It is now just over 20 years since Amazon had its IPO, setting it off on the path to e-commerce dominance and well over $500b in market cap. In these 20 years, Amazon, and its peers expanded across categories, from books and electronics to fashion and even grocery. And in parallel, a ruthless focus on shaving off delivery times and cost ensued, helping reduce buying friction and making online buying even more attractive to the average consumer.

I like to think of these 20-odd years since Amazon launched as the 1st phase of Online Retail. Amazon won the 1st phase handily, reshaping retail in the process. With this reshaped retail however come entirely new challenges for Amazon and its online peers. And in this 2nd phase of online retail, the rules for winning are quite different from what they were before.

Phase 2

What can we expect in this 2nd phase? For one, we will continue to see ecommerce upping its share. The next generation will be far more comfortable with online buying than ours is. And the dodgy financials that bedevil many physical retailers today will soon drag them to death, their share to be grabbed by online merchants.

That said, we are also beginning to see a fight back from innovative retailers, stepping out of the long shadow of Amazon by rethinking physical retail formats and business models to better compete with Amazon and its online peers. In fact, some of these innovative retailers now include brands that were originally e-commerce operations, such as Warby Parker and Bonobos, setting up physical stores to address the need for experience and delight. Amazon, with its bookstores, too has experimented with this intriguing online-going-offline retail model.

In Phase 2, we are also beginning to see a rethinking of online retail itself. Stitch Fix has pioneered a new format of ecommerce that I like to refer to as shipping-then-shopping, stressing personalization and curation to a degree that Amazon hasn’t been able to crack. Poshmark and Moda Operandi have created a retail model where purchasing is only one subset of an overall experience. Not to forget the Vertical e-commerce plays such as Carvana, Houzz etc with their unique takes on the online retail experience.

What do all these mean for traditional retailers, online retailers and online-offline retailers? And Amazon? That is really the subject of this essay.

Essay structure

I have divided this essay into three sections. I will start by looking at how Amazon is evolving itself for Phase 2, including its foray into physical retail, acquisition of Whole Foods etc. How does one understand these moves, and how should one think Amazon going forward?

Secondly, I will examine how physical retailers are competing in and evolving in an increasingly online world. What are new experience-led formats such as Nordstrom Local telling us? What lessons can the successes of indie bookstores and Best Buy tell us about competing with Amazon?

Finally, we will look at what some of the recent successes in online commerce, such as Stitch Fix, Wish etc., tell us about competing with Amazon. If you are a startup looking at entering the e-commerce space what kind of strategy should you adopt to compete effectively with Amazon? Or if you are a VC exploring e-commerce opportunities, how should you evaluate them? Who are the players that are competing effectively with Amazon?

Let us begin then with Amazon and its evolution over the past 20+ years.

Section 1

1.1 How Amazon is evolving

One way to see Amazon’s journey over the past two decades is to see it as moving along the axes in a 3-D graph in an unwavering continuous trajectory. The 1st axis being the number of categories, where it expanded from one (books) to a few hundred. The 2nd axis was time, where it innovated and streamlined its supply chain to reduce delivery time from as much as a week (in 1994) to a few hours today. As it keeps shaving away hours, it runs into a very interesting problem, that no amount of supply chain efficiencies can help it surpass.

You see, I am willing to wait 2 weeks for the Neruda anthology which isn’t available in India, but if you want me to impulse buy the new Cormoran Strike that is on offer, then I need to know it is good, really good. Of course, there are always some products that I know are good, from past experience or from my knowledge, which I can buy on impulse. But for the vast majority of products on offer, the closer Amazon gets to offering instant gratification, the more I need to know that it is good for me, and hence Amazon needs curation, recommendation or some way for discovery to be bundled alongside.

So one key principle that will hold going into Phase 2 is that the more Amazon reduces the time for fulfilment, the more it runs into the need for bundling discovery alongside. This is one way to understand Amazon’s foray into physical retailing via Amazon Books. They solved the 1-week to 1-day fulfillment problem, but how do they solve the 1-hr or 1-min fulfillment problem? Amazon has sensed this can be solved only via bundling in curation / discovery (i.e. recommendations). The best place to understand how curation and commerce are bundled together is physical retail. Let me describe this better.

