This is a long post. Microsoft Word puts it at 4,542 words! Possibly the longest I have written. It explores a diversity of ideas and themes: a moniker called MERIT colleges to replace the inelegant IIT / IIM we use to earmark an elite college in India, the emergence of two parallel tracks of merit, a national consciousness that elite Indians share, and finally their privilege blindness. I hope you will forgive me for the length of this essay. If you do get to the end of it, then I would love to hear from you on the essay and what you made of it.

***

“Such a small world!”

I remember a passage from a book, or perhaps a magazine I read long ago, about a U.S. college student talking about his fellow French interns. The gist of his account was that all of the French interns he encountered seemed to know each other from before, or knew someone in common in the colleges they studied back in France. The U.S. student found this unusual for he felt U.S. college students rarely had such an intensity of common connections. A key reason they knew each other, he thought, was because unlike the U.S. students, the French largely went to a narrow set of elite colleges (called The Grande Ecoles; a wonderful explanation of the French educational system by Nicholas Colin is here).

There is a clear parallel between the French and Indian elite students in this regard. And when I say elite Indian students, this extends beyond IITs / BITS / NITs to other selective engineering colleges such as Manipal, VIT, PESIT, or even the National Law Schools, Ashoka, city colleges such as SRCC, St Xaviers etc. Bring together two Indians who went to any such selective college, and invariably they will find a common connect.

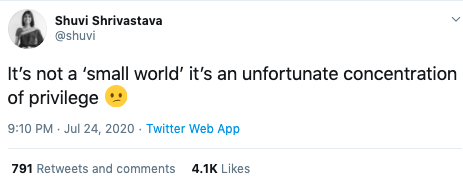

It helps that these elite Indian students are mostly from a narrow sliver of the Indian student body. If we estimate that there are about 175-200k (see endnotes for how I arrived at it) students entering these elite Indian colleges annually, then remember that almost all of these elite students come from a base of ~3.5m students graduating out of English medium schools annually in India, or an even smaller sliver of the 1-1.5m graduating from the English medium national board schools such as CBSE / ICSE (see endnotes for the calculation). I would hazard that about 3-4,000 schools spread across the top 30-40 cities in India will account for as much as 75-80% of these 175-200k students. This explains why elite Indian students find common connections far easily. In that regard, this tweet is telling.

Unlike the French with their Grande Ecoles or U.S. with its Ivy League moniker, there is no equivalent convenient moniker in India for top tier or elite colleges. You often see IIT/IIM as a catchphrase for such colleges. Sometimes this is expanded to IIT/IIM/BITS or IIT/NITs/IIM as the case may be. I find the IIT/IIM catchphrase odd because IIM is a post-grad college exclusively (barring IIM Indore which has an unusual 5yr BBA+MBA program). In addition, it is an inconvenient moniker one as it uses a specific set of institutions as a catchall phrase for elite colleges. You are never sure when it refers to those institutions only, or when it refers as a moniker. Given this, we need a term that better describes or serves as a catchphrase for top tier colleges in India. I will put forth my proposal soon in this essay, but to get there I want to begin with the following components or characteristics of the elite Indian college, and use that to explore Indian society.

MERIT colleges

I see top tier colleges in India (or even abroad) as having the following distinct characteristics. They are –

- Tough to get in to or have a high selectivity in intake: Less than 10-20% (in many cases <1%) of students who apply get in to these colleges

- Either based in a Metro and / or is Residential in nature: Elite colleges are usually residential in nature, the exceptions being SRCC / St Xavier’s and their ilk located inside a Metro. These have a mix of day scholars and boarders. There isn’t a single elite college in a city that is attended only by day scholars. And similarly outside of the top 7 metros, there isn’t a single reasonably well-known city-based college, with a large day-scholar population.

- National / All-India intake: the student body is from across all states in India. There may be a skew towards certain regions (specifically metros) but on the whole there isn’t a single region that is not represented (The North-East typically gets the least representation).

- English-fluent students: Graduates of these institutions are fluent in English. Not all of them speak perfectly but almost all of them, if not all of them, do written English well, and are conversant with aspects of Western culture.

You can look at any college that is considered top tier or elite in India, from the IITs to Xaviers in Mumbai or Ashoka University, and you will see that they tick these four boxes – of selectivity in intake, students from all across India (national intake), presence in a metro or residential nature, and English-fluency.

