressing) is a key criteria for success, and that founders should not rush ‘the pick’ phase of startup building. In this section we learnt that to get the pick right we need to evaluate the pick by how they rank on the three key elements or criteria of the pick: large attackable problem, inflection points / why now, and founder-problem fit. They are in turn derived from the three questions VCs ask to judge the potential success of the startup: 1) Why this? 2) Why now? 3) Why you? While it is not mandatory for a pick to be ranked highly on all the three criteria (large attackable market, inflection point / why now, founder-problem fit), it helps. After all, getting the pick right has a huge impact on the eventual success of the startup, and your next 2-10+ years, so why not strive for all three?

2B/ Additional readings

Making sure the problem fits the large and attackable criteria is my preferred approach, but this isn’t the only exclusive approach. A couple others:

- Venture investor Hunter Walk of Homebrew likes to use the Large Urgent Valuable (LUV) framework to determine if the problem is worth backing. Essentially, is the problem large, is it urgent, and is it valuable? Ideally he wants to see a yes to all three. This is short and subjective.

- Jason Cohen, cofounder WPEngine and Smart Bear, has a detailed and quantitative framework to estimate problem attractiveness. He looks for the following criteria – plausibility (number of potential customers who have the problem), self-awareness (whether they are willing to solve the problem), lucrativeness (whether there is a budget), liquidity or frequency of decision, eagerness or attitude towards your company, and finally, if the customer relationship will endure. His proprietary framework has a scoring chart, which can be used to arrive at a score that serves as a guide to the viability of the problem and the opportunity size.

*

Founding Hypothesis: Jake Knapp who came up with the Design Sprint methodology, teams up with Jake Zeratsky to write how founders can lay out your pick or approach into a framework they call a founding hypothesis, which asks them to list out the problem they are going after, the likely customer, the approach, and finally their differentiation (see image below). It is a handy way to structure the pick, and forces clarity early on. The article also has a few more bells and whistles, including the process of running a ‘Foundation Sprint’ to structure the pick better and arrive at a common language and buy-in for all founders. Certainly worth a read (paywalled).

2C/ How to pick

2C.1/ There are four routes for a founder to pick a problem

There are broadly four routes to arriving at a problem to work on. These are personal pain, personal experience, prospecting, and finally opportunism. Let us look at these one by one.

The first route is through personal pain, i.e., when the problem or problem space that you wish to work in is because of something you have personally deeply felt troubled or bothered by, and for which you wished to see a solution. Some examples:

- Garrett Camp came up with Uber, after paying $800 for hiring a car to take him and his friends around on New Year’s Eve 2007.

- Edith Harbaugh founded feature and release management software LaunchDarkly, to solve the frustrations she had around migration and rollouts to different users during her stints at TripIt, Concur, and Vignette. She saw every company she worked at struggle to stage releases of software to its users, and felt there should be software that helps companies do it better.

- Deepinder Goyal launched FoodieBay (now Zomato), after he saw how folks in Bain’s Gurgaon office had to await their turn to see a set of menus and order (circa 2008); he scanned and put it on an intranet. Then he added more menus, and then expanded it outside Bain as Foodiebay.

The second route is through what I call personal experience, i.e., where the idea evolves from, or is triggered by what you have experienced in the course of your work or personal life. For instance you have worked in an insurance company, and in the course of that you see that there is an opportunity to improve some process (say cashless claims) and decide to start up there. Some examples:

- Brian Armstrong was at Airbnb and he saw the challenges of money transfer to hosts across the 190 countries they were operating in. When he saw the Bitcoin whitepaper on Hacker News, he saw that crypto could help in enabling greater financial participation in the global economy, leading him to start Coinbase.

- Mathilde Collin and Laurent Perrin started Front, after their past experiences. Mathilde saw the importance of email as the premier work tool, and wanted to make it better, and Laurent, wanted to create a lightweight customer support tool. Their ideas converged into a shared inbox tool for customer support and service use cases in Front.

- Girish Mathrubootham had been building on-premise helpdesk systems since 2004 at Zoho. He came across an article in Hacker News about Zendesk increasing its prices, and read a comment that there could be an opportunity to create an affordably priced helpdesk competitor. That inspired him to launch Freshdesk (now Freshworks)

The key difference between Personal Pain vs Personal Experience is that in the former the founder is the customer, while in the latter the founder knows customers well from his past experience.

