In this essay, I reflect on my past five years in venture, my learnings and evolution. My evolution, of course, echoes the evolution of the Indian venture and startup landscape too, and cannot be seen in isolation. So we will take a deeper look at the Indian startup and venture landscape too. In addition, we will try and cover a few questions I (and perhaps other venture capitalists or VCs) get asked frequently – on how we and the industry work, and nuances and trivia around this.

This essay is a long one, and is structured into three parts – the first is a look at the Indian venture landscape over the past five years and my participation in it, viewed chronologically. The second part looks at venture practices, and the craft of venture, and my sensemaking of it. The final section gives you a glimpse of my evolution over these five years, as an unlikely entrant who now seems to have settled down here.

Part A – The Indian Venture Landscape 2018-23

1. Origin Story

Early last month, I completed five years in Blume Ventures, an Indian seed fund. I was, at the time I joined, a very unlikely candidate to be a VC. I was 43, I had never started up before or even worked in a startup[1], had never done venture or even angel investing before. In that context, I was surprised when Karthik Reddy, the cofounder of Blume, reached out to me to discuss if a career in venture, in a firm like Blume, would interest me. Now, it helped that Karthik Reddy (and Ashish Fafadia, two of Blume’s then Partners) knew me from before, for we had worked together briefly at The Times of India Group. It perhaps helped that I used to write and comment on startup business models a bit, and that I had operator experience in media and education, two sectors that Blume was keen to go deeper into. Still, in hindsight, I can’t help but think that it was a tremendous leap of faith for Karthik to reach out to me to explore a career in venture at Blume.

For this piece, I asked Karthik as to what led him to reach out to me. It was indeed some of what I shared above – wanting to add heft to consumer sectors, seeing some of the firm’s thinking reflected in the pieces I was publishing (which he said was “tracking perhaps more than most others were at that point.”) added to the comfort of knowing me from before. An interesting point he mentioned was that he wasn’t entirely sure then if I would have wanted to be an investor or stayed one, whether I “had the courage to pick and live with the risk. We’ve had people who have not been able to live with that risk of writing checks and losing that money, so it’s never easy.”

So what led me to take forward the discussion with Karthik? Certainly one key reason was that I was struggling with my career direction then. I had made a bold move to the education sector, helping the Times Group set up its higher education initiative, Bennett University. But I hadn’t been able to make the move stick, and just around the launch of the University, I shifted out to a staff role working closely with one of the owners. Staff (or individual contributor) roles are hard if you are like me and like being in the thick of the action. They are even harder when you are in your early forties, with all of the anxieties around the trajectory of your careers, and worries around whether you have lived up to your early promise. Blume promised a break from this seeming career impasse. The nature of the job too seemed to fit with my personality, with my craving for intellectual variety, and preference for breadth over depth. It didn’t take me long to respond to Karthik and pursue the discussion. What took long though was the process, with multiple discussions including a few meetings with our Limited Partners (which was the scariest part of the process, for I worried about a disastrous performance from me impacting their perception of the fund!). Finally, around mid-2018, Blume formally made the offer, and I joined a few months later.

Now, these past five years in venture have clearly been the most exciting and rewarding years of my career, in every way possible. Every day brings with it interesting interactions, with young women and men looking to leave a dent on the world. I get to work closely with the incredible founders I / Blume have backed and mentor, and also learn from them. There is immense variety in your working day. In one day your discussions can range from a morning coffee with founders of a skilling startup, to afternoon lunch with someone building a marketing copilot, to a late evening encounter with a healthcare founder. I like to think of these pitches, each with a distinct vision of the future, as ‘postcards from the future’. They can’t all be right, and not all will succeed, but the ability to influence some of these and help support in creating the future is a great reward.

It has also been an exciting period in India’s history with our emergence as a digital welfare state, built on easy access to the mobile phone and cheaper bandwidth, along with the Digital Public Infrastructure (such as UPI, ONDC) that has been created over the past decade. We are also increasingly seen as an ascendant power, helped no doubt by geopolitical shifts and trends such as China + 1. Global investors, especially in the U.S., see India as the next China, and are increasing their exposure to India in their books. In coming years, we will see more capital coming, and that means that the venture and startup ecosystem will only expand further. I am grateful that I get to be part of all this excitement and tumult, and indeed be paid for it.

2. Path dependence

Path dependence refers to how initial conditions or events constrain and influence the outcome or evolution of later conditions. Our careers, our lives are all subject to path dependence, and my venture career is no different here. When I look back at the five years, I am especially thankful to the early hit I had in Classplus, which was effectively my first pick (in early 2019, in my first year). Even before our legal docs could close, Classplus was accepted into the Sequoia Surge program, and then within a few months, on the back of the rapid growth of the existing SaaS and the new marketplace business, they had a large Series A at a big bump up. Their early breakout and success gave me a lot of confidence, and helped give me assurance that I could have a venture career.

Now, all of this still doesn’t mean anything yet. There is still a long way to go to realise a return or exit on Classplus. That said, the early hit in Classplus helped a lot. Feedback cycles in venture are very, very long. You can sometimes go years into an investment before you realise if it is working or not. Hence, to see rapid revenue growth, and investor love, in a company you picked in your first year was life changing. It told me that I could do well in venture, and validated Karthik’s somewhat risky decision:)

For someone looking to build a career in venture, an early hit can make a lot of difference. It makes it easier for the firm’s leaders to trust you and assign more investment dollars your way. It pulls in higher quality inbounds earlier in your career. It makes outbounds easier. You have a lot more confidence to push your view in internal discussions, and so on. In the absence of an early hit and perhaps a longer time for your picks to break out, you need to have a lot more internal confidence and mental energies needed to keep yourself motivated.

It was interesting to see the above thought reflected in a statement made by Mike Maples, Jr., who founded and runs Floodgate Ventures, a highly regarded seed firm (portfolio include Lyft, Okta, Twitter etc.). He said, in a podcast: “One of the secrets to VC is to get lucky in the first five years… I have seen very few examples of someone who is long-term successful who didn’t have a big win in their first five years.” A key component of luck for me, apart from the Classplus pick, was the timing of my entry into venture.