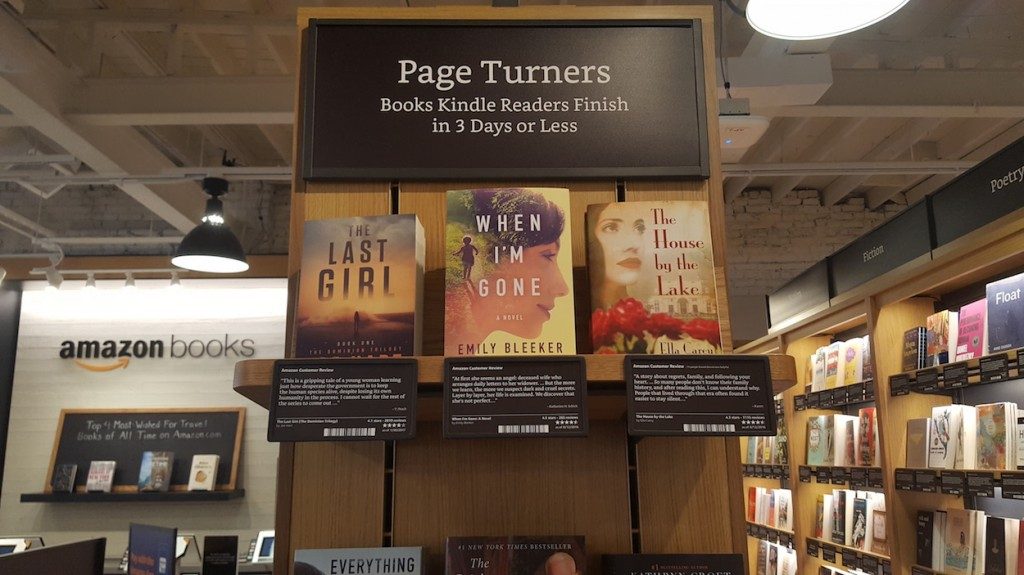

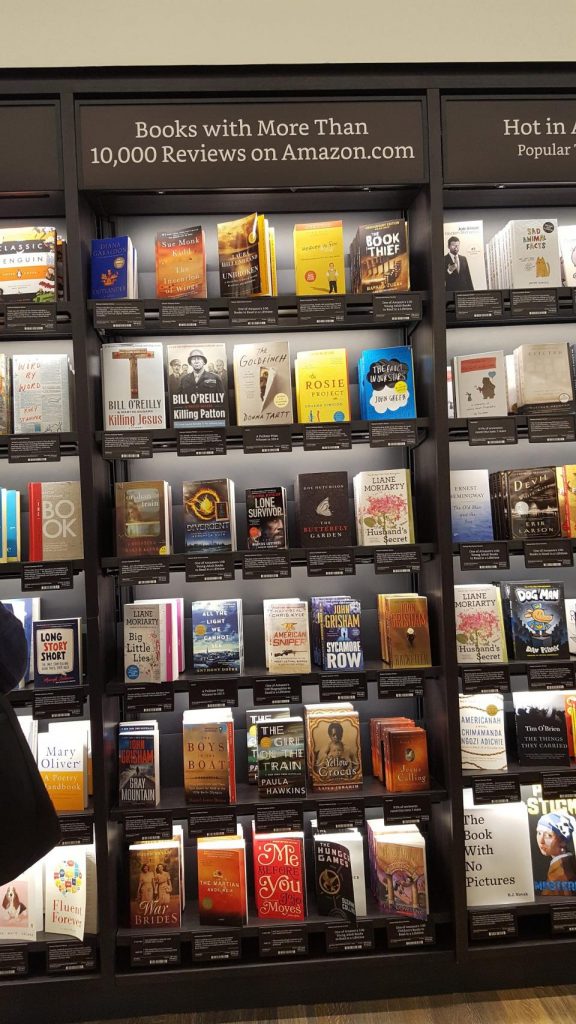

Benedict Evans had a post sometime ago where he described Google as a vast Machine Learning engine, chewing on projects and spitting these out, if it did not suit its “automation + machine learning model”, much the same as a Great White Shark chewing a boat or a dinghy to see if was edible. This is actually a good analogy to understand Amazon as well. Its online operations, from sourcing to delivery, are essentially a set of math models, which it is looking to refine continuously using Machine Learning. To refine these models so as to enable better discovery, it now needs massive sets of physical retail data describing consumer interactions and purchase scenarios, e.g., Do ratings help sell a product better? Does inclusion in a ‘best of local’ list help a product sell more? Etc etc. It is the need for all this data that is leading Amazon to set up stores, as well as buy Whole Foods etc. (Of course in the case of Whole Foods it also means stores that could double up as warehouses to support their online grocery ops too.)