The third route is arriving at the problem to work on through a long (or occasionally short) process of prospecting – evaluating different industries, talking to different people (other founders, VCs, experts), looking at hot sectors, brainstorming and whiteboarding with cofounders, etc., to arrive at a problem space that looks meaningful from a market size perspective, and one that personally excites the cofounders.

- Christina Cacioppo of Vanta, arrived at SOC2 compliance as a productized service, through a long process of brainstorming, ideating, and rejecting (one of the rejected ideas was a voice assistant for lab workers).

- Marco Zappacosta and his co-founders ”brainstormed on weekly phone calls”, and bounced potential ideas off each other, to arrive at Thumbtack, a marketplace enabling anyone to access home improvement and professional services.

- Deep Kalra, experienced the power of the internet (this was late ‘99 or early 2000) after getting a higher price online while selling his wife’s car, and explored ideas around online broking and online travel and chose the latter. This became MakeMyTrip.

The fourth route is via opportunism, where you see a potential opportunity to replicate what exists in another market / geography, e.g., doing a X of India. This is likely how Flipkart, Ola, Dealshare etc., started. The founders of Flipkart were working in Amazon’s offshore development centre in Bangalore, and decided to create an ecommerce platform for India. In the case of Ola, there is the much quoted story of cofounder Bhavish Aggarwal, having a poor taxi experience while travelling from Bangalore to Bandipur, which gave him the idea for a taxi cab company. It could be personal pain but I feel it was likely semi-opportunistic as Uber, Lyft (then Zymride) were funded and operational by then. The founders of Dealshare were inspired to create the PDD of India.

Another way to arrive at your present idea or problem space is through a pivot; that is, by starting with one of the above four approaches, and when hit with a roadblock or chances of imminent failure, explore an alternative idea based on what you have learnt in the course of the journey thus far. Some examples:

- You can take the most popular feature, which may have been a sidebar feature and not the main offering, and turn it into a product, e.g., Stewart Butterfield shut down Glitch, a game they were working on, and converted the internal tool they had built to “organise file exchanges among their development team” into Slack.

- Sometimes, it is understanding that the product you have built for a certain market could be relevant for other markets, e.g., Sarah Leary and her team initially built Fanbase, an online community for sports enthusiasts. When Fanbase struggled to grow, they leveraged the community elements of the product, to pivot into a hyperlocal community and social networking app which they named Nextdoor.

- Finally, it is seeing that the biggest users of your product are using it to meet their unmet needs, and pivoting your product to meet their needs, e.g., Meesho pivoted twice, first moving from serving neighbour stores to serve individual resellers, and then again pivoting away from resellers to service individual buyers.

Do VCs prefer a specific route? Well, I haven’t seen it explicitly stated anywhere though I feel VCs do have a slight affinity for picks emerging from personal pain (more on this in the next section). Personally I prefer Pivot > Personal Pain > Personal Experience > Prospecting > Opportunistic. The reason Pivot comes on top is that the founders have been through one round of iteration and market feedback, and hopefully have been pulled in the right direction based on market feedback. The risk is now reduced to some extent. Next is personal pain because if it is something that deeply matters to you, and you are scratching your itch, then it is likely that you are going to stick with it for longer, even in hard times. Opportunism comes lowest for the same reason that personal pain comes highest. It is a tactical approach to solving for fundraising or deciding, basis what is hot. Here I am not sure the founder will stick with the problem if s/he encounters hard times. That said, when I evaluate a startup, this preference or bias alone is not enough to decide one way or the other, but instead it gets weighted as one of the rubrics in the final decision.

2C.2/ The pick has two phases: ‘Problem Discovery’ and ‘Problem Validation’

Problem discovery, and problem validation, constitute the two phases of arriving at, and firming on the pick. Problem discovery is where the founder devotes time to figuring out the right problem s/he wants to work on. Following problem discovery is problem validation, where the founder has to validate or confirm that the problem space they have chosen is large and meaningful enough for them to devote the next few years to work on it, primarily by getting some signals of a large enough market or customer set who care about the problem and the potential solution.

When we combine the two phases of the pick – problem discovery and problem validation – with the routes by which we can arrive at a pick – via pain, personal experience, prospecting, or opportunism – we get the following matrix of ‘phases x routes’.

Let us dwell a bit more deeply into these two phases of the pick: problem discovery, and problem validation, in the next two sections of this chapter. First, we take up problem discovery.