I joined in ‘18, when asset prices were still realistic. The seed round for first time founders was $750k-1m. Then came COVID. The panic of March-April ‘20 transitioned into the buzzy bull market in asset prices – public and private. The seed round for first time founders was $2-2.5m now. Investments that typically took months to close pre-COVID now took weeks, sometimes days.

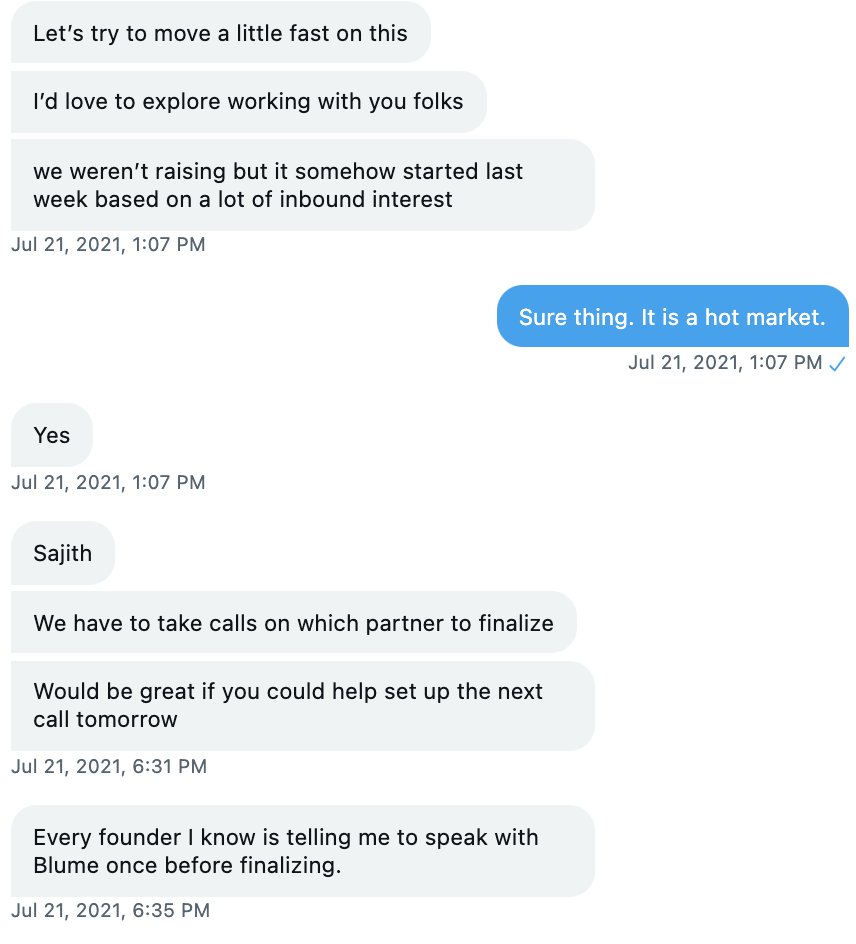

Here is a screenshot of a twitter DM chat with a founder from those days (mid-’21).

In the buzzy boom times of ‘20 and ‘21, all of my sub-portfolio, mostly invested pre-COVID, saw uprounds. A few, like Classplus and Leverage Edu, had multiple uprounds. Some of these uprounds were done by growth / multistage investors at tremendous deal pace, like they were worried that their funds would devalued overnight. A portfolio co of mine went into a meeting with a well-known growth / multi-stage investor and after a 45-min meeting on a saturday evening, came back with a $6m termsheet (they got an mail the next day). It wasn’t just financial investors. Strategics were active too. I had two quick cash exits – one for 2x in less than six months after our investment, and the other at 4x in under a year of our investment. It was a surreal period when it felt like I could do no wrong. That said, to be honest, it wasn’t that my performance was extraordinary relative to my peers. The amount of money sloshing around lifted up all valuations. But all of this madness wasn’t to last.

The raucous party of 2020 and ’21 eventually gave way to the hangover, and then to the painful morning after of 2022 and ’23. Venture gravity shifted. What would have easily commanded an upround a year before saw longer times to close (if at all), with compressed valuation multiples. The growth market just froze, and is still yet to thaw. Thus, if one started investing in 2021 and ’22, even if they picked the right companies, they would struggle to get uprounds. In this bear market, uprounds, traditionally indicators of success have dropped sharply. Feedback cycles have stretched. Thus as compared to someone who started investing in ‘18 or ‘19, the investor who began in ‘21 would need stronger internal motivators to keep going, given the fewer uprounds and thereby proxies for success. In that regard, I got lucky with the timing.

3. The hangover and the headaches

In 2021, at the peak of the party, we saw venture investments (by funds in startups) in India more than triple to $38b or so. India became the third largest venture market, overtaking the UK. In 2022, venture investments dropped by a third, as the wheels came off the venture jalopy. When 2023 ends, it is likely that we will see the 2022 numbers halve. The funding bubble and the rapid deflation leave behind a few scars, or headaches.

One, there are a large number of companies including unicorns that raised their last rounds at high valuations. Some of them, who benefitted from COVID tailwinds, have seen a drop in revenues since the online wave receded. They are in a tough spot. Multiple compression is already a given, and now with lower revenues as well, it is highly likely that the next round will be at a massive discount to the previous round. Some of them do have sufficient monies till they can do an IPO. It is the ones who have burnt through the monies, or do not have an sufficient enough runway who are going to be in trouble. Not all will return funds and shut down, though some have done so (FrontRow for instance). Some will linger on, becoming zombiecorns (like Quikr).

Two, we have seen misreporting of numbers as founders tried to keep the story going even as their revenue dipped. There have been a bunch of these incidents, though the one that disturbed me the most was Mojocare, primarily because one of the cofounders was an ex-VC, and he was also backed by his previous firm. Something about the fact that he would have been highly trusted by his ex-colleagues and some of them may even have blindly backed him, and yet he chose to indulge in fraud, was disturbing. Now, for those of you who ask but how come VCs didn’t know that as they are on the board etc., and don’t you double click on the numbers etc., the surprising truth is that in the venture context, a founder who really wishes to misrepresent numbers can get away with it if they so wish.

