[This was written in late ’20, and I had posted it as a Notion page. Now consolidating all of these reviews posted elsewhere into this site.]

Published 2020. 293 pages. Read Oct’20. If you see ‘SPW’, that stands for Sajith Pai’s Words, essentially my comments and marginalia.

The book describes the unique culture at Netflix, one that Reed Hastings (Netflix’s CEO and cofounder) says has been instrumental in its long-term success and reinvention from an online US DVD rental purveyor to a global live streaming provider. The book is written by Reed Hastings w Erin Meyer, a professor at INSEAD business school and author ‘The Culture Map’. Unlike a traditional co-written book, this one is structured a tad differently. Each chapter consists of several alternating short passages (2-5 pages) written by each of them, sharing their perspective on the same topic. It is an interesting format that doesnt jar thankfully.

At a high level, the book says that the Neflix culture OS (SPW) consists of 3 coupled features

- high talent density; with average talent actively weeded out

- a culture of frequent candid feedback, that is codified and ritualized

- few controls and policies such as reimbursement, vacation etc. and instead stressing context over how an employee should act, than institute control

The book deals with how Netflix arrived at these 3 features, and how they implement them at Netflix.

The book is structured thus:

- 3 sections of 3 chapters each: In each section, one chapter each on one of the above features. The first section is about taking baby steps, so each chapter covers the basic steps you need to institute. The second section is about going full bore, and the chapters again deal with the above 3 features but on advanced steps. Finally the third is about reinforcing and maintaining these features or elements of the Netflix culture OS.

- 4th section – 1 chapter on how they adapted the above 3 features to different countries as they expanded globally.

- The sequence of the chapters is the order in which the concepts in the chapters were discovered at Netflix

My view on reading the book is that this OS developed over a long-period of time at Netflix, and has thus got stress-tested and proofed over time. The full bore version of the Netflix culture OS is not suitable for all companies and cultures. It also isn’t easy to implement given that change needs to be driven from the top, and I cant see too many CEOs being as receptive to feedback as Reed Hastings is. That said perhaps a weak or diluted version can be incorporated – specifically those ideas mentioned in the 1st section. A fuller version is I feel better suited for well-funded and established startups that are in the 5->10 phase of the journey (and not those in 0->1 or later phase). Overall, a good read though with limited applicability of most concepts beyond larger well-funded startups.

Let us dive into the book and take a look at the 3 features, and how Netflix developed and implemented them.

Talent density

Something special happens when the amount of supersmart non-jerk high performers cluster. Hastings refers to them as ‘stunning’ colleagues. The organization becomes an exceptional place to work. There is increased efficiency, as there is fewer need to work around mediocre people. the lowest common denominator now now tracks higher. There is also increased competitiveness of the good kind, as high performers get motivated by other high performers. One point to note is that Neflix has a ‘No brilliant jerks’ policy.

We underestimate how much a mediocre person can bring down performance in a team. Also tolerating mediocre people is a clear sign to everyone that excellence is not valued; this can encourage high performers to leave.

For Hastings and Meyer, the first step or the most critical dot towards a high performance culture is increasing talent density – this means both hiring high performers and not tolerating low performers. Having a lean team of high performers is easier to manage than a bloated mixed team of high performers and average folks, says Hastings.

Netflix ensures hiring of high performers by paying top of personal market salaries (top of the market for that person’s job and skill set in the geography they are hired for) to attract them, and by ensuring high performers continuously earn top of market. Employees are encouraged to take recruiter calls and find out what their value is! Managers too estimate what other companies are paying for such talent (by calling their peers in other companies) while determining salary raises for their team members.

One important distinction that Hastings makes is between operational roles (driver, maintenance man) and creative roles. The best cleaner can at best do 2x (usually not even that) output of the average cleaner, but the best script buyer can generate 10-100x the output (revenue) of the average. Given this, he suggests that you could divvy your team up into operational and creative roles and focusing the top of personal market payment policy on creative workers.

It is not just what you pay; it is also how you pay it. At Netflix, salaries dont have a bonus component. Contingent pay works for routine tasks but not for creative tasks, says Erin Mayer.