2C.3/ Problem discovery

What does doing problem discovery actually look like? It is a combination of primary research, i.e., conversations with potential users, experts, founders or operators working in the area, and secondary or desktop research, i.e., reading on the interwebs, reviewing scientific literature etc., as to figure out a potentially large problem you want to work on. Problem discovery is relevant largely to the pick via prospecting route (as, in the others, you arrive at the pick via an aha moment basis your pain, or experience). That said, even in the pick via pain route, you may need to narrow down the problem to a sharper sub-problem. This is where the principles of problem discovery come in handy. Let me illustrate this through a hypothetical example.

Let us assume that the challenges of dealing with an elderly family member, and the personal pain, lead you to eldercare as the space you want to work on. It also seems like a large growing market, and each cohort of elders seem to have more disposable income than the previous cohort, so it seems like a growing, economically vibrant market. By reading a lot of articles, scientific papers, books etc., as well as by talking to people running senior living accommodation, potential customers who could be either older people or their progeny, experts in the space, or brainstorming with your cofounders etc., you arrive at a problem: the biggest danger to healthspan, and thus lifespan, of older folks is falls, and the second biggest problem is loneliness (I am guessing!). You now have the main problem you want to go after – falls and what can be done to reduce it – and a backup problem, that of combating loneliness in older folks. Thus as we saw here, even for pick via pain route, the process of problem discovery comes in handy to help narrow down the problem, to a specific sharper sub-problem.

In the above hypothetical example, the founder had clarity on who to speak to / reach out to, given that personal pain had led them to the broader problem space of eldercare. It made sense to reach out to experts / potential users / founders in this category. But in cases where the founder is picking via prospecting, they will need to cast the net wider. The focus here, as we read in the previous section, should be on ‘set expansion’, as Josh Kopelman, of First Round Capital puts it. Set expansion is essentially widening your choice set, by getting more and more options around what problem spaces to pick. Given the centrality of the pick in the success of your venture, it makes sense to make sure you aren’t missing out on a problem space that may have been more relevant. The best way to do that is to:

- budget a reasonable amount of time for problem discovery. Six to nine months is ideal, but don’t worry if it is longer, for every month invested in the pick stage will save you a few more (expensive) months of pivots down the line, and

- do lots of conversations.

How many is lots? Well, Sasha Orloff who exited as cofounder and CEO of LendUp, did “100 coffee chats with founders, CEOs and investors to gather advice for his next move“. This became AI-powered accounting startup Puzzle Financial. The community app Kutumb’s ($26m Series A led by Tiger Global in June ‘21) founders ran ads on Facebook inviting people to send in ideas for apps that didn’t exist but which they wished to see built. A large number responded, and the four cofounders spoke to over 2,000 respondents to determine what to build. That is a lot though! I haven’t come across any definitive guideline on how many conversations you need to have at the problem discovery stage specifically – most of the data online on the topic of conversation count is for customer discovery or validation calls.

In fact I don’t think there is a magic number of conversations or calls needed at this stage. Instead I recommend that you could keep doing conversations – for anywhere 2-3 to 6-9 months, ideally don’t exceed a year – till you arrive at three to four problems that per your and / or a friendly VC’s estimates, meets at least two of the three criteria of a good pick (founder problem fit, why now, large attackable problem). At this stage we can say that the phase of problem discovery is over, and it is time to move to the phase of problem validation, where you can take these problems one by one and cycle through the problem validation phase for each.

Three points to note on problem discovery:

1/ While it is ideal to have three or four problems to take to the Problem Validation phase, if you are picking via pain or personal experience, it is likely that you may have fewer problems or prospective picks, perhaps even one. That is fine too, though I encourage you to try and narrow a broad problem to two sub-problems if possible. If we go by the above example of eldercare, the subproblems were falls and loneliness.

2/ I mentioned that the problems you have identified at the end of the discovery phase should meet two of the three criteria that make a great pick. One of these criteria is a Large, Attackable Problem. In this regard, how important is it for the problem to be ‘large’? What TAM is sufficient? Well, if you are validating a problem that came through prospecting (or opportunism) then you should want a large TAM. But if you are validating a pick or a problem that came via pain or personal experience, then you can live with a medium-sized initial TAM provided you have glimpses into a user persona that needs to solve this problem desperately.

The reason is that there are enough examples of startups starting with a narrow wedge of desperate users, whose problems the founder(s) deeply cares about, satisfying them through a great product / solution, and then leveraging that user love to gradually expand to more and more users. I believe that if the founder deeply cares about a problem (pick via pain or even personal experience) then they shouldn’t worry as much about the size of the TAM initially as much as the size of the pain.

3/ I have two pieces of advice on conducting customer conversations effectively in this phase.