The venture business is built on trust. VCs bet on and back founders after a few hours of meetings; in fact the total time that VCs spend with founders before we commit to an investment can be less than 10 hours at the early stage, sometimes even lesser. Of course this is spread over a few weeks. Then as a VC you are juggling multiple portfolio companies. Most of your interaction is with the CEO founder (occasionally with other founders, and rarely with their L1s). In this context, it is very difficult for the VC to do deeper checks without upsetting his or her relationship with the founder. It is a bit like the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle applied to human relationships – the act of verifying the numbers shared by the founder creates mistrust in the relationship. Because you are typically one of many VCs aboard the company, you will never want to appear excessively questioning because you feel the founder will then start favouring other investors.

Why does the last matter? As founders rise in profile, thanks to funding and growth, the power equation shifts in favour of the founder. Other younger founders reach out to them, sometimes for mentoring, sometimes for angel investments, and thus the rising founder becomes a key source of deal referrals or point for reference checks. There is now a distinct asymmetry in the power equation in favour of the founder (unless it is a very elite VC, say someone like the founder or CEO of the fund). There is now limited incentive for the VC to upset the high-profile founder with questions around numbers.

This isn’t unique to India. This is in fact a universal issue. Here is ex-Benchmark Partner, Bill Gurley talking about it: “There’s a systematic problem in Silicon Valley, the venture capitalist board members are finding it harder and harder to speak up and hold entrepreneurs responsible for financial performance. Our business has gotten super competitive. What the venture capitalist is afraid of is losing the next big one. If they get a reputation — years ago [some of the best venture capitalists] were known for storming into board rooms [to demand fiduciary responsibility] — if you get a reputation like that you won’t win the next deal.”

I don’t think there is an easy answer to this. VCs have to be bold enough to be willing to risk upsetting the founder, given the fiduciary duty they have even if it comes at the cost of cutting off deal flow. Founders need to understand that if the VC is asking uncomfortable questions, it is in their (founders’) best interest to address the same without getting discomfited by the line of questioning.

In an ideal world, where founders are raising every 18-24 months, the incoming investor does a DD (Due Diligence) to verify the numbers and then wires the money. Typically in such scenarios, any fraud gets sniffed out. Typically a company that is raising frequently is usually doing well. Much of the scandals tend to happen either when there is a long time window between rounds, or when revenue dips before a funding round and founders (a tiny minority of the founder set) want to manage the numbers.

Over the past few months, in response to these scandals, we are seeing a gradual tightening of the process around reporting and audit. There is a lot more awareness and consciousness of the process on both ends, and a willingness to adopt stricter measures of reporting. Hopefully this will continue.

One other emerging area of VC-founder strains in recent times is the topic of founder growth and evolution. Let us unpack this.

4. Founder evolution

The CEO of a consumer products company, who is familiar with the startup ecosystem (he angel invests and mentors unicorn founders) told me that he saw Indian startup founders hit a ceiling in their development and growth fast. He said he saw Indian startup founders as paratroopers who can quickly grab 5-10% territory share (read as market share) using shock tactics / disruptive product, and then use VC money to go a bit deeper as cavalry to grab say 20-25% territory / market share. But to grab 40-60% he said you need to be infantry, or even occupants, and be willing to invest for the long haul. Here, he said, he saw Indian startup founders struggle to go beyond cavalry to infantry, barring a tiny minority.

If you look beyond the rather macho military analogy, what he is saying is that most Indian founders are good for the 0 to 1, or at best 1 to 3 stage of company-building, but struggle in the 4 to 10 stage (where 10 = IPO), where they need to hire the CXO set or their L1s, delegate to them, bring in processes, systematise operations, tone down all the drama and bring a certain amount of grownupness to the company. To me this wasn’t entirely surprising when I heard this.

As prep for this piece, I asked a few X / twitter followers for questions they would like me to answer in this piece. Akshat Jain (@akjain7353 on X / twitter) asked me for a belief / unpopular opinion of mine that could get me into trouble or a situation like the picture below! Well, here goes.

Coming from my two decades in corporate India, where I had worked and interacted with experienced, seasoned operators, I was surprised with the uneven founder quality, even in soonicorn and unicorn startups. This was especially true of consumer startups, who are founded by twenty-somethings (B2B startups see more experienced founders, typically in their 30s or even 40s sometimes). As these startups grow and scale, you do see many of these young founders scale and grow themselves. But there are also many founders who struggle to scale as well.

Despite the fact that weak leadership is impacting long-term value creation (as much for the founder as for the VC), this doesn’t lead the VC usually to make any leadership change. For one it is a lot of work for the VC, to persuade the founder to reconsider the leadership role, and step aside, and bring in a CEO to take over (it is done in exceptional circumstances). If you know us VCs, given we are juggling so many balls, it is hard to get involved so deeply in an investment and effect management change. It typically happens if there is a large position at risk (such as for Bill Gurley and Benchmark re Uber, or Sequoia and Bharat Pe, two scenarios where leadership change was effected) given founder misbehaviour. Apart from lack of time / energy, you are also reluctant because of the risk of being seen as founder-unfriendly.

I read a fair bit of venture history as a venture nerd. A favourite hobby is collecting and reading books on early venture history, from the ‘80s and ‘90s (clearly you know why I don’t get invited to many parties!) From those, I learnt that this default of founders staying put as CEOs (or even becoming CEOs) was actually not the default, when the U.S. venture industry began to take shape in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Instead it was very common for VCs to effect change in leadership. From The New Venturers by John W Wilson (1985): “Neil Bond of New Enterprise Associates (NEA) estimates that a major change of management is required in 80% of the deals that NEA originates. The skill with which a venture firm uses its boardroom power can be the most important factor affecting its return on investment. Some try to keep on tap a cadre of venture managers who can be moved into trouble spots as the need arises.”

Of course, much has changed since then. The average founder quality and skill sets today are far higher. A lot of company-building and scaling concepts are now available for free online for founders to learn from. Social media makes it easy for founders to connect with each other and for senior founders to invest in and mentor younger founders, helping them learn faster. VCs are also far more reputation-conscious these days. So I don’t really anticipate a return to the old defaults, either in the U.S., or even in India.