One interesting point that Erin makes is that a lot of the traditional salary-planning frameworks such as raise pools and salary bands are reminiscent of an era in which manufacturing was centre-stage. As we move towards a world where creative thinking rules, and one person can single-handedly make a difference / do the work of 2-5 other people, then we need to rethink these concepts.

Family is not a good metaphor for a high-performing talent dense workforce, says Reed. Instead a better metaphor is a sportsteam. Members of the team have their focus areas, but they also have to work with each other for a common goal. And yes, if you dont perform, then you can be removed.

The ‘keeper test’ is one way Netflix ensures that they maintain talent density. It encourages every manager to ask themselves that if employee X were to quit tomorrow, would they fight to keep him or her? If the latter then Netflix policy is to retrench this person with a generous severance package (4-9months) and look for a star. Executives can prompt their manager with the question “If I were thinking of leaving, how hard would you work to change my mind?” This is the keeper test prompt, he says.

One interesting point. Reed says you have to remove any shame for anyone let of from Netflix. It is like being let go from a top sports team. You have to be awesome to make the team in the first place, he says. In this regard, he mentions Patty McCord, the long time Head of HR and Leslie Kilgore, the long time Head of Marketing as examples of old timers who grew out of the role.

2 usual practices that Netflix doesnt do

- stack-ranking / bell curve: as that encourages internal competition and discourages collaboration. There are unlimited spots on the Netflix ‘sports’ team unlike the traditional sports team, Reed says.

- performance improvment plans: keeping a mediocre person on for another 4-6months is costly. It is also humiliating for the person. Instead take all of that money and give it to the employee in the form of a generous severance.

SPW:

- Since there is a high cost of firing, and firing ‘non-talented’ or average folks is a key part of Netflix’s culture, it is worth understanding if Netflix sources talent differently from the market, or runs the interview process better to make sure they select high performers. There is nothing on this in the book. Seems a key gap. Also if someone hires wrong consistently isn’t there a penalty? (do keep in mind that a person may do well for 2-3 yrs and then do badly after promoted – so this needs to be weighed in).

- Paying top of market salaries is clearly one way to attract the best talent.

- All of the above works only when you are well-funded and / or profitable. In absence of this condition, not easy to pull off this policy of paying top of market salaries.

Candid feedback

Netflix is big on frequent, candid feedback. They use a framework that Erin Meyer calls the 5A framework.

- The feedback should aim to assist. Dont give feedback to take something off your chest, or to hurt the person. The goal should be to help the person, and Netflix.

- e.g.., “the way you pick your teeth in public is irritating.” is wrong. The right one is “if you stop picking your teeth in public, you will be seen as more professional, and it will help the company too”.

- The feedback should be actionable, such that the recipient can take corrective action on.

- The recipient should appreciate the feedback; senior folks receiving feedback should appreciate negative feedback publicly and acknowledge it. Show ‘belonging cues’ – public appreciation of even negative feedback. This shows that there are no consequences to giving negative feedback to seniors.

- Seniors, once you have demonstrated competence or track record, when they talk openly about their mistakes and failures, leads to increased trust, goodwill and transparency in the org.

- It is up to the recipient to accept or discard the feedback. You are required to listen to the feedback and acknowledge the receipt.

- adapt the feedback mechanism to local culture such as more formal feedback mechanisms in indirect cultures (Asia)

Give feedback publicly if the feedback can help the person there.

Netflix is huge on transparency internally. Everyone knows confidential financial data and there is no hiding of internal metrics that in many other peer companies is kept secret. That said the penalties for any transgression is very high.

One interesting point that emerged is the tendency to overshare even when it can cause undue stress to an employee like telling a colleague in advance if her division might be yanked, even if the chances are only 25% etc. While publicly talking about a learning incident, like a sacking or harassment, then Netflix encourages open conversation. But if the incident is a personal one (like a alcoholism issue), then Netflix encourages people not to talk publicly and to speak to the concerned person directly.