Some of these features correlate together – colleges that are tough to get in to and are highly selective see a national intake; these are highly desired institutions and seen applications from across India. So does residential with an all-India intake, as students coming all across from India need a safe place to stay. It is hard to think of an elite institution in India that does not tick these boxes. And I will say even the converse – that if you do not tick these boxes, you will not be seen as an elite institution in India.

The best I could come up with, using the first letters of Tough to get in to, Metro / Residential, India-wide intake and English-fluent, was MERIT schools or colleges as a moniker for these colleges. This is of course a pun on the word ‘merit’ which in India, has come to take on a very different meaning from its origins. MERIT colleges thus comprise not only IITs and BITS but even VIT, Manipal, PESIT, Ashoka, Shiv Nadar U, the National Law Schools, and even colleges such as NID, Srishti, St Stephen’s, Xaviers etc., any college that is selective, sees national intake of students and is residential in nature (or has facilities for boarders) and sees people like us, or the kids of PLUs, graduate.

IIT and VIT

It is admittedly, surprising for many to see a VIT (Vellore Institute of Technology) and Srishti in the same league as an IITB or SRCC. And some of you may accuse me of stretching the borders of the top-tier category a bit too much. I would disagree. My arguments are of course based on my lived experience i.e., from my interactions with graduates of these colleges with whom I have interacted in my corporate and personal life. And I haven’t seen any markedly distinguishing qualities in these students. You are entitled in your criticism to say that I have only interacted with a narrow set of students from VIT or PESIT, and specifically those who have selected themselves into the circles I move in. Essentially that these students are the winners and I shouldn’t judge the entire college basis a set of winners.

That is fair, and in my defence and those of the students from VIT, PESIT etc., all I would say is that the decisive advantage given by an exceptional performance on the IIT JEE (Joint Entrance Exam) has started declining today. In the 60s-90s when information asymmetry was rife, when the internet didn’t exist, IITs/BITS conferred a decisive advantage – of access to resources and opportunities. Today you can build your profile by creating, building, writing, interning and this can be done independent of the institution. Heck, you don’t even need to go to college today to do all of the above and build your personal brand. Thus what the internet has done is to disturb the career path dependencies that arose or occurred due to performance on one exam, like the JEE.

Still, then why do colleges matter, and why does a VIT score over a tier 2 engineering school in Madurai or Meerut? Why not then extend the MERIT tag to every college in the country? Well, I do think a certain minimum number of high IQ competitive students matter in the student base. I don’t know what this number is – if it is 70% or 50% or 40%? But a certain number it is needed to ensure recruiter interest, and for each student to feel the pressure to compete. And an institution like VIT is able to attract this minimum number. Also don’t forget that colleges such as VIT are selecting from a relative affluent portion of the Indian population, those who can afford to send their kids of English-medium national board schools such as CBSE / ICSE which contribute a significant number of students to these MERIT schools. Parents and relatives of students in these institutions can pull levers to ensure the right internships and interview opportunities, thus ensuring some level-playing field vis-à-vis the IITs.

It is these factors that push a VIT or PESIT or Ashoka in to the MERIT colleges category. And even as these have entered the MERIT category, the decisive advantage that the IITs and top-tier engineering colleges enjoyed vis a vis their less prestigious peers has been declining. It is not surprising that the number of students taking the JEE has steadily dropped from 1.35m in ’14 to 0.93m in ’20; that is a 30% drop.

Over the next few sections of this essay, I will double-click on the characteristics of MERIT colleges, one by one, to better understand them, and what they mean in the context of India today.

The ‘I’ in MERIT

The most interesting of these characteristics is the national or all-India intake. In fact it is interesting to see top MERIT or top-tier colleges in India as one element of a ‘national’ educational and career track that exists in India. The first are the schools. CBSE boards (20m enrolled across K12) and ICSE boards (1.8m enrolled) are less than a tenth of the 250-260m students enrolled in our K12 institutions. But these two national boards account for a large proportion of the feed into top tier colleges – here is a story on how CBSE boards account for the majority of IIT entrants.

Statistics like this – you will see that the percentage going into Liberal Arts colleges such as Ashoka or Krea from national board schools like CBSE / ICSE schools will be even higher – isn’t accidental. There is a strong correlation between access to national platforms and income in India. We have a strong central government that has been getting stronger every year at the cost of the regional / state governments (this trend has been on in the last 70 years). Much of economic and regulatory policy is now determined centrally. It is tough to build a large business in India without expanding nationally (except in a few areas like liquor, real estate and agricultural trading) as the size of the Indian market is small. So if you need to expand nationally, then you need to be able to compete nationally, which means you need to hire people with skillsets that can fit into this environment, which means graduates from these national institutions and so on.