One last way to understand Amazon’s interest in physical stores is also to explore whether the massive data sets that have been generated from over 20 years of online shopping can be leveraged in offline formats. That explains some of the more curious ways of recommendations that have been seen in Amazon Books stores, such as Books with 4.8 star ratings and above, Books finished by readers on their Kindles in <3 days, Books with 10,000 ratings and above etc.

1.2 Online-going-Offline

Amazon isn’t the only online retailer experimenting with physical retail. Bonobos, the men’s apparel now owned by Walmart, was the pioneer, with its Guideshops, followed by the likes of Warby Parker (eyewear), Birchbox (fashion) and Blue Nile (Jewellery) amongst others. Bonobos’ Guideshops are particularly interesting in that its stores are designed for trying on and ordering, but not buying. You order from the store, and the goods are delivered to your home. It is an interesting model, saving on inventory costs and helping them address the need many consumers have of trying out the brand before purchasing. Physical retail minus instant gratification is effectively experience, and that is what Bonobos is selling.

As more and more online players set up their offline branches, they are beginning to influence retail infrastructure too. Derek Thompson, in a recent article in The Atlantic Monthly finds that over the past 5 years, across the top 300 malls in U.S., the retail space occupied by formerly ‘online’ retailers has increased 10-fold. Mall owners want these online-going-offline stores given that they are popular with millennials. These stores typically tend to be smaller – many of them, such as Bonobos above, don’t carry inventory, and “It may be increasingly common to leave a mall having spent a couple hundred dollars without one bag to take to the car.”

One way to put all these ‘experiments’ – such as Amazon which is adding discovery/curation to fulfillment in its physical stores, Bonobos which is happy to stress solely on the experience and a Warby Parker, which offers fulfillment and experiences – in perspective is to see the traditional shopping as a mix of discovery, experience and fulfillment. What online stores are trying to do is to try and play with this mix. Bonobos Guideshops deconstructs experience and fulfillment. Conversely, Amazon Books is trying to add discovery to fulfillment.

Hans Tung, a VC with GGV Ventures which has a strong China focus, uses the phrase new retail to describe these online-going-offline initiatives, definining it as “using technology to digitize and automate offline stores”; in the process rethinking format, operations and the experience itself. China is an interesting place to spot these online-going-offline initiatives. Xiaomi has its Home store, Alibaba its Hema stores etc.

1.3 Prime, Dash and Amazon’s 3rd axis

Back to the 3-D graph and the 3rd axis, which is purchase friction, which Amazon has been working to systematically whittle down. Innovations such as 1-click shopping, Prime and recently Dash are best understood in the context of removing frictions in the buying process. Both Prime and Dash are worth exploring in greater detail given the implications they hold for two rather unrelated industries – the entertainment and advertising sectors.

Prime is fairly well-known and understood, so I will stress Amazon’s focus on “feeding the Prime flywheel” via free video. As Bezos put it in his 2015 Letter to Shareholders “Prime members who watch Prime Video are more likely to convert from a free trial to a paid membership, and more likely to renew their annual subscriptions.” Amazon is on course to spend $4.5b in 2017 to commission video content, making it a key player in the streaming content business, right there with Netflix, Hulu and HBO. For these players, their core products are becoming Amazon’s complement to Prime.

Let us move on to Dash, a small internet-connected device with a button that you press to order a product from Amazon. Each Dash is earmarked for a specific SKU of a brand such as Snickers or Tide. Dash is an interesting attempt at reducing repeat purchase friction. In addition to Dash, Amazon also offers prescheduled deliveries or subscriptions to make repeat purchases easier.

These repeat-purchase solutions – Dash, Subscriptions – are particularly interesting in that they disrupt the existing model of repeat purchases and all the variables involved there – reminder ads, offers from manufacturers etc. Reminder ads are a key part of ad spends from established brands. Dash or subscription plans from the likes of Dollar Shaving Club obviate the need for reminder ads, thus impacting a key chunk of the ad market. As I highlighted in a recent post, competitors to existing advertising solutions in the future will look nothing like an advertising product.