That said, I would love more candid conversations, as much led by founders, on how they see their role in their startups going forward. For every Sriharsha Majety or Abhiraj Bahl evolving at a rapid pace, there are many founders (including some who helm unicorns and soonicorns) who aren’t evolving or growing at the pace needed by their company and thus constrain the growth of their company. It is as much in their best interests (as large shareholders) to bring the best management for their companies, and take a back seat (or step down) and safeguard their equity and see it generate the highest outcome[2]. Not everyone can and needs to evolve from the 0 to 1 to a 10 stage (IPO). You could make as much money doing repeated 0 to 1 to 1 to 5 journeys, and then bringing in senior operators to take over.

With that, it is time to move to Part B, to take a closer look at the practice of venture.

Part B – Venture Perspectives

5. A two-tier venture market

Recently, someone who got to know about my milestone of five years in venture asked me “In your 5 years, what is that one thing about venture that you have seen most people get wrong / do not understand correctly?” My answer to this is that it is actually two things, interconnected. The first is that, the venture or startup market is best understood as a two-tier market, not a single venture market. There is a market for first-time or fresh founders, and a market for repeat or fluent founders. The investment criteria, the investment amount or deal size, the valuation (which is a function of the deal size and dilution) are different for the two tiers. They are as good as two different markets, or worlds.

A first-time founder who isn’t a senior operator, or doesn’t have 2+ years of experience in a reputed unicorn startup brand, will struggle to raise a pre-seed round from an institutional investor / VC (who invests other people’s money). In the seed round he or she will need to demonstrate traction. In today’s environment, with about $250-500k annualised revenue (or ARR) and visible traction, they may be able to raise a $2m round on $10m post. A repeat founder, or experienced operator, depending on their profile can today raise even a pre-revenue formation round of $3 to $10m (even higher in some cases) at 20-25% dilution. Why is this so?

When you are a second-time founder, the demand-supply equation inverts in your favour. Because of the perceived lower risk of failure of the experienced second-time founder (though I haven’t seen a study that decisively concludes that second-time founders deliver more returns than first time founders), and because there aren’t that many experienced second-time founders, you have more VCs chasing fewer high quality founders. When that happens, founders have the power and they can pick the VC they want to work with. That reflects in the higher prices and deal sizes where experienced founders are concerned. Here, the VC business inverts to a sell-side business – we need to sell to founders. As my colleague Karthik Reddy mentioned in a podcast — “the trick of the trade is actually, it is not about you saying I know how to pick well, it is whether the best entrepreneurs want to pick you.”

The traditional view has been that VCs hold all the power or at least are more powerful than founders, because they control capital allocation. Yes, this holds at the early stages of company-building, especially when the founders are first-time founders, and when the company desperately needs capital (any stage, and could be first-time or repeat founders). Outside of this, the power equations can wary, and often even invert in favour of the founder when he or she is a repeat founder, and the VC is early in their career. Then there is also the situation I alluded to, in Section 3, where as a startup grows from early to late-stage, the founder profile and power increases.

A good way to think of the first-time founder market is as a buy-side market, with the VC in a position to dictate terms and holding disproportionate power here. The repeat founder market, where the founder has far more power – more VCs chasing him than the reverse resulting in his or her being able to command higher deal sizes and valuations – is effectively a sell-side market as the VCs need to sell themselves to the founder. Alex Bangash, who runs Transpose, a fund of funds platform, describes this upper tier of venture as an ‘access class’, and describes this as the only investment class where the asset picks the manager.

The implication of the above is that to compete in the more important upper tier venture market – where the more fluent or semi-fluent founders are – you are competing in a market where the founder effectively picks the investor, or at least has far more choice, and hence the VC has to sell to the founder. This brings me to the second and inter-related point (of what people get wrong or misunderstand about venture).

6. Understanding venture as enterprise sales

A good framework to understand venture, at least the venture world of repeat or fluent founders, is to see it as a market where the VC is a purveyor of their brand of capital. In the case of Blume, all of us in the investment team are purveyors of the Blume brand of capital which consists of $2-3m (our typical investment corpus), investment team’s (Partner or Investment Lead’s) time, and platform services (recruiting, fundraising support etc). Effectively we are selling this bundle. Blume’s brand of capital is distinct from Nexus’s brand of capital, or Stellaris’s brand of capital, even if the amount invested is the same, given it comes with the Partner’s time, the brand signal, the platform services corralled by the Partner + investment team, etc. Founders decide which brand of capital they think will help them grow their enterprise the most, and pay for it with equity of their company.

Now, VCs do need to be cautious in determining which company’s equity they should get access to, for they have 25-35 different companies (typical size of fund portfolio) whose equity they can get, and they need to make sure that these will grow in value as far as possible, and will not all be duds. Given the power law inherent to the venture business, about 3-5 will need to work out outstandingly well. The general assumption is that the more experienced the founder, the higher the chances of success, and the more that equity will grow in value.

Thus fundamentally the VC economic model is that they are selling their brand of capital, for which the currency is the startup’s equity, and the ICP (ideal customer persona) is a repeat or a rising founder. The job of the VC becomes akin to the AE or Account Executive at an enterprise SaaS co, responsible for identifying, contacting, engaging and finally persuading the elite founder to accept their brand of capital. Venture is from this perspective, enterprise sales of a kind.

Viewing venture from this lens, gives you a sense of how venture firms recruit. We need to recruit candidates who we think will be able to connect, engage and persuade repeat / rising founders. This is signalled through past experience as founder or as VC, or a senior operator who others founders will identify with, or proxies such as access to relevant networks (academic or corporate), content creation in this space (blogs, newsletters), past or present experience in community management (Saasboomi, Headstart, Product Folks etc.), or any activity indicating exposure to startup activity (say, angel investing) thereby giving us confidence that the candidate can connect and engage with a star founder and leave a good impression.

If you applied to a venture firm, and got a rejection, but didn’t get clear feedback, then it is likely that some other candidate signalled the ability to connect and engage with a star founder better than you. Sometimes even ticking off most of these boxes by a candidate is not enough – there may be others who tick more boxes or tick better. Also, given that most venture teams are small, and there is always a larger number of candidates than roles available, it is not surprising that venture is one of the harder segments to break into.