- Todd Jackson of First Round Capital, suggests understanding the root cause behind a customer problem through a process of repeatedly asking questions till you hit the fundamental underlying cause (kind of like the Toyota 5 Whys approach). “You need to really dig for the deep needs — users can’t verbalise them directly”, he says.

- Mahima Chawla of leave management software Cocoon, advises: “Go in with a very open mind. Don’t try to make something a problem, because if you do you’re going to find the evidence to support it. Really just truly listen to what the person you’re interviewing is actually saying and notice if there is a trend.” She concludes by saying “If it feels like you’re pulling teeth to find the pain point, you haven’t found a problem worth solving.”

2C.4/ Problem validation

As with problem discovery, the phase of problem validation too is conducted via a combination of secondary / desktop research, and customer / user conversations. But the emphasis here is different, given that the problem discovery phase was about divergence or set expansion, but the problem validation phase is about convergence or set reduction. The problem discovery phase is about arriving at the problem(s) to work on. In Problem Validation, you are seeking to figure out if the problem(s) you have selected is a meaningful enough space to work on for a long while to come. Thus, the questions you direct at potential users, that is people who you think have this problem or you think are likely to have this problem, are aimed at getting their perspective on the specific problem you have in mind. You are validating that potential users or customers care about the problem deeply.

As much as what customers say, it is what they do that matters. Radhika Agarwal, a founder in the early stages of building a beauty startup told me: “What they say stems from a human need to please people, or cater to their own image of themselves, or their idea of who they want to be rather than who they really are. What they do is the only signal that counts.” I couldn’t agree more. Hence, in customer conversations, look for proxies of the problem’s importance for the customer, such as the customer using a bandaid or workaround, or even building an internal tool themselves to address the problem that you want to work on.

A good example of customers building it themselves as a proxy for problem importance comes from Merge, a platform that makes it easy to add integrations with popular software services into your product. The founders of Merge, Shensi Ding and Gil Fletcher, had both faced challenges with integrations in their respective companies. They set out to validate the problem by speaking to about 100 companies across six months – they learned that the problem was real, and that companies were “paying a lot of money for vendors and were deeply unhappy with the quality”. They were throwing people at the problem and trying to build it themselves. This was a strong proxy for problem importance at the customer end. [

Look out for similar strong signals in conversations too. What you are seeking is a ‘hell yes’, and not just a lukewarm yes. Remember most people don’t know you well and hence won’t be very direct. They will not say no, but will instead couch it in “That seems interesting” or “Keep me posted” etc. This is as good as a no! As a startup you need desperate customers to buy your solution. This is because buying from a fledgling setup is a risk for a buyer, so they need to overcome reservations about whether the company will last, whether it will be secure, and so on. Only a desperate customer will overcome these internal reservations to plump for your product. Hence look for strong signals that customers are indeed wrestling with these problems, and prioritising them highly.

A good principle to keep in mind around prioritisation is to “make sure you are addressing ‘the’ problem, and not ‘a’ problem for the customer.” Per Shreyas Doshi’s customer problems stack rank framework, every organisation has a stack rank of priorities, and if you are not addressing any of those high priority problems for the org, your chances of product adoption, and hence eventual PMF, are weak. Vanta’s cofounder Christina Cacioppo was drawn to security compliance processes as a pick, when she saw how much of a priority this was for Figma (they were on the verge of signing a big enterprise customer, with stringent security practices, and if Figma didn’t clear them they wouldn’t be able to sign the account). She saw security compliance as a hurdle in the way of revenue and saw that it would be a high priority for the company. At the end of each customer convo ask yourself: Is the problem you are addressing or seeking to address, high enough on the users priorities? Do they care enough?

What happens if they don’t care enough? What if a majority of prospective users you talk to signal that the problem is not high up on their priority list? Well, then this is where you take out the backup problem(s) and move to validate that. But if you don’t have a back up plan, then it is time for you to go one step back to problem discovery and figure out another problem. While it means you have to go figure out a new problem, and this could take another 2 to 6 months even (and then you have to revalidate it), it is still better than spending 3 – 4 years on taking the solution to market and failing. Now, take a different scenario: what if your first pick has strong customer signals; do you take that as the final pick and stop there? No! My suggestion is not to stop the problem validation process, but to continue with it for the next two-three as well. You never know if the others will be even stronger!