Thus Amazon’s attempts at reducing friction in the online buying process seemingly disrupt two rather unrelated industries – Streaming Video and Advertising. In fact on the latter Amazon has already built out an over $1b business (or $2.5b if you believe WPP), led largely by what are called sponsored products ads, where companies pay to have their products displayed prominently when customers are served search results for a category, like laptops.

Over the past couple of years, Amazon’s stock price has doubled, and its market cap has reached nearly $550b. There is an overwhelming conviction in the press that Amazon is now the most innovative company in the world, on the back of the fast-growing ecommerce and AWS business, and the numerous innovations that pour out of Seattle. A key reason investors are betting on Amazon is because they believe that the Total Addressable Market (TAM) that Amazon can aspire to address is effectively the global retail industry at ~$22 trillion. In comparison Google and FB are bounded by the ad sector’s TAM which is $0.5 trillion.

As Amazon begins to cover more and more ground over the retail sector – last year Amazon is estimated to have accounted for nearly 40% of the U.S. e-commerce sector, effectively about 4% of overall retail in the U.S., what does its impending dominance mean for physical retail? Is it doomed for extinction? How are physical retailers shaping up as their industry is transforming? Let us explore this in Section 2.

Section 2

2.1 The post-Amazon retail store

The easiest way to compete with Amazon, or for that matter any formidable competitor, is to offer what they can’t. Thus retail experience becomes a key proposition to build on for physical retailers. Another proposition that physical retailers, especially booksellers, have stressed is curation and enabling discovery. The Post-Amazon store is thus being built around experience, selling expertise, curation and discovery. This strategy is reflected in the new retail designs that are emerging in the U.S. and other western countries in this Post-Amazon era, such as in Nordstrom’s ‘Local’ initiative.

Nordstrom Local is focused around expertise, discovery and experience. At Local, a much scaled-down version of the traditional Nordstrom store, consumers can meet with fashion stylists for advice, try out the clothes on display, have their detox juices and get their manis done. Everything but buy the clothes and walk out with the shopping bags. Instead, you order and get the goods sent home, as there is no inventory on offer at the store; or you can order online and pick up the order from the store. It rather resembles Bonobos’ Guideshops, which we encountered earlier.

On to expertise. Beyond advisory services such as Nordstrom Local or even the Genius Bar at the Apple stores, expertise can also be sold to consumers as a service. We see this in the workshops being offered at some of the Apple, Home Depot and Lego stores, to cite a few. Closer home, Usha’s Hab store in Mumbai offers worksops around sewing and knitting. There are dual advantages here – it helps build an additional revenue stream, and also helps mark out your core customers.

What these additional offerings also imply is a fundamental reworking of the traditional retail format itself. Primeness of the location matters less if you are not focused on making sales out of the store. Sizes of the retail store also come down if inventories are minimal. Thus, from a recent New York Times story “Instead of the arms race for the biggest location on the most desirable street, a new model focused on multifunctional integrated stores is gaining currency; less storehouses of product than event spaces, classrooms, community centres, showrooms or studios.” Not for nothing did Angela Ahrendts, Apple’s retail head, recently call their stores Town Squares.

2.2 New Retail Business Models

Beyond retail formats, retail business models could also end up getting fundamentally restructured. What if like expertise, curation is also unbundled and sold? Presently, it is offered for free or rather bundled with commerce itself, such as at bookstores and fashion outlets, monetized when the consumer buys the product. With showrooming (when the consumer checks out the product in the store but pick it up cheaper off the net), curation and commerce get unbundled and there comes the possibility that you may not monetize that curation at all. If so how could retailers get consumers to pay for it? In what scenarios could retailers charge for curation alone?

I have wondered a lot about this, specifically in the context of independent bookstores, which is a particular interest area of mine. Could independent bookstores charge separately for curation like museums do? Imagine an artfully-curated display of books on a particular topic, e.g., Happiness, Idea of India, AI etc in a closed section open only for a small charge? I am not entirely sure. What may be a better route could be to create new curation + commerce bundles – say a book of the month selection mailed to ‘members’ or subscribers. Heywood Hill in London does this quite well curating book boxes for subscribers as far away as USA on various topics – history, gardening, food etc.

One interesting implication of this rethinking and reworking of the store is the transformation of the transaction between retailer and buyer. In the ‘80s a woman would step into Nordstrom and walk out with two skirts and a scarf. Today her daughter may well buy the same or fewer, but she is also buying a raw-pressed juice and getting her nails done during her shopping. Thus a lot more service is beginning to get sold with the goods.