7. “A customer service job with a lot of email”

One of my favourite movies, and one I think that perfectly distils the venture capitalist’s pursuit of their craft, is the movie Jiro Dreams of Sushi. It is a documentary that profiles Jiro Ono, who ran a top-tier sushi restaurant in Japan, with his unending quest for perfection. Chef Jiro does the same thing day after day, buying the best fish possible, preparing the best sushi he can and serving it to diners (He is no longer active in the kitchen, as he is 98!). The movie celebrates his craft, and importantly his attitude of everyday improvement and striving towards perfection.

The above quote in full is “I do the same thing over and over, improving bit by bit. There is always yearning to achieve more. I’ll continue to climb, trying to reach the top…but no one knows where the top is.”

To succeed in venture, I have always felt you need to bring this mindset, that some call that of a shokunin, a japanese word for an artisan devoted to his or her craft and spending a lifetime in pursuit of achieving perfection. Just as for a sushi-chef, so too for a VC, a lot of the day to day tasks don’t change as you shift from being a junior VC to a senior one. You continue to source and meet founders, answer inbound mails, support founders, help with exits and so on. Yes, the degree of emphasis changes. As a senior VC, you focus a lot more on certain aspects of the process where you have a distinct advantage – say winning a deal, or supporting a founder on a thorny issue, or exits, and so on. In addition the senior VCs time goes a bit more into fundraising (sometimes a lot more) and org management. But I would say even with all of this at least two-thirds of the day doesn’t change structurally. You are in calls or meetings (or mails) evaluating potential founders, and helping your existing founders.

The calls and pings can often be overwhelming – everyone it seems wants to talk to a VC, be it potential founders who want to bounce off their latest ideas, or your existing portfolio founder needing an intro, to a journalist who wants your perspective, and so on and so. This leads to what Mamoon Hamid of Kleiner shared in a podcast that Leo Polovets captured succinctly – “every meeting is energizing, but the aggregate of all meetings is draining”.

I will touch upon another challenge in venture, also described above. It is one that is most apparent to operators / founders moving into venture, and that is the nature of feedback loops. It can often take a long while to see the impact of your investment. Typically growth in performance and progress in the company, is reflected in an upround, where a new investor comes in to lead a round at a higher valuation, typically 18-24 months from the previous round (though in the go go days of ’20-21 we saw uprounds in months, often with no improvement in performance.)

For those used to seeing feedback in hours or days, this long a feedback loop can be disorienting. That said, you can track performance and growth of the company in revenue and engagement metrics (DAUs, retention rates etc.) and use that as a proxy. Efficiency metrics (burn multiples, magic number, rule of 40, CM2 +ve) too can be used along with the revenue and engagement metrics to judge progress, not to mention qualitative metrics. But eventually you do need to see all of this progress reflected in an upround, if at all for the reason that the company will need funds for further growth at some point.

We now head into the final part of the essay, looking at my personal evolution in venture, and detailing my personal approach to winning in venture.

Part C – Getting Personal

8. Transitioning from buy-side to sell-side venture

A natural progression for me over the past five years has been transitioning from largely ‘buy-side venture’ working with first-time or fresh founders, into part ‘buy-side’ and part ‘sell-side venture’, where I am beginning to work with more experienced operators or second-time founders. To move up this tier and to participate in sell-side venture, it helps that Blume’s fund size has increased (our Fund IV was $290m in corpus, up from $102m in Fund III). Entry into startups founded by second-time or experienced operators turned founders don’t come cheap, and thus the increased fund size gives us / me the ability to play in the round. The time spent in the industry has helped as well, as my network expands, and of course all of the content that I generate helps a bit as well, in expanding my reach, and brand.

I like to think of all of the activities associated with discovering and partnering with these experienced (or rising) founders as Finding (i.e., the next big startup). Finding includes everything pipeline-related from creating it (via content, thesis writing etc.) to the decision as well as the investment transaction. Minding is what comes after it which includes all things that the VC does, post the transaction, to help the founder succeed. These are the two broad areas of the VC’s role[3]. There are other ways to structure the VC’s role as well. I have heard of a source, select and support framework as well.

Back to Finding.

The three broad sub-buckets in Finding are access, picking and entry. Access is visibility of transactions and getting to know that so and so founder is starting up, or is raising. Picking is deciding yes or no to the investment. Entry is getting to participate after you say yes (in a hot deal, the founder has choice to select the investor s/he likes). The younger the investment team member, the more they should focus on access. They can support on picking by helping with the research and investment docs etc. But broadly the final call on picking, as well as enabling entry / winning is the senior VC’s domain.

There are different ways to increase your access. The winning strategy is to put yourself in a slot where the best referrals (from founders or angels) come to you. You do this by creating a reputation for backing the best companies, or being most helpful and / or being the purveyor of a reputed brand of capital. Of course, to get here is a long journey usually, and in the interim you still need to attempt to generate great deal flow / work on access.

There are of course many ways to generate deal flow / pipeline. Your strategy should take into account your strengths and your right to win. For me, one fundamental constraint I have is that I am based in Noida, the second hub of the second startup hub in India:) I can’t do ‘ground cover’ (meeting angels, or microVCs and building relations) as well as my colleagues in Bangalore can (though I do travel at least once a month into Bangalore). Hence I focus a bit more on ‘air cover’, which is largely content (an area where I have strength), and try and build a brand to generate inbounds. Of course one challenge with inbounds is that it is predominantly first time founders.

On picking, my philosophy has evolved over time to outweigh Traction or growth over Team or TAM (market) specifically Traction > Team > TAM. Now, I couldn’t have done this as a pre-seed or early seed investor as traction bets are more expensive (given they are a bit more later stage or closer to PMF) and I couldn’t have afforded such high traction companies. Hence as a pre-seed or early seed investor I would have outweighed Team over anything else. But thanks to our larger fund, our sweet spot now is $2-3m at Blume and hence we have the ability to pay up for some traction, and thereby the reduced risk that comes with performance.

