Strategy is amongst the most ill-used terms in business. Its ill-use is, if anything, even more pronounced in the startup world. There are multiple reasons for that. This essay won’t cover those reasons; that is for another time. Instead, this essay will suggest a universal definition for strategy, and relate it to the startup landscape. I will also share how strategy interacts with the concept of culture, another ill-used term. The objective, then, of this piece is to create a common vocabulary around these topics, so we can start building on them, instead of constantly debating their meaning.

My definition of strategy

Per me, strategy is a set of interconnected choices, including intentional tradeoffs, that reinforce each other to give you a competitive advantage (relative to your peers) in the marketplace. Now, while this phrasing is distinctive, the concept of strategy as choices isn’t entirely unique or mine. I have adapted it from the definition suggested by Roger Martin and A.G. Lafley in their book ‘Playing to Win’, which to my mind is the best book I have read on strategy.

The choices that you make in arriving at your strategy are primarily around two elements.

- Where do you play?

- How do you win?

In Martin and Lafley’s definition, they add three more elements – winning aspirations (purpose, essentially), capabilities, and management systems – in addition to the two above. I prefer the simpler two-element choice set, because the first part ‘where do you play?’ subsumes ‘winning aspirations’ while second part ‘how do you win?’ is a reflection of the capabilities and management systems that you deploy. Additionally, because startups are still evolving and early in their journey, capabilities and management systems are nascent, and do not matter as much as in a larger well-established company.

Let us get back to the two choices – where to play, and how to win.

Where do you play?

‘Where do you play?’ (Where decision) is more important than ‘How do you win?’ (How decisions). ‘Where’ is a function of your resources including your (personal) preferences (basis your aspirations), as well as the tailwinds, and nature of the industry (is it very fast-changing, the size, the margin structure etc.).

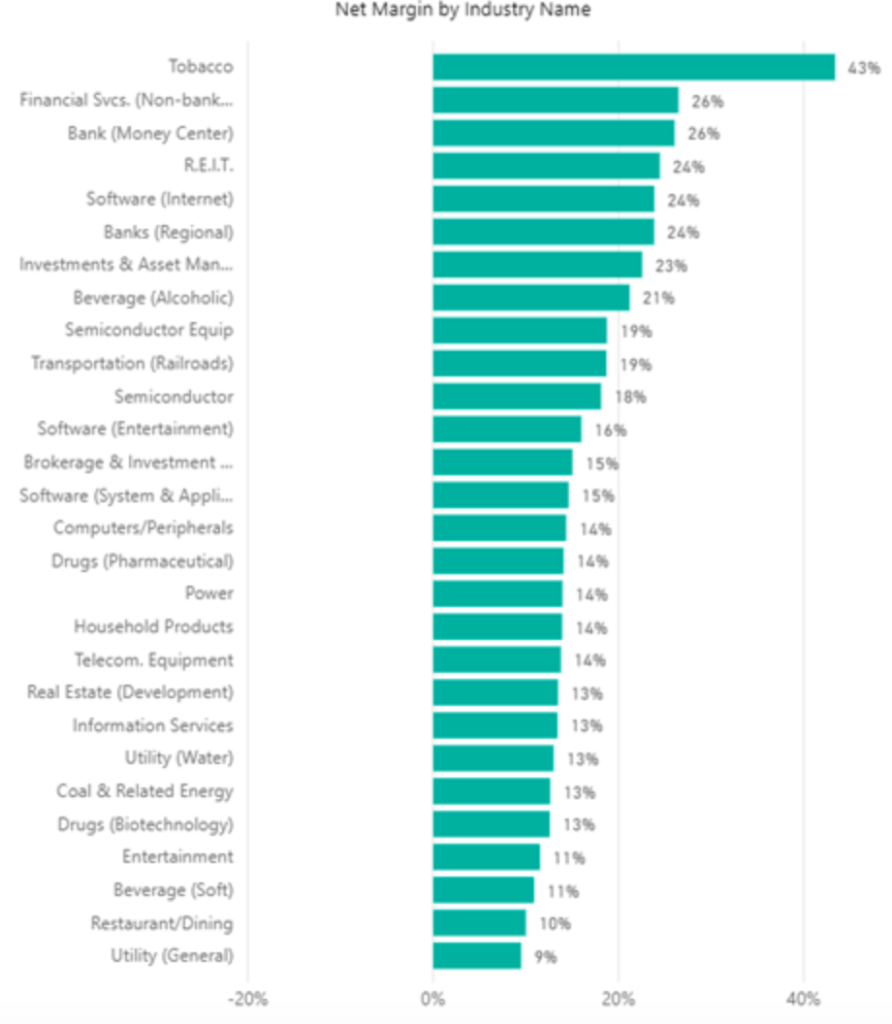

If you think ‘where’ doesn’t matter, then look at this chart (sorry for the poor image clarity) which ranks industries by net margin (effectively profitability).