Ulta Beauty is a great example of this servicization trend. Each of their stores has a beauty salon, helping them sell both beauty services and products (multiple brands). Ulta is thus far more protected against Amazon than say a Sephora which sells only products.

At the extreme end we will have entire product categories, moving from selling goods to selling services. Transport is the ur-example of such a trend. With on-demand services such as Uber, the consumer doesn’t need to own a car anymore. He is buying miles or hours depending on what service he uses. So what happens to car retail stores (auto showrooms) with such servicization? Toyota’s new retail concept, Drive to Go gives us a clue. Drive to Go’s new Tokyo store is structured as a car-rental cum café and not a car showroom.

2.3 Learnings from Amazon surivors

Retailers who have survived against Amazon offer some interesting learnings. Best Buy, an electronics retailer, is oft-cited as the textbook example of how to stand up to Amazon. Best Buy has managed to survive by a clutch of interesting strategies – using price-matching to combat showrooming (even at the risk of losing money on the sale), enhancing the service element in the transaction by adding in free consultation on what to buy and how to install, and using the stores as warehouses for shipping online orders (as much as 40% of its online orders are shipped from its warehouses). Independent bookstores who have had an even longer history of combat against Amazon offer valuable learnings too.

Independent booksellers have fortified themselves by stressing on the two areas Amazon cannot compete on – offering discovery through effective curation, and offering a great experience via book readings, workshops, and coffee. True, many of them have also benefitted from the huge outpouring of support for local retailers by passionate residents, but this alone wouldn’t have been enough without a compelling value proposition.

One particularly interesting business innovation that indie bookstores have launched (and from which other embattled retailers could adopt) is membership. CostCo, which allows shopping only to its members is the definitive example here. Museums and Zoos too, both curation heavy bsuinesses have strong membership schemes. Membership allows a retailer to get some cash in, identify their most valuable members and get these members committed to spending their cash in your store (via offering permanent discounts etc).

We thus have something of an Amazon-proofing playbook for physical retailers now, painfully acquired learning from two decades of scorching competition – Build a strong services line, offer a compelling experience, stock your shelves to reflect a point of view, use your stores to support your online operations, match online prices etc. That said, what about online retail – is there an equivalent playbook for competing with Amazon online? Are there any equivalent examples of online players who have taken the battle to Amazon? What are the interesting new models that are emerging in online retail. Onto section 3.

Section 3

3.1 Online retailing in the shadow of Amazon

One easy way to understand what kind of online plays are thriving against Amazon is to look at the list of highly funded e-commerce players. Sure, not all of them necessarily compete with Amazon, but many do, and thus this list of highly funded ventures gives us as sense of the winners from the battle with Amazon. This is thus a good place to begin.