Why do I not focus on TAM or market size? While I do believe it is important to have a large market to tap into, I do believe that for category-creating products, a large TAM is not apparent early enough. It becomes visible only later, Sometimes it needs to be created. As Jason Calcanis said in the Farnam Street podcast, “The best products induce a market to manifest itself. The market for a meditation app and the TAM / total addressable market of meditation when I invested in Calm, 5-6 years ago when nobody else would invest in this company or very few people, the TAM of meditation apps was zero.”

As an investor my biggest mistake came when outweighing TAM (I passed on WhiteHat Jr in late ’18, and it exited in Aug’20 for $300m cash) over everything else. Karan Bajaj, the founder of WhiteHat Jr, who I passed on, found my candour and consistency refreshing – we had two calls, and in both I mentioned how I felt the market he was after (What I call India 1A) was niche, and hence we would have to pass given the small TAM. He remembered the interaction and put me on his list of favourite VCs in an article he wrote subsequently!

Another big miss was Captain Fresh, the seafood marketplace – this one was not so much TAM as much as the ownership requirement. I wasn’t sure I would get our desired 17-18% (we had a high bar then!) and decided not to take forward the conversation with the interested founder. The company grew rapidly, with rapid uprounds (though of late it has had its challenges). Since the miss, I have become a lot more flexible on stake size, and being open to get in even if we are only able to get 12-13% stake, and be open to building up more through secondaries and super pro ratas to 15% (anything more isn’t easy, especially for repeat or fluent founders).

I was listening to a podcast featuring Roger Ehrenburg of IA Ventures, the seed fund that has generated incredible returns. In that he mentions that they like to invest such that they get 15-20% stake in the co, but sometimes the deal may get expensive. In such a case he said they are open to compromising on ownership but not capital discipline. They invest the same amount they usually do, but get a lower stake, and then build it up at the Series A and B stages. In great companies with say 100x-200x, how does it matter if you overpay a bit? I concur with his thinking.

Misses like WhiteHat Jr and Captain Fresh hurt, both financially, and emotionally. As these startups started doing well, and I saw the news of their uprounds, I felt an immense regret for passing up, often played back the decision in my mind, thinking about the circumstance around my (now) costly decision. That said, such antiportfolio (which is when you formally pass on a company and it goes on to be a success) is a feature not a bug. As a VC you will rack up many costly misses. Of late, I have also begun to worry about what I call my jealousy list. Startups I would love to have invested in, but which never pitched to me. These hurt too, in a different way. Here I think: did they not even find me worth reaching out to?

Over time, you learn from your mistakes, and successes and you build your pattern library. Thus, you develop your investment style which is really this library of patterns or thumb rules, with an instinct for when to make exceptions. These are thumb rules or guidelines and not definitive or absolute rules. A big learning that I have come to, and one deeply influenced by my interaction with my Blume investment partners (Karthik, Sanjay, Ashish, and Arpit) is that there are many paths to success in venture (in both Finding and Minding). There is no one definitive approach it seems. For every rule I have proposed in our internal discussions, my partners have found success stories that violate those rules. In fact at Blume, we try not to have too many hard or absolute rules.

For instance, one thumb rule I have is to overweight teams / founders who have known each other for years. This of course means that I will struggle to prioritise teams from Entrepreneur First for instance (who are matched together in the program), but if they have high traction, or are building in a space I have a lot of interest in, then I could take the discussion ahead. Similarly I have thumbrules against working with startups over four years old (the older the startup the greater the tendency to go for a beach money exit) or those represented by an investment banker (as I see it as an orange flag that the founder is not fluent enough to source meetings with investors or find a link into me). But none of these are absolute. Both my recent investments violated these rules. Virohan was over four years old, and Freakins was represented by a banker. Have high bars or hurdles, and be open to revisiting it for an exceptional company, is perhaps the only absolute rule I have!

There are two quotes that I recently read, which I think are relevant here. First, from Nikhil Basu Trivedi: “Exceptional companies deserve exceptions. And it’s a mantra that I’ve tried to always have in my venture career, which is, yes, you have this model of how you want to invest, this dream idea of portfolio construction and the profile of the company that you’re looking for. But it’s so often the ones that you consider an exception for, the ones that just blow you away that feel like outliers, that end up being the ones. And so I’ve always tried to have that in the back of my head, which is at the end of the day, all of what we’re doing in our job is searching for the outliers and the truly exceptional companies.”

The second is from Karthik Reddy (again!): “Our business is a business of matching patterns, but people mistake patterns for formulae. But the only stories worth telling are those built by exceptions.” How true!

9. Minding

From Finding to Minding, which is managing the company post investment, and helping the founder and team succeed.

Are there ways in which the investor can best help the founder? Well, there are different portfolio support styles, just as there are different investment styles. Over time I have evolved to the philosophy that the best founders often need the least help, and that you should actively focus on picking the founder who needs your help the least. Well, I should clarify this. Typically, with second time or fluent founders, you don’t need to invest as much time into helping them get to product-market fit or in scaling. Given the experience and network they have, they will figure it out (or not). The relationship becomes more pull-based, where they will reach out if they want any help.

However, such a strategy (of picking founders who don’t need help) can work best when you have the ability to work almost exclusively with experienced founders. So, this strategy can work perhaps better for me now, but clearly it would have been harder to make work, say when I was just starting out, or if I were with a less known fund, when I would have had to work with first-time or less experienced founders.

That said, even the most experienced founders do need some help. As a VC, asking the right questions, and broadly ensuring that they are not going awry or heading in the wrong direction helps. Being available as a sparring partner to the founders, and creating a safe space for them to vent, helps. Giving them feedback on their metrics, and giving them a sense of how it compares to their peers, helps as well (an outside-in perspective is hugely useful). For B2B companies, introductions to potential customers always helps. Then there is helping them recruit the right talent, be it full time or even advisory. And then of course there is connecting them with investors and advising on fundraising – this wraps the list.

Each investor typically has a favourite area of sparring or focus with the founder. Typically the earlier you invest, the more needle-moving product inputs are. But when you come in at the stage I do, the MVP (Minimum Viable Product) is done, and now you need to start taking it to market for early feedback and validation. GTM (Go To Market) becomes critical at this stage. And that is where I have tried to be most helpful to my founders – helping them figure out if the GTM motion is working and how they could iterate better here.