Feedback culture is codified at Netflix through 360 reviews – both written (non-anonymous) and live. Performance reviews are too one-way.

- Written 360 feedback is annual and each person gets from at least 10 colleagues. 30-40 is not uncommon for senior folks.

- At Live 360 dinners, they use the Start, Stop, Continue method with 25% positive and 75% developmental feedback. All feedback is actionable with no fluff.

Context over control

Netflix has no travel policy! Its reimbursement policy simply says “Act in Netflix’s best interest.’ (this was iterated from ‘Spend company money as if it were your own’ after too many people started being untowardly frugal).

Netflix encourages managers and leadership to set context for each control that is removed. In the case of vacation, it is senior leadership taking long breaks and then talking about it publicly, and also asking others where they are going? Otherwise a ‘no vacation policy’ becomes a ‘no vacation’ policy!

In the case of reimbursements and removing any expense control, they do encourage managers to talk to their team on what is actually in Netflix’s best interest and what isn’t. Set context. Also, if they detect any abuse or transgression, to sack the employee to make an example of it.

Reed says some expense will increase with freedom. But the costs from overspending are outweighed by both the gains that freedom provides as well as the savings of finance and procurement teams put in place to oversee the controls.

Reed also says that many employees will respond to their new freedom by spending less than they would in a system with rules. When you tell people you trust them, they tend to be more trustworthy.

Decision-making at Netflix is dispersed across the workforce. There is significant freedom to take a call. A few guidelines hold, of which the most important is “ Don’t seek to please your boss. Seek to do what is best for your company.”

At Netflix, decision-making and especially decisions on new, big ideas are delegated to the person driving the initiative. After all you paid top of personal market to get this person. So ensure that you give her the complete context, and then leave her to make the judgement. Then, trust her judgement and move ahead. The more the boss moves out of the decision approver role, the entire business speeds up and innovation increases.

Netflix states this philosophy as ‘lead with context, not control’. Control is fine in mission-critical highly operational roles (manufacturing, medicine etc.) but in creative professions, where innovation is the goal, the risk is not making a mistake but becoming irrelevant, because your employees are not coming up with the best ideas.

As Antoine de Saint-Exupery puts it, ““If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.”

Highly aligned, loosely coupled is a mantra at Netflix. Loose coupling refers to decentralized decision-making. High alignment refers to the clear, shared context between the leadership and the team.

Reed says: when one of your team members does something dumb, dont blame them. Instead ask yourself what context you failed to set. Did you share the common goals and strategies, the assumptions and the risks, that will help them make good decisions? are you and your employees highly aligned on vision and objectives?

Erin introduces the metaphor of pyramid vs a tree to contrast centralized decision-making at companies such as Disney with the decentralized approach at Netflix. Reed at the roots, holding up Sarandos on the trunk which supports the outer branches where local executives take decisions.

The Netflix innovation cycle works thus.

- Take your big idea and ‘farm for dissent’ – actively seek contradictory views and in that process socialize your idea. Farming for dissent is one of the important (though few) processes at Netflix. This is done via seeking views and comments on a public note. The manager seeking views is not mandated to use the feedback, but it constitutes important feedback. At Netflix, after the Qwikster mishap, it is now considered disloyal to the co if you disagree with an idea but do not express it.

- For smaller ideas, it is considered ok to socialize the idea with multiple stakeholders and get a temperature check. The objective here is more farming, than seeking dissent.

- Test out the big idea

- As the ‘informed captain’, place your bet. At Netflix if you are the owner of the initiative, you take the decision, you sign contracts, send out purchase orders etc.

- If it wins, then celebrate it; else do the following

- ask what learning came from the project

- dont make a big deal about failure – else you’ll shut down all risk-taking

- ‘sunshine it’ – address the failure publicly and share learnings from the failure. It is important for employees to keep hearing about the failed bets of others, so they are encouraged to take bets (that might fail).