Source: https://financialrhythm.com/profitability-margins-industry/

Each industry is governed by a powerful set of structural forces that determine the margin structure. The best-run utility will not make as much margins as the worst-run tobacco company. The best-run airlines will struggle to get better margins than a mid-range pharma company.

Here is Warren E. Buffett, from the 2007 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter “The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favour by shooting Orville down.”

Where you play, thus, matters.

For startups, the ‘where do you play’ decision is if anything even more important than for their bootstrapped counterparts. This is because of the way in which startup financing occurs, in a staged manner, by different funds, with clear (or so) milestones to hit for each financing round. A wrong decision on ‘where to play’ can have immediate consequences in making it hard to hit product-market fit fast, and making it tough to raise the Seed or Series A round.

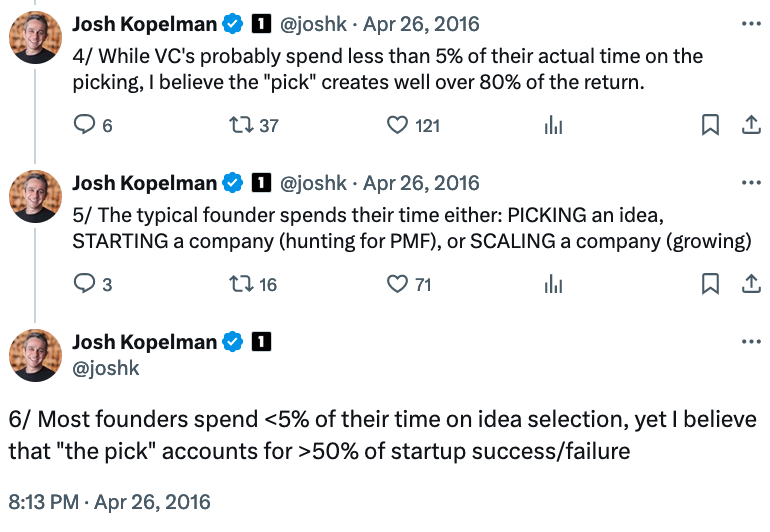

I remember reading this tweet thread by Josh Kopelman on what he calls the pick, and how both VCs and founders spend much less time on the pick, but it generates much of the value.

The ‘pick’ is effectively the ‘where do you play?’ decision. It is about the problem space you are choosing to work on, or the market that you are after. When you select the problem space, what you want to do is pick one where there is deep customer pain, articulated or unarticulated. You also want to pick a large space / market as well, but often you don’t really know how big the space could be till you have started building the product.

Occasionally, I meet with startup founders, who are very early in their journeys, to brainstorm on their ideas. Sometimes they want a reaction from me to their startup idea. A concept I share is that they should pick an idea that has a slant in it. One where the ball rolls downhill, not uphill; where the energy expenditure on evangelising should not be very high. These are ideas / products that are differentiated from the existing ones, and which are hopefully, as Kunal Shah says, Delta 4 compared to the existing solution. Even if not Delta 4, they should at least be Delta 2, else you will struggle to get the audience to shift to your product, or try it without high marketing costs.

How do you win?

‘How do you win?’ consists of all of the tactics and processes in your competitive playbook. It is about how you will reach and serve the customer in a cost-efficient manner, and on a sustained basis. This is best understood as your business system. Every business system, however effective also needs an aligned capital structure, and a financing playbook, i.e., how you will finance your operations.

Your business system consists of four parts

- Product

- Revenue model

- GTM / distribution

- People

All four parts of the business system need to be tightly aligned with each other. These are, the product you are taking to market, the revenue model in place that determines how your customers will be charged for the benefit they derive from it, the approach you are taking to get the products in the hands of the customer (Go To Market or GTM), and finally the people building the product and taking it there – the four mechanisms of the startup org / machine.