To succeed in India is thus to break free of your regional, vernacular chains, and become part of the urban, national and English world. For, this is where the highest economic rewards are, and also where the highest economic and social degrees of freedom exist. This is unlike the U.S or even Europe (except perhaps France) where you can be a hugely successful regional star with zero national shadow. In these countries, a regional identity or status isn’t markedly inferior to the national one. Not so in India.

What the above has done is to create two parallel tracks of education in India, starting from kindergarten through K12 and college – one national and the other regional. In the national, and elite track, you go to an urban, English medium national or international board school, then to a selective-national-residential college and eventually you join a corporate that has a national or international presence. You interact with your peers in a mix of English and Hindi, and you consume a lot of international and cool local culture (Paatal Lok and Prateek Kuhad). This ‘national track’ India is about 10% of India and gets a large share of the economic spoils, in contrast to the parallel regional / local track that is much larger but has a lower share of the economic spoils.

‘National track’ India

Why does national status or identity matter in India? Well, one factor clearly is that the national identity helps you get into professions that pay better, as we saw earlier. The second is a bit more complicated, and has to do with how a sense of national consciousness (or identity) and elite stature has conflated in India. I am going to have to elaborate this a bit.

A country exists to enable the maximal economic and personal degrees of freedom for its educated elite. If a section of the educated elite cannot operate freely or maximise their wages, then they will chose to transform it (politically or via other quasi-political means) or partition it or migrate to another ‘country’, e.g., fear of getting swamped by the Hindu majority in independent India led to the Punjabi Muslim elite canvassing for and carving out Pakistan. The educated elite is the determining factor because it is they who have the ability to organise and canvass for change. And, it is also equally correct to say that the country’s size is determined by the extent to and ease with which the elite can operate in and maximise their economic wages. The EU’s expansion was a desire by the elite of Western and Central Europe to expand the market and playing field for the elites.

(A quick aside. Globalisation, or really seeing the world as one nation or market, is a clear extension of this. From the 1950s to mid 2010s, we saw a largely one way move towards greater and greater globalisation benefiting the elites, and it seems at the cost of the lower middle class. Brexit, the rise of Trump all seem to be ways by which the subalterns can pull back globalisation and stop their further marginalisation. Now let us get back to ancient India.)

Up until the British conquered India, there were broadly two communities who were somewhat economically mobile. These were the Brahmins and the Banias. Now there is no concept of a national caste in India – all caste identities are broadly regional. But thanks to their relatively greater economic mobility, in these two communities a kind of national consciousness emerged. Prestige and national consciousness, effectively melded together in them. Meanwhile the rest of Indians had a largely regional consciousness, for they saw themselves deriving from their identities largely from their home regions. I remember an evocative portrait of a poor villager Kaccheru in Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, a fictional portrait of 1950s India; all I remember from that portrait is that Kaccheru had not travelled to even the nearest small town near his village. People were largely immobile until recently.

With the arrival of the British came a definitive notion of ‘India’ as a geographic and political unit. From a diverse culture with common Indic elements, we became a nation state. As the Indian state evolved under the British, education, especially English language education, became one of the routes to economic advancement. A tiny Indian interpreter class ‘Indian in blood, but English in taste’ emerged to corner the economic spoils on offer. And with the creation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 and the coming together of the elites to organize against the British further, for the first time, a stronger sense of national consciousness and identity emerged, albeit amongst a tiny elite educated set of Indians. From just Brahmins and Banias we started seeing elite members of other castes and communities (incl Parsis, Sikhs and Muslims) get imbued with a national consciousness and identity. These events solidified the link between national consciousness and elite stature in India. You couldn’t be one without the other.

Since then, and with every passing decade, we are seeing an expansion in the number of Indians with a national consciousness. Today, I would think there are about ~200m Indians who have national economic mobility, about 3/4ths of them being English speakers, the rest are blue-collar economic migrants. These 150m or so Indians are what I refer to as national track Indians / India1 – people like us who fly, use credit cards and drive cars. Every year or so, a few odd million get added to the group.

One way to see India’s economic progress and history over the past thousand or two thousand years is really the expansion in the number of people who have national economic mobility across India, and have thus acquired a national consciousness. This is as opposed to a purely regional consciousness or identity (I am using consciousness and identity somewhat interchangeably). It is as if they have seceded from their regional identity to acquire a uniquely pan-Indian identity.