- SPW: similar to M&Ms (morbidity and mortality conferences) in medicine. (Complications by Atul Gawande pgs 49-56 covers this)

To wrap this section, the Netflix OS eschews traditional policies and controls such as vacation policies, reimbursement policies, KPIs, bonuses, conract signoffs by senior people, salary bands etc. Some are schewed because they slow decision making or reduce speed of movement, some because they introduce rules and controls that hinder innovation and initiative. If you want to build an agile, innovative org, and develop a culture of freedom & responsibility (as they term the Netfilx culture OS), then you can remove these rules and processes as Netflix has done.

Going Global

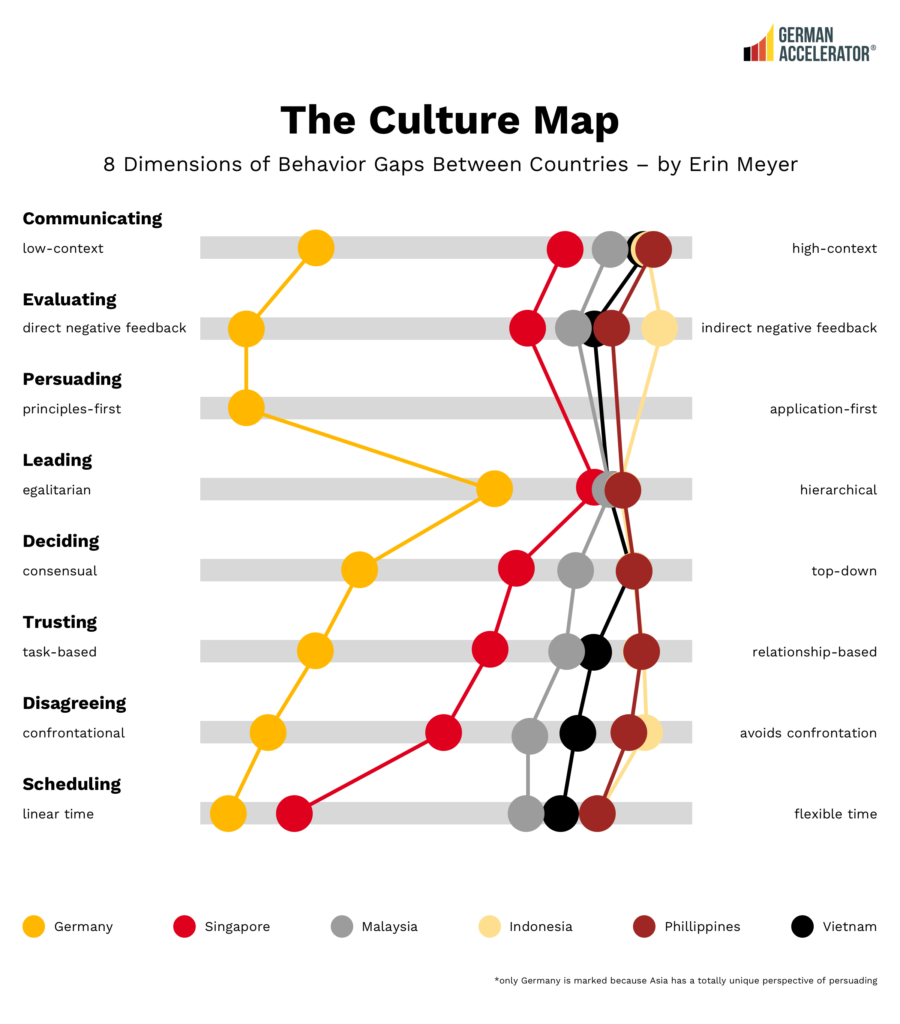

In the last chapter, Reed and Erin explore the ramifications of going global, and how they had to adapt the Netflix culture to local hubs. The chapter describes how Erin’s book The Culture Map was used by Netflix to map how Netflix’s culture of Freedom & Responsibility contrasted with the culture locally.

A big learning was to implement more formal feedback mechanisms in countries where direct negative feedback (especially Asian countries) is uncommon. And in more direct cultures, talk about the cultural differences openly so they understand how to tailor messaging outward to more indirect cultures.

The Culture Map looks like this.