Thus, at the end of the problem validation phase, we are left with a pick: the problem that we want to go after, and one which early customer conversations have validated as a problem that customers genuinely care about. Now, how many conversations do we need in problem validation? In this context, Todd Jackson, Partner at First Round Capital, suggests talking to at least 50 customers for B2B as “since different businesses have very different buying patterns” per him. In B2C he says you can sometimes get away with a smaller number because different demographics may look at the problem similarly. I have reviewed startup literature and I have not come across any definitive recommended number of problem validation conversations thus far. I have seen numbers ranging from 10-15 per Ash Maurya, to 100 per Steve Blank. Lenny Rachitsky says that B2B founders spoke to “a median of 30 potential customers” before concluding that their pick was “solid”. My recommendation is to target about 10-15 convos per week, and at the end of a month or so, after about 50 convos, take stock to see if the pick is getting consistently strong signals from prospective customers or users. Rotate through the three to four picks and at the end of the quarter you will know if one of them has made it, or if you need to go back to problem discovery again.

Finally once you are done with the problem validation process, you will hopefully have a problem, which meets two of the three criteria of a good / great pick, and be seen as an important problem by the customer personas whose problems you are targeting. A natural question at this point is what format the pick is in. While sometimes some ideas cannot be expressed without a slide deck or a Figma file / artifact, it is absolutely fine if the pick exists just as a problem / idea / verbal construct too. Well, irrespective of whether it is a verbal construct or a Figma artifact, congrats! You now have a pick, and it is time to build!

In the upcoming sections, we will take the different routes to the pick, and run through the process of how founders should arrive at a successful pick. We will also cover examples of successful and some not so successful startup stories to illustrate the process. Founders who have already figured out a specific pick can go directly to that section and skip the others. For instance, if you plan to arrive at your pick through prospecting – identifying various sectors, and potential problem spaces and opportunities in those and filtering them to one – then directly go to that section.

2C/ TLDR

This section covers how to arrive at the pick, or the key problem to go after. We learnt that there are four broad routes by which founders can arrive at the pick – via personal pain, via personal experience, via prospecting or systematic exploration and via opportunism. Finally you can also arrive at a pick by pivoting from a different initial pick. To arrive at the pick, founders need to work through two phases. The first is problem discovery, where you expand the set of problems to pursue, through primary research (conversations with potential customers and experts) and secondary desktop research, and hone in on a problem or two or three to pursue. The second phase is problem validation, where you again conduct conversations with customers, and do desktop research if needed, to validate that the problems you have picked are meaningful to explore.

Problem discovery may be less important when you arrive at the pick via pain or personal experience or opportunism, given you are already clear on what to pursue. Similarly both problem discovery and problem validation may be less important for pick via pivoting, given customers have pulled you towards what they think is the right path for you to pursue. It is only in pick via prospecting that you need to systematically work through both problem discovery and problem validation.

2C/ Additional readings

The single best resource for learning how to conduct customer conversations better, especially during the problem validation phase, is the book ‘The Mom Test’ by Rob Fitzpatrick. It is a short book, and the time of 3-4 hours invested in reading it is well worth it in terms of impact. The name comes from asking questions in such a manner that even your mom can’t lie to you, because your mom will always think whatever you tell her is a great idea, and respond effusively. Hence your questions need to pass ‘the mom test’! The book encourages you to ask questions about your customers’ lives – “their problems, cares, constraints, and goals” and use these “concrete facts about our customer’s lives” to “take your own visionary leap to a solution”. The book says that the later you mention your idea to the customer you are interviewing, the better. In fact, if you don’t mention your idea, the better the questions you will ask, and the more insights you will extract from the conversation. The book puts it well: “It boils down to this: you aren’t allowed to tell them what their problem is, and in return, they aren’t allowed to tell you what to build. They own the problem, you own the solution.”

*

James Hawkins, cofounder of Posthog, has a good writeup on validating the idea by talking to potential users, including how to reach out to potential customers, typical failure modes etc. This is part of a longer piece on working towards product-market fit. In the piece, see level 2 of his 5 level framework: “Validate the problem really exists by talking to users”.

*

This piece on lessons learnt from 20 different paths to PMF in the First Round Review also has a detailed section on problem discovery and problem validation. The First Round Review also had a good piece on 12 frameworks for generating startup ideas, which I thought was a good read on the topic of problem discovery.

*

Finally, this piece, a guest post by Todd Jackson of First Round Capital in the Lenny Rachitsky newsletter on how to validate your startup idea was a good read. It is more solution validation than problem validation but still has some useful insights for the problem validation phase.