A top-down (go to market) motion typically has a strong sales team for outbound activities. Such a motion will often mean some customisation of the product for the customer, and that means the product team will have to adjust to the needs of the market. The revenue model may need an onboarding charge (to cover the cost of customisation and training requirements) in addition to the usual usage-based charge. Finally, the nature of the product, customer interactions and revenue model implies that the sales team will have primacy over the product team, and that it will be a sales-led org.

This will invert for a bottom-up model like that of a Postman, which will be a product-led org, an inbound GTM (led by SEO, referral, ads), a minimal sales team, which usually kicks in when you have reached some scale of product adoption amongst the user base of a company, and a freemium revenue model.

A top-down motion where there is a dominant product org (or vice versa) can be a recipe for disaster. A usage-based model applied early on in a bottom-up model can kill speed of adoption. A freemium approach to pricing for a top-down model leaves a lot of money at he table. Thus, the more aligned these four aspects – product, revenue model, GTM, and people – the more chances of an efficient business system. When you arrive at a reasonably settled and efficient business system, by now you also have an estimate of the market size (as I shared in the earlier section, the market size often only reveals itself when you have the product in motion).

Now to capital structure. Every business system, at least until it becomes settled and churns out free cash flow which can be reinvested into the business, needs a financing mechanism. In the startup world, that is venture capital (or [venture] debt, or revenue-based financing etc.). Ideally the quantum, and expectations embedded into the financing (say venture capital) needs to be aligned with the business system, and the market size. One of the big issues or non-alignments I have seen in India, is that the financing quantum (that is fund investments) and expectations, are not aligned to market size and the business system. Too much money is invested into the startup, and often because the investments are being done as much to solve a capital deployment problem for the late growth investors.

What this leads to is far too much money invested into startups whose effective market size is just 30-50m households. There are startups who do have a larger TAM (like Amazon, Flipkart, Paytm) but they are few in number. Most Indian startups have a TAM that is limited to India1. The investment into them however presumes they all have India TAM.

What the increased (investment) and spending does is that it leads to a different GTM motion than before, and often a different or expanded product (to cater to a wider market), leading to a misalignment in the business system parts. Successful Indian consumer players like HUL, Asian Paints, Titan, HDFC Bank, have all grown with the Indian consumer, never ahead of them. Most Indian startups, stuffed with capital, and weighed down by the expectations of growing fast to justify that capital, are investing ahead of the consumer.

Byju’s is the canonical example of the above, raising an almost inexhaustible corpus of capital, and that led to a rapid disalignment of the parts of the business system. It had product-market fit (PMF), but the additional capital and the rapid disalignment of the business system meant, it lost this PMF.

One way to define PMF is that it is achieved when you can continue to increase capital in the business without it dis-aligning the elements of your business system. That is, more money can be raised and deployed, without the product, GTM, revenue model and people elements, getting out of sync with each other.

So, where does culture fit in?

Culture, incentives etc., are all effectuating mechanisms for strategy. ‘Effectuating’ is an ugly word, I know, but it is effective here for describing mechanisms through which strategy is implemented or brought about. Let us look at how a decision can be taken. Obviously the most effective way is for the founder / CEO to take it. However, this is inefficient, in that there is no leverage. Each time the founder / CEO has to be involved to take the decision, and this will put a rate limiting factor on the number of decisions.

The next better way is to put together a rule book with clears dos and don’ts. This is better as it lays down clearly what can and can’t be done. It is also high leverage, but the challenge is that it is not comprehensive; it will never cover all edge cases and hence in those situations you can come back to the founder / CEO. The other challenge is that it covers the basic minimum action, but it won’t cover the intensity of action, e.g., how much effort to put it in, how extra a mile to go.

Here you can try incentives, typically financial incentives. If you set the incentives well, and cover both quantitative and qualitative (check metric) measures, and these are aligned to your business systems and goals, then you have something which is high leverage, and reasonably comprehensive. It still won’t cover certain edge cases like certain kinds of customer complaints.

And for that, you need culture. Culture is ‘how your company makes decisions when you aren’t there’ (Ben Horowitz). Culture operates the highest level of leverage, and comprehensiveness. Because it needs to be perceived and applied by each person who needs to grow into your culture, and often their actions can’t be monitored, or outcomes seen till later, the feedback from culture can take long. But is the best and ideal long-term way to drive desirable actions in the organization and to build high alignment within, as well to effectuate your strategy.