Enough now about the I in MERIT! Let us take another alphabet – T i.e., toughness of admission, or selectivity of the school.

The ‘T’ in MERIT

Historically selectivity in India was determined by objective merit. That is, a rank on a test (such as the IIT JEE) or even your score or marks in the Class XII exams. This meant studying hard, over 4-6 hours a day outside of your schools hours, often attending a coaching class to prepare for these exams. Most exams are extremely competitive. Success rate in the IIT JEE is <1:100. Other exams aren’t too different. Your performance on the test, or your Class XII board exams determined your entry into the elite colleges be it the IITs or St Stephens or St Xaviers. It really doesn’t matter when you attended debate classes or read widely during your schools years. Your performance came down to those 3-6 hours writing the exam paper and scoring more than most others taking it.

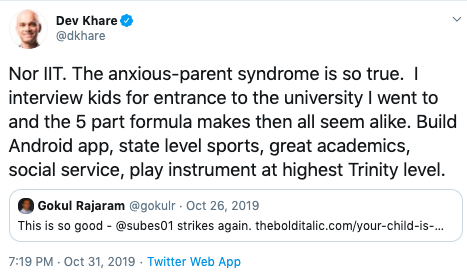

Since the last decade or we are seeing the rise of subjective merit as a way to filter admission into colleges. This is practiced by a small set of colleges – Ashoka, Symbiosis, Srishti etc. Subjective merit involves evaluating admission into a college not on the basis of your performance on a 3-hr test but on a more holistic set of factors – including standardised tests, essays, extra-curricular achievements, interviews and so on. The extra-curricular arms race of course extends to app design and social work as well as this tweet below shows.

What led to the emergence of subjective merit as a parallel evaluation mechanism in Indian universities? A key spur was the growth in new age international schools and the large number of students coming out of these who were smart, but not smart enough or who lacked the competitive hunger to get into colleges that prize objective merit. Recognising this, and seeing in these students a market for their wares, a set of new-age colleges emerged – a large number of them describing themselves as Liberal Arts colleges – to tap this emerging market who can afford to pay well.

A related factor is perhaps the rise of ‘reservations’ or affirmative action where we are beginning to see more representation from the Dalit, Adivasi & Bahujan communities in the government-regulated MERIT colleges the ones where objective merit rules. As the number of seats reserved for the less privileged has risen in these institutions, thereby making it more competitive for upper caste Indian students, we have seen the rise of Liberal Arts / new-age MERIT schools where there isn’t any mandatory reservation for less privileged social classes, and where subjective merit rules as admission criteria. It is useful to see the rise of these newer-age MERIT schools as offering a hypo-competitive pathway that is a safety valve for national track / privileged India.

It is also interesting that a number of these new-age universities have already entered the MERIT colleges category. Unlike some of their counterparts on the objective merit side, such as VIT or SSN which has had to slowly sanskritise its way upward in the college caste stature hierarchy, the Ashokas and Kreas have entered into the MERIT Schools pantheon from birth. The reason is that they are designed specifically to capture those on the national track. Thus they stress selectivity, residential and national intake from the get go.

The fact that we have a sizeable enough, and growing set of institutions in India, that evaluate on subjective merit is vital. Otherwise the only option for the children of the elite would be to go abroad to study, as in China. This emergence of a parallel track points in some ways to the strength of the Indian society and its ability to accommodate and absorb diverse actors. It is also driven perhaps by a desire to increase the number of people with national economic mobility and thus engender greater national consciousness, and a stake in India.

It is worth noting the rise of Hindutva in recent times, as see it as a parallel route to national consciousness. The passion for this ideology has perhaps been greatest in those who do not have a strong enough presence in the national economic layer of India or benefit from it. That is one way to see the rise of jingoism and ethnic chauvinism we have seen of late in India – as an alternative way to give those off the national track a greater national consciousness, and a stake in their nation.

‘E’, ‘M’, ‘R’ in MERIT

I will move over these fast.

English is something that I have written about at length, specifically in the emergence of Indo-Anglians or Indians who speak English at home, replacing their mother tongue. Its importance clearly emerges from a trifecta of factors

- historic signal value – It was the language of our rulers, and if you spoke it well, it signaled that you were part of or supported the ruling elite. That signal still lingers on

- the language of business and technology – English has emerged as the pre-eminent language of business and technology. To speak or write English well is to find it easy to work abroad

- link language in India – It is a neutral language in which to communicate, and means there is no ego around using it to get through.