One area in which my background and the long stint in the corporate world helps is perhaps in bringing a strategic lens to the business. I do think younger operators bring strong tactical skills, in product or GTM areas. This is enormously useful of course, but at the same time, being able to see the business from a strategic lens in terms of the right to win, aligning that with the business model, the GTM / customer acquisition playbook, picking the right metrics and aligning all of this against the incentives / reward systems, is also very helpful to the founder. Most of the founders I work with have an intuitive grasp of this, but articulating and setting this out to them in a structured manner is hugely helpful.

I shared above that as you start working with more experienced founders, the relationship becomes more pull-based where they reach out when they need help (apart from the scheduled formal catchups like board meetings or monthly reviews). This means you are essentially on founder time, and given that founders are always on, you are effectively always on too. As you seek to build your brand, it becomes hard to have any firm boundaries between work and non-work. Now, this is broadly true of all high-end service industries like banking, consulting, law etc., but in venture your customers are younger, closer to you and keep stranger hours. Like in all professions, you mimic your customer’s hours.

A mitigating factor is that many of these pings (calls, whatsapp messages) are brief, or demand brief interventions. But they are continuous. At 10pm, there are always a dozen unread whatsapp messages which need to be responded to. Correction. At any point there are always a dozen unread whatsapp messages that need to be responded to. And you are always responding (at least I am), in meetings, during dinner with the family, while reading etc. Sometimes I fear that I have lost my capacity for deep concentration as a result of all of this continuous whatsapp use. Recently I heard about a VC at a leading fund who doesn’t have whatsapp installed on his phone. Life goals!

10. Navigating work and life outside work

Given these pressures on time, most VCs become maniacal about productivity hacks[4], always trying to wring an extra minute from their schedules. I am no different. As I steadily got busy and the number of inbounds increased, I tried a lot of tools and approaches to handle the work load. It is always a struggle, but I like to think that I have been able to get better on this front.

What worked for me was a combination of hacks.

One, I had to find some way of managing an endless series of requests for meetings, some seeking mentorship, some for picking my brain. This was hard, as many requests seem genuine, and you are worried that saying no will look rude. But if I agreed to even half the requests then that is half a day of meetings. So what I do in these contexts is that I don’t say no right away (except in cases where I cannot help). Instead, I reply with a templatised mail saying I can’t meet now, but encouraging them to share their thoughts via email. I have found that in these contexts, nearly two-thirds do not reply. Of the rest, most are satisfied with replies or can be managed via emails. Eventually only about one in ten requests who write in asking to pick my brain or need mentorship need to be met.

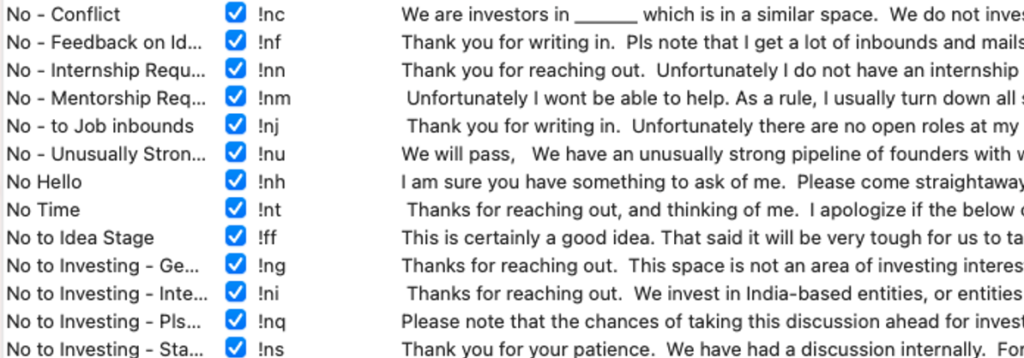

Two, similar to the templatised mail I use above to reply to those seeking mentorship time, I have another 50+ snippets / templates in Alfred (you can also use Raycast) that with a couple of key strokes, I use to reply to mails, or whatsapp messages. This helps in blitzing through emails. See below a screenshot of some of the snippets i use in Alfred.

Another hack that worked for me was making 30min meetings as the default, and trying to persuade those requesting an inperson meeting with me to do a zoom meeting instead, even if in the same city. It is much easier to propose 30-min online meetings than 30-min in person meetings. I suppose one advantage I have is that I am based in Noida, a bit away from the main hubs. So it is easier to use distance as a reason to suggest online catchups. Being based in Noida has another advantage. There are very few startup events (in fact none) unlike in Bangalore, or Gurgaon, with their zillion startup events.

Despite all of these productivity hacks and tactics, eventually you do run into the laws of physics. There are only 24 hours a day, and you have to allocate it across work, self, home and sleep. Something has to suffer and it is usually not work:( The all-consuming nature of VC means work invades all other zones. In particular I have found maintaining fitness a struggle. You can carve out time, but you struggle for energy, and consistency (like say maintaining your diet or workout regimen). Travel, varying schedules, the late night texting (and occasional international zoom calls) all make it tough to stick to a consistent health practice / regimen. I may have added about 10 kilos since I moved to venture, and despite efforts, it has been hard to make the reverse journey of shedding weight work. I have found that while exercise hours are still manageable, it is maintaining a consistent diet that is tough, with all of the travel, and the odd hours and the frequent events. Not to mention my weakness for food!

11. Learnings and Unlearnings

Over the past five years, there have been a few strategies I have leveraged consciously to drive faster learning.

Early on, in my interactions with founders I felt the lack of a startup background given that I had never worked in a startup or been a VC before. I tried to remedy that with a crash course in reading and observing / absorbing startup lore. Startup and VC podcasts to me seem a disproportionate source of startup and venture wisdom, given that they get founders / VCs who don’t have the time to write to share their wisdom. I relied on these hugely to learn. I still do. I try and catch up at least three startup / VC podcasts a week, without fail.

Historically, VC and themes around it – portfolio construction philosophy, fundraising and LP management, fund operations – were knowledge you gleaned only from 1:1 interactions with the GPs (General Partners) of these funds. Typically that meant only the Indian GP who interacted with his or her counterpart in the West absorbed the learning. It wasn’t easy for someone junior to get access to this lore. But today thanks to podcasts such as 20VC, Venture Unlocked, Invest Like The Best etc., anyone sitting in India (or anywhere) can learn about all of these aspects. The democratization of venture arcana has been an incredible development for any aspiring VC.