2D/ Pick via pain or personal experiences

2D.1/ On picking via pain or personal experience

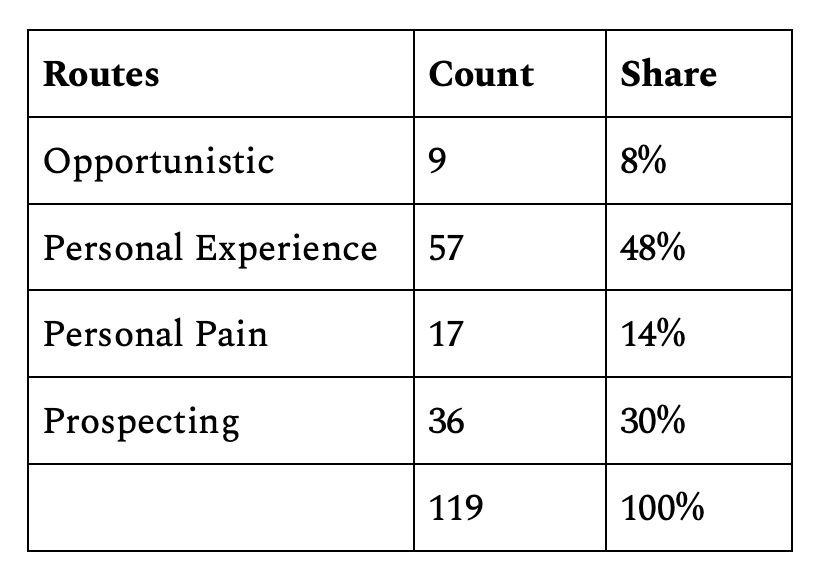

Lenny Rachitsky estimates that about 50% of successful consumer companies, and 40% of successful B2B companies come via the founders experiencing a deep personal pain, or sensing a problem in their personal experiences, and thereby starting a company to scratch this itch. This is U.S. data and based on what Lenny found in his investigations of successful startups in these segments. I did a study of 119 Indian unicorns (till Sep’24), and I found that ~60% of unicorns emerged via the pain or personal experience route. More details on the study here (additional supportings here). But if you tease apart personal pain and personal experience, you find that personal pain route was only a fourth of the combined share. See below.

If we look at consumer startups, then in the U.S., 30% of successful U.S. consumer startups originated via the personal pain route (Lenny doesn’t break up B2B that way, so we don’t have a similar number for B2B). The equivalent number for Indian unicorns (those that came via the pain route) is 15%. I don’t have a strong hunch for why there is a significant difference in these route shares for U.S. vs India.

Let us take some examples of how this route plays out

- Sneaker marketplace GOAT began when cofounder and sneaker buff Daishin Sugano got a pair of fake Air Jordan 5 Grapes from ebay. The reconciliation process was so painful, and the experience so disappointing that he and his cofounder Eddy Lu began talking amongst themselves about the problem. That led them to the problem of not having a reliable authenticated sneaker marketplace, eventually leading to GOAT.

- Tech founder + operator Sudheer Koneru got on a wellness and fitness trip, and decided to invest in a spa + salon chain in Hyderabad in Southern India. He later decided to run it full time, and then experienced the limitations of the existing spa and salon management software in managing a multi-outlet setup. He thus decided to build one instead, called ManageMySpa. Later, Sudheer sold the spa + salon chain and decided to focus full time on ManageMySpa. Subsequently after an investment from Accel India, this became the now well-known Zenoti (turned Unicorn in 2020).

Paul Graham calls these as organic startup ideas – “those that grow organically out of your own life.” He writes in his essay, ‘Organic Startup Ideas’: “Organic ideas are generally preferable to the made up kind, but particularly so when the founders are young. It takes experience to predict what other people will want. The worst ideas we see at Y Combinator are from young founders making things they think other people will want.” Paul Graham’s perspective as an investor tallies what I have seen in my years in venture investing too. In general, VCs have (relatively) more affinity to picks emerging from pain or personal experiences, especially for first-time founders. This doesn’t mean they fund more of this type but that they develop conviction faster if the founder resonates personally with the problem. Let me unpack this.

From the section on ‘What makes a great pick?’, we know that early stage VCs evaluate a startup for funding by asking ‘Why this?, ‘Why now?,’ and ‘Why you?’. The ideal startup would have compelling answers to these questions. Picks that come from a personal pain, answer the last question – why you? – successfully. It signals founder-problem fit or what is commonly referred to as founder-market fit, thereby indicating a higher right to win for the startup. This is because of two reasons:

1) the founder has arrived at the problem through a pain they experienced, and because they have wrestled with the problem personally, they have a greater understanding of the problem space, and they thus have an unfair advantage in coming up with solutions.