There is too much path dependency for English’s importance to reduce now despite the best attempts of a lot of politicians.

On to Metro / Residential. It is interesting that amongst the original IITs, the highest ranked IITs are those in Bombay and Delhi, followed by Madras. Those in Kanpur and Kharagpur have been relegated to #4 and 5. I would not be surprised if IIT Hyderabad overtakes these in some years. Ashoka and Krea are located on the outskirts of Delhi and Chennai respectively. Why does presence near a metro matter even for residential colleges?

2 reasons –

- Spouses of Academicians find it hard to get work if you are not near a big city. They hence prefer to live in the city and have the academic commute to the campus.

- It is hard to have a lot of senior corporate interactions if your campus is cut off from a major city. This matters especially for campus interviews during placement season.

These two factors mean that every new liberal arts / new age campus is being set up on the outskirts of a metro.

Privilege blindness

I wrote this as a way to arrive at a better moniker to describe the top tier of educational institutions in India. I was tired of hearing IIT / IIM as a convenient if misleading shorthand; for no one who uses that really means that. When they say IIT / IIM grads wanted, they really mean selective institutions with a certain set of features, which really collapse in to what I call MERIT here. Through my exploration of these features of MERIT institutions, I also wanted to shine a light on privilege, and how it is manifesting itself.

Almost everyone who attends a MERIT institution is in some ways privileged (barring of course those from the less privileged castes who are deserving beneficiaries of affirmative action). These institutions, as I observed earlier, account for admission of 175-200k students annually. Out of ~15m who emerging out of Class XII every year, ~8m enter undergraduate education. MERIT college admissions thus account for ~2% of the total college admission process. So, even if you are from a college like RVCE or TSEC in Mumbai, not seen on par with an IITKGP or an NIT Trichy, it still puts you in the top 2% of Indian students.

A key trait that we elite Indians share is what I refer to as privilege blindness. If you are able to read this in English, then you are one of 2% Indians I call English-fluent. There are just 25-30m who constitute the set of fluent English readers in India – who can read and think in English. People like you and me. And if you earn just ₹1.17 lacs a .month, then you are in the top 1% of India. Yet, we often see ourselves as the middle-class, or at least comfort ourselves that we have middle-class values. We are the upper class but we don’t see ourselves as that.

This privilege blindness in some ways parallels what Prof Satish Deshpande, a sociologist, who writes extensively on caste, refers to as the castelessness of the upper castes. He says that the Indian upper castes, having converted their social or caste capital into economic capital, now have become casteless, while the lower castes have to assert and intensify their caste identity in order to get access to resources earmarked for them. In this context, I can’t but help see the rise of MERIT institutions as beneficiaries of the upper castes’ desire to convert their caste capital into academic capital – ideally one that is recognised or encashable globally. Caste, a regional currency, recognised best within your region or social milieu and safeguarding your occupation, now transforms to the new global currency of merit in India1 or national track India, widening economic degrees of freedom and earning power for the meritorious.

How fast can we expand the number of MERIT graduates, for the number of MERIT school grads almost entirely correlates with the expansion of National track India? And how fast can we expand without debasing the currency of merit? These are the 2 key questions in front of us as we enter the 2020s.

Endnotes

1) How I arrived at the 175-200k number for entry into MERIT colleges: IITs account for about 11k seats, and NITs for about twice that; elite engg colleges will total to about 70-80k seats in all; medical = ~75k, and then the rest spread across prominent Arts, Sciences, Commerce, Law and Liberal Arts Colleges. I could be wrong by 25k or even 50k. Happy to be corrected.

2) How I arrived at 1.5m students graduating from Class XII in the national boards and 3.5m graduating from Class XII from English medium schools: There are ~18m CBSE students enrolled, 1.8m ICSE students and another 200 international school students across K12. I estimate that there are about 1.5m of the 19.8 or so in Class XII. These are all English medium. It is estimated that there are about 45m students enrolled in English. This means there are about 25m or so students enrolled in English medium schools under the state board. I presume that about 2m of these are in Class XII. Adding 1.5m from national boards (entire English-medium) and 2m from state boards gives us 3.5m.

3) I would like to thank Anmol Maini and Karthik Reddy in particular for their detailed feedback on the essay. I would like to thank Anirban Kundu for helping me in coining MERIT as a neologism for elite top tier colleges. Any errors in the essay are wholly mine. Pls let me know if there are any errors either via mail (in the ‘About’ section on my LinkedIn profile page) or my commenting.