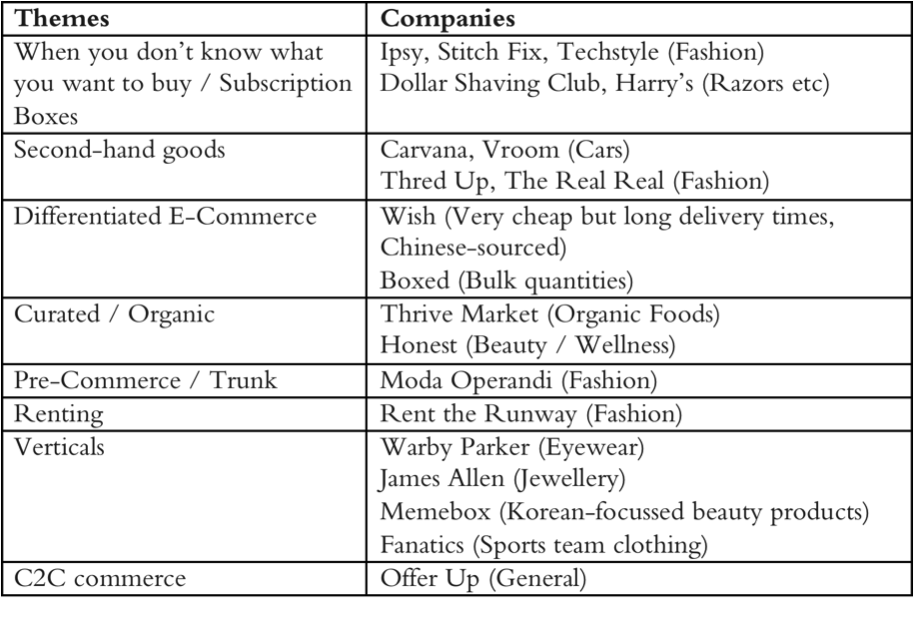

Let us stick with the US for now. There are just over 20 companies that have received over $100m in funding over the past 5 years in the U.S. There are 2 ecommerce enablers (BigCommerce and Magento), which we can remove from the list. Of the rest, these there is only 1 company, Jet.com (acquired by Walmart) that may be considered similar to Amazon, in that it does general purpose ecommerce. The rest fall across various sub-themes in e-commerce, all of which have one thing in common. They are themes that are difficult, though not impossible, for Amazon to execute on, given its DNA.

Amazon’s sweet spot is around delivering commoditized products efficiently leveraging its powerful optimizing models built on sophisticated mathematics and automation. Like Google search, it demands that consumers approach it with intentions. If you know what you want to buy, Amazon can source it from manufacturers and deliver it to you cheaper and faster than anyone else.

Amazon’s sweet spot is around delivering commoditized products efficiently leveraging its powerful optimizing models built on sophisticated mathematics and automation. Like Google search, it demands that consumers approach it with intentions. If you know what you want to buy, Amazon can source it from manufacturers and deliver it to you cheaper and faster than anyone else.

That last line is a particularly interesting one to view the above VC investments through. Even if one of the phrases in that line changes, then Amazon will not find it easy. Each phrase in that line is actually akin to an investing subtheme, offering an opportunity for a startup or two to exploit and grow. To elaborate, let us look at what happens when consumers don’t know what they want? Discovery becomes critical to the process, either through recommendations or curation, both alien to the way Amazon works.

3.2 When you don’t know what you want to buy

Subscription boxes across cosmetics (Ipsy) and fashion (Stitch Fix, Techstyle) have emerged precisely to cater to customers who don’t know what they want to buy, but are happy to get a company to do it for them. Ipsy, Stitch Fix all have human intelligence in the form of stylists who recommend products. Stitch Fix in fact has 3,500 of them and combined their taste and intelligence with past data to create a powerful recommendation engine. It is a distinctive and fascinating business model that is worth going in to in some detail.

Stitch Fix’s recommendation engine sends 5 or so garments monthly to its subscribers. If they don’t like any of the outfits they can send them back. This helps Stitch Fix iterate on and improve the recommendation process. This is thus a shipping-then-shopping model as opposed to Amazon’s shopping-then-shipping model. Stitch Fix closed 2016 at revenues of $730m and has been profitable for the past 3 years. Inspired by Stitch Fix, Amazon launched Prime Wardrobe, its try before you buy service. But I am not entirely sure it will succeed, for the following reasons.

Stitch Fix’s use of human stylists, its enhanced recommendation engine and its distinctive try and then buy model all form a tightly-integrated set of decisions. Amazon on the other hand has an entirely different model with minimal human inputs, entirely ML-led personalization, focus on commodity products and extracting efficiencies, and thus a shopping-then-shipping model. Amazon has successfully rolled out private labels focused around basics (commoditized products such as White T-shirts, innerwear etc), but I am not sure it will be easy for Amazon to transform itself to compete with Stitch Fix, a fashion and taste focused e-commerce co.

3.3 Other themes and businesses

Of the other themes and businesses, I found Wish particularly interesting in that it targets consumers willing to wait a long time – for ultra-cheap goods, shipped from China. There is a kind of deliberate inconvenience built into their business model as is for Boxed, where the customer needs to order in large quantities, in order to unlock the lower prices they desire. A similar inconvenience-oriented business is India’s Milkbasket, which only delivers groceries and other smaller consumer goods in the morning between 5-7am.

These inconveniences need to be seen as features, not bugs. They result in a distinctive business model driving logistics costs well below that of a general e-commerce player. Bezos has built Amazon to deliver goods fast through the day in any volumes the customer desires, at the lowest cost. But when these competencies cease to matter – when customers are happy to wait, or buy in ultra-large quantities or at inconvenient times (say early morning), Amazon loses its advantage and is forced to compete on level ground.