2) founders who are trying to solve their personal pain are also likely to stick with the problem and persist longer trying various attack angles. They are committed to solving the problem because of a personal mission.

A compelling example of a founder deeply inspired by a personal mission is Matt Rabinowitz of Natera. Matt, a Stanford PhD in Electrical Engineering, saw his sister’s baby die within a week of birth due to a rare genetic condition that went undetected during pregnancy. He founded Natera to ensure others wouldn’t have to face this issue. Sequoia’s Roelof Botha, who is on the board of Natera, says in a podcast interview: “…you hear him (Matt Rabinowitz) talk about the motivation for starting a company like that. It’s emotional. And you understand that this person is mission driven, and then you understand all the things that they did to uncover the nuances of why this is a problem they’re going to dedicate maybe the rest of their life to.” All other things being equal, a VC would prefer to back such ‘missionary’ founders, drawn to a problem by a personal mission, as opposed to say ‘mercenary’ founders who are looking at startups as a route to wealth creation.

How does one go about picking via pain or personal experiences? Is it something that you fall into? Something that just happens or as Graham says, “grows organically out of your life”? Is there a systematic way to arrive at a pick that reflects a pain or a personal problem? A systematic approach to organic problem discovery sounds like an oxymoron but there are some approaches or playbooks. We list a few in the next section.

2D.2/ How to ‘pick via pain’

Jared Friedman, previously cofounder and CTO at Scribd, and now Group Partner at Y Combinator, describes two approaches to organic problem discovery, or arriving at a pick via pain or personal experience. The first, better suited for B2B picks, is to mine your personal experiences, going through all the companies that you have worked at including internships, and asking yourself three questions

- “What are things that you learned there that other people don’t know?

- For each company, what seemed broken? What parts of company life were clumsy?

- Were there things that your company built in-house that other companies might need?”

He gives examples of startups that reflect these approaches. Snapdocs came out of Aaron King’s decade-long experience in the mortgage industry, Lattice came from founders Jack Altman and Eric Koslow seeing broken HR processes at their then workplace, Teespring. Mixpanel was founded by Suhail Doshi and Tim Trefren on seeing inhouse analytics tools built in their then workplace Slide, and understanding that other companies would need similar tools too.

A second approach suggested by Jared Friedman, and also encouraged by Paul Graham, is better suited for arriving at B2C picks, though it is also useful for B2B contexts. This is to build what you wished someone would build for you, essentially to solve a problem that you personally have. Paul Graham puts it well: “pay particular attention to things that chafe you”. Two examples:

- Hex, a collaborative data platform, was built when Barry McCardel realised that no one was building what he wished. He says: “I actually started this journey as a buyer. I was looking for something like Hex and I couldn’t find it. It took me a few months of going around and talking and asking people like, ‘Oh, what are you using for this? What are you using for that? Have you found anything good for this?’ Everyone said, ‘No, but if you do, let us know.’ It almost took us a while to be like, ‘All right. I guess we have to do this. Don’t we? No one else is doing this, while we have to do it.’”

- Dropbox originated when Drew Houston got into a bus for New York, determined to work during the ride, and found that he had forgotten to pack his USB stick / thumb drive, which contained the files he was to work on. “I was so frustrated because I felt like this kept happening,” he says. “I never wanted to have the problem again, so having nothing else to do… I started writing some code [to find a solution], having no idea what it would become.”

There is another approach too. Mike Maples, Jr., cofounder of Floodgate Ventures, writes in his recent book Pattern Breakers of how breakthrough insights come from living in the future, and building what is missing. Paul Graham has a similar line in his essay ‘How to get startup ideas’: “Live in the future, then build what’s missing”. Maples Jr., gives the example of Justin Kan, who launched Justin.tv broadcasting (or ‘lifecasting’) his life 24/7 sans time for bathroom breaks. Eventually Justin.tv would see it spin out into two companies, Socialcam (acquired by Autodesk for $60m in 2012) and Twitch (acquired by Amazon for $970m in 2014). Clearly, Justin Kan (and his cofounders) was living in the future, and he built Justin.tv because it was missing in the future. His next most ambitious project was legaltech startup Atrium, founded in 2017, and funded to the tune of $75m, but failed to achieve PMF and shut down in 2020. A key reason for its failure, says Maples Jr., is that Justin Kan had no real passion for the space, that is, he wasn’t living in the future where Atrium (or its legaltech offering) would be a missing solution.