All organisations will see different combinations of these tactics. In one, culture may have a large surface area; in another co, rulebooks may have a larger span. Again, culture in and of itself is not necessarily good. Some cultures may tolerate fraud, bullying, restrict innovation etc.

The following chart is a good way to absorb the above effectuation tactics, at one glance

| Effectiveness | Leverage | Comprehensiveness | |

| 1:1 meetings | Highly effective | Low leverage | Covers all cases |

| Rulebook | Effective | Higher leverage | Can’t cover all cases |

| Financial incentives | Mostly effective | Moderate to high leverage | Cannot cover most cases other than revenue generation well |

| Culture | Mostly effective | High leverage | Covers most cases |

Wrapping up

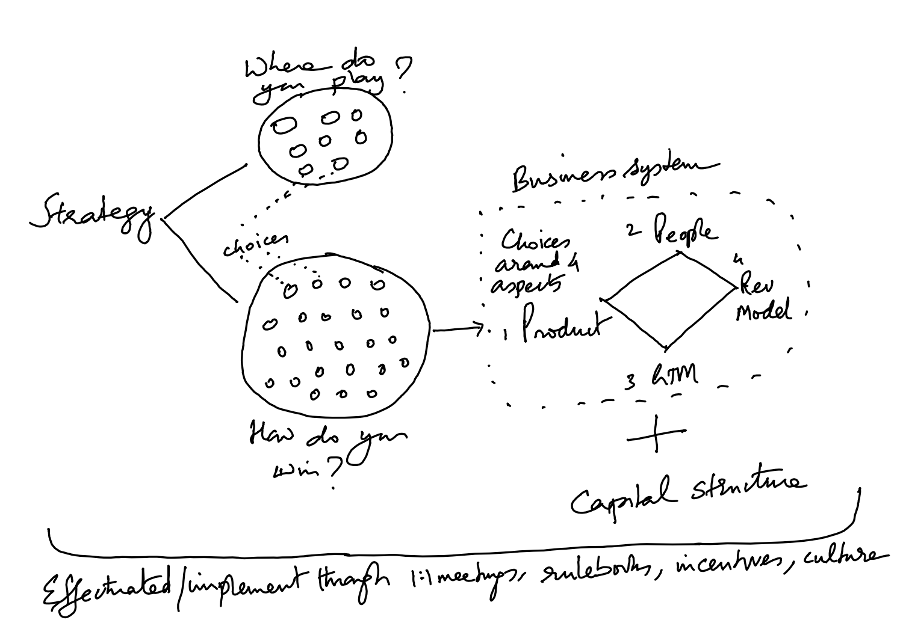

Good strategy is arriving at a set of interconnected choices and intentional tradeoffs that reinforce each other to give you a competitive advantage. These choices and tradeoffs fall in two buckets – ‘where to play?’ and ‘how to win?’. The latter in turn breaks into four business system elements (product, GTM, rev model and people) and the capital structure. All of these elements make up strategy. This is effectuated or implemented through 1:1 meetings, rulebooks, incentive and culture.

Here is a terrible drawing that aims to capture the above.

If I could leave you with three concepts from the above, it would be

- Strategy is about choices and tradeoffs

- The most important choice is around where to play

- A winning business system needs to be married with the right capital structure, to arrive at a solid how to win.

***

I hope you found this interesting. You are welcome to share questions / feedback / criticism at sp at sajithpai dot com (No pitches please here; i wont respond to them. Do note that replies to questions / feedback / criticism may take anywhere from a few mins to a few days. It depends on what I am doing then, or my state of mind, or the energy required to absorb your mail, or the length of response demanded, or some or all of these!)

April 5, 2024 @ 10:54 pm

I especially liked the point about considering resources, industry, and customer pain points when making these decisions. It’s important for startups to be realistic about their capabilities and to focus on a market where they can add value.

May 12, 2024 @ 4:02 pm

How does one know if your product will be a top down or a bottom up motion?

May 13, 2024 @ 9:12 pm

It depends on the ICP and how they like to purchase. If you are selling a B2B product, and if anyone in the org can sign up for it with a credit card, then it is bottom up (Notion, Figma all fall in this bucket. Else it is top down, where one authority the CIO or CRO or CMO negotiates and buys for the entire org, like Okta or Salesforce.