Also away from Amazon’s comfort point are business models such as secondhand goods (Carvana, Thred Up), renting (Rent the Runway), precommerce (booking luxury fashion in advance as in Moda Operandi) etc. It isn’t that Amazon can’t get into these spaces. They will possibly take a crack at it one day. It is just that the way it has been built – to go after commoditized spaces with low prices and super-efficient logistics makes it difficult to target opportunities that need curation, don’t need quick deliveries, renting etc. Each business model needs an entirely different DNA.

How should Entrepreneurs & VCs pick spaces?

What kind of ideas will work for companies going up against Amazon? Or even better what are the Amazon-proof spaces that exist today that Entrepreneurs can enter safely?

Sriram Krishnan, a Silicon Valley executive had a very interesting post sometime back titled “Building something no one else can measure”. It expanded on a tweet where he described competing with major platform companies by optimizing a metric they can’t measure. I would hazard a corollary to this: compete on the opposite of a metric that the platform is optimizing for. In the case of Amazon, then you would not compete on range, price or delivery time.

To explain this better, let us take the first theme – offering something that the customer didn’t know they wanted to buy – here you are optimizing for better curation, i.e., limited SKUs which is the opposite of what Amazon wants. As ‘The Everything Store’ Amazon has to have / offer every single SKU in the universe. Meanwhile a curated store can just offer 10,000 interesting SKUs and be a relevant proposition. In fact one may well argue the better the curation the smaller the choice set or SKUs it should offer. This explains why vertical players such as Houzz, Warby Parker, Yoox Net a Porter have done well.

Curation itself comes in various flavours – expert-driven ones such as in Houzz and Techstyle (typically associated with vertical plays) or value-driven curation such as in Honest Co or Thrive Market.

Another good example is prescheduled deliveries such as by Stitch Fix or Techstyle, competing at the opposite end of Amazon, which is optimizing for speed of delivery. Prescheduled or subscription products also make pricing comparisons irrelevant – you don’t know what you are getting, so how do you even check the prices – hitting Amazon which is optimizing for the lowest price. Quite cleverly, this takes away the competitive advantage Amazon has in logistics and prices, bringing both to level playing ground.

In a recent article, Alex Evans, a VC, analyzed potential second order effects as e-commerce expanded. One consequence he argues is that as e-commerce becomes frictionless, it will become easier and easier to rent instead of buying. Netflix streaming and Uber hiring have replaced owning movies and cars respectively. He says “the same principle will hold in commerce: the cheaper and more frictionless access becomes, the less stuff we’ll need to own”.

We can already this happening in the fashion space with businesses such as Rent The Runway and Bag, Borrow Or Steal. Interestingly the option of renting as opposed to owning also sparks experimentation. You become open to renting out that adventurous dress for that one-off occasion, whereas earlier you hesitated from buying it because you wouldn’t use it anymore. I can clearly see this happening with Sarees in India. It will also be interesting to see the rental model expand beyond fashion and enter other spaces. Co-owning (similar to timeshares or with private planes, as in NetJets) could be another business model that could emerge in addition to renting.

Lastly, the Servicization argument I set out in the previous section, on physical retail, holds good here as well. A good example is Carvana or Vroom, both secondhand online car sellers, each with their own distinctive bells and whistles, e.g., Carvana operates gigantic car vending machines where prospective buyers can borrow a car and drive it around for a week before deciding to buy it. There is a huge service component to this business, as well as the need for intermediation between seller and buyer, moving it away from Amazon’s sweet spot.

Summing Up

I started this post with a metaphor about Amazon and the shadow it cast over the retail world. It is a useful metaphor to view the rise of new online players as well as the reemergence of some of the traditional physical retailers. They are all emerging out of Amazon’s shadows, or the perhaps the shadows have shortened. It is high noon on Amazon’s Day One, and it is time for the fight to begin.

References

Beyond Amazon and Alibaba: what’s next for e-commerce?

The Artist Formerly Known as Ecommerce

Retail, Ownership and Deflation in the Last Mile

Long Live Retail: Fashion Startups Finally Learned Why Physical Stores Still Matter

What E-Tailers Can Learn From Netflix

The 4 Reasons Why 2017 Is a Tipping Point for Retail

The Death Knell for the Bricks-and-Mortar Store? Not Yet

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/13/fashion/shopping-online-retail.html

Best Buy’s Secrets for Thriving in the Amazon Age

Chamath Palihapitiya on Amazon – Reference 1 and Reference 2