Justin Kan describes it well in a blogpost: “I decided to leave YC and start another new company. This time, I settled on the concept in the most mercenary way I could think of: all I wanted was to create the biggest possible company. Once again, my dreams were full of insanely large numbers. A ten-billion-dollar company. A hundred-billion-dollar company!” (Notice the use of the word ‘mercenary’ by Justin, the opposite of the ‘missionary’ mindset which I had referred to earlier). Genuine interest and passion for a space matters, for the startup journey isn’t going to be easy, and without the passion for the space and the problem, the founder won’t survive the arduous journey. Dylan Field, cofounder of Figma, agrees: “… find something that you are personally passionate about, because any good company takes a long time to build. If you are, let’s say, three to four years in on an idea that you hate, you’re just going to burn out and you’re going to quit. … go for an idea that you really care about, because even if it doesn’t work, you’ll still learn from it and you’ll still have one.”

That said, while passion helps, it is not integral to startup success or even product market fit. It does make the journey easier though!

2D.3/ Validating the ‘pain pick’

As I shared in the earlier section, validating the problem / pick is done via a combination of secondary research, looking for proxies of potential, and conversations with potential users or customers. Let us look at some examples of problem validation here.

- Webb Brown and Ajay Tripathi, co-founders of Kubernetes cost monitoring tool Kubecost (acquired by Apptio / IBM) spent two months interviewing teams at about 120 different companies to validate that the lack of transparency in pricing, resulting in millions of dollars in cloud costs, was a key pain point for Kubernetes users. Those conversations helped “inform, tweak and fine-tune the shape of their solution. At that point, we said, ‘OK, there’s enough here to where we want to really start thinking seriously about what a real product would look like.’” While conversations help, you can also quickly get proxies or signals to validate user or customer interest in the problem.

- Ritu Narayan, founder of Zum, gathered feedback for an early avatar of Zum, a B2C offering called Liftee (enabling safe rides for children) by sending out mock artifacts. She says “We emailed Liftee’s mock website to a Palo Alto parents group with messaging along the lines of, ‘be a parent, not a chauffeur.’ Within 24 hours, we had over 300 interested parents.”

Some founders validate the problem, and understand the contours of it, by doing a lot of secondary research. Airtable’s cofounder Andrew Ofstad says: “We were intellectually excited about going down that path of this general space of software creation. So we spent a lot of time doing research. It was almost like being on a sabbatical, reading all this prior art of old computing pioneers, like Douglas Engelbart and Bill Atkinson, and even contemporaries, like Bret Victor. We played with old products, like HyperCard, that had flavors of software creation for everybody, and read a lot about how to visualize complex systems.” Andrew feels that it is only thanks to this ‘long gestation period’ of reading and exploring, and “examining the problem from every angle” that they were able to get a high level of motivation and conviction required for a “horizontal product that’s pretty hard to market and has a lot of stuff that needs to be built to get to MVP.

An innovative way to get problem validation for a pick comes from Ryan Petersen of Flexport. To validate his pick, which was about making it easy for customers to manage trade regulations around export and import like customs duties, he “used Photoshop to create screenshots that looked like a real app. He put them up on a website to see if people would sign up for this fake product and used SEO and Google ads with a small budget to drive traffic to the page. Over 300 companies (including Saudi Aramco!) signed up for Ryan’s fake company, which gave him real validation that there were at least hundreds of companies who would want this if it existed.” He then conducted phone interviews with those who signed up to validate that the problem was real, and these signups were desperate for a product that would make trade and life easier.

To wrap, reach out to prospective customers, i.e., those you think have the problem you are looking to solve, and validate that it is real and big. What you are really seeking in this phase is the depth and extent of the problem. How many conversations is good? Well, I recommend 10-15 every week totalling to about 50 conversations in a month. At the end of the month you know if the problem is real or not. Remember you need strong signals, so if it is not a hell yeah, the pick isn’t right.

2D.4/ Problem validation can also help you narrow down the problem

Problem validation here can also help the founders understand the space in more granularity and help narrow down to a sharper sub-problem within. Here are two examples of how the validation process helped two startups:

- The founders of product prioritisation tool Productboard, Hubert Palan and Daniel Hejl, were determined to build in the product management space, and conducted over 1,000 interviews with product managers and leaders over the course of a year (though some were problem validation interviews too).

- Felicia Curcuru, founder of foster / adoption care software Binti, spent four months shadowing San Francisco county’s child welfare team “watching them do their work, struggling with 70-column excel spreadsheets, and listening to their challenges”, to narrow down the specific sub-problem she wanted to pursue – giving better tools to social workers trying to place children with families.