Another area I was mindful of was to never look down on youth. I entered venture when I was 43. A lot of the founders I interacted with were in their 20s. A lot of my colleagues were in their 20s too. Coming from an old school corporate, with its traditional style of decision-making, I was mindful that I had to unlearn some of what I had picked up over the years. I decided that at Blume, I wouldn’t ever leverage my seniority or age to push my view through. In fact, I went the extra mile in encouraging younger colleagues to voice their view, as well as encourage and appreciate contradictory views, to get people to open up and be candid.

Another factor, helping me learn faster as well as help get better (and more) insights, has been my writing. Now, writing has been integral to my identity as an investor. As one of the few Indian VCs who writes, it has helped me stand out, and carve out a distinct hyphenated identity as a writer-investor. I have heard myself being described sometimes as a content-first VC. It is a tad inelegant, but is a good description of my my identity. Beyond this identity, and even the fact that it helps in generating inbound, there is also the fact that writing aids in thinking better.

The writings I do, such as around the Indian consumer stack and its implications for startup building, or setting out frameworks for PMF means you are thinking aloud in public. Taking intellectual risks in public is often the fastest way to learn, for you have to ensure that you have thought through deeply before you hit publish. Even then you will find that you have made some error – typically some assumption that you have been casual about, or a thesis that doesn’t always hold. You then have to reconcile your position with what you have learnt. All of this thrust and parry makes for greater and faster learning. Eventually this learning informs my investing and helps me do that better. And being a better investor gets me access to better and better, and more experienced founders, and this in turn helps me get better insights and learnings that informs my writing. Each in turn feeds the other.

This essay is close to 10,000 words now, and it is time to bring it to an end.

12. Five years on

Five years back, I was a cautious, wary and somewhat unlikely entrant into venture. The move had many question marks, some from my end, some from Blume and some from the external world. Five years on, through this journey, some of those question marks, both from my perspective, as well as from the external perspective, perhaps no longer remain so.

I have tried to capture this journey, and this transition, from both internal and external perspectives through this essay. If there is a single takeaway from this essay, a singular piece of advice even, is that there are many paths to making it work in venture. If a strategy worked for me, then a different strategy may well work for someone else. For every rule that I hold dear, the opposite rule is held dear by a colleague. It isn’t that I didn’t get this advice early on in my venture career. I probably did. But, like with babies and something hot, no matter how much someone tells you, you have to experience it for it to be absorbed truly.

In the first section of this essay, I mentioned about Karthik’s comment to me, that he wondered when the offer was made, as to whether I “had the courage to pick and live with the risk. We’ve had people who have not been able to live with that risk of writing checks and losing that money, so it’s never easy.” Over the last week or so, this quote is something that I have reflected on deeply.

Backing crazy ideas and risking capital demands a certain kind of courage, and you have to be able to live with the risk of losing that capital, and all of the doubts and perplexities of the decision. But to me, I suppose, real courage is what is demonstrated by the Indian entrepreneur launching their startup. To launch and build in India is hard, extraordinarily hard. To startup then, is to be a bit unhinged, and brave. It demands a certain kind of gumption, a certain madness, a certain unwillingness to listen to reason. It is this spirit, that inspires me, and indeed all of us in venture to pursue our calling.

To serve the Indian founder is a privilege. I am grateful for the leap of faith from Blume that placed me in this position of privilege; and I will never stop paying it forward.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

(Little Gidding, Four Quartets; T S Eliot)

***

Thank you for reading this rather long and winding essay.

I hope this essay, consisting of reflections on my experience and evolution in venture investing, and a stocktaking of the evolving Indian venture and startup landscape, is helpful. If you found it interesting, and / or helpful, feel free to comment below. You are also welcome to send me your thoughts, or any questions at sp@sajithpai.com. Pls do note that I may take a week or so to reply; I will not reply to pitch mails sent at this email address.

I am grateful to Rohit Kaul, Ria Shroff-Desai, Radhika Agarwal, Gauraang Biyani, Karthik Reddy, Anurag Pagaria, Akshat Jain and Nisha Ramchandani for a close reading and critique of an early draft of this piece.

[1] I had however been part of teams setting up new ventures within Times Group, my previous employer. That said setting up ventures within an existing large set up with the comfort of your salary, doesn’t compare with the traditional startup journey and its travails.

[2] Recently, I heard about Clevertap bringing in Sid Malik, the ex-CRO of Freshworks, as CEO. The cofounders are still in the company in CPO, CTO roles. This is a great example of how a fast-growing startup can bring in leadership talent to help it scale further. There are of course, too few examples such as this.

[3] I can’t take credit for coining these. I heard of them first from Sanjay Nath, cofounder of Blume. I believe he heard of it from another VC

[4] For those curious about my productivity stack and the tools I use, here is my stack

- Notetaking – Apple Notes

- Calendar – Vimcal (availability feature is the killer)

- Email – Gmail native client (I had Superhuman but learnt the shortcuts, and saved $30/month)

- Keyboard Shortcuts – Alfred

- Others – Captio (for emailing myself, also use it to take notes on the fly)

I don’t use Things or a task management app, primarily using emails to list tasks and then scheduling them on the calendar using Gmail’s Create Event feature. A key theme of my productivity approach is Calendars > To do lists, because I believe the calendar acts as a forcing function to clarify what is doable, and thus forces you to prioritise your lit of tasks effectively. Another is Processes > Tools, e.g., you can use the best notes app in the world (possibly Mem right now), to input your notes and thoughts, but if you don’t, say, revisit notes and create something from your notes (the process), then it is inferior to an approach where you use Apple Notes (inferior tool) and revisit your notes every Saturday, and take some notes and use ChatGPT to create and publish an article (superior process). Eventually the tool you use has to measured by the output you can generate with it. I believe, great tool + weak process = poor system, but, ok tool + great process = great system.

October 28, 2023 @ 7:30 pm

Thoroughly enjoyed it! Thanks for putting it out.

November 4, 2023 @ 1:56 pm

Thanks Jaideep! Glad it resonated!