The term ‘CM2+’ (pronounced CM2 positive) is frequently used in startup conversations, but often its true meaning and significance are misunderstood or not apparent. In this note I explain it significance and why becoming CM2+ is a key goal that early stage startups should strive for, and why it is integrally linked with getting to PMF (product-market fit).

In the essay I have used CM2+ as a shorthand for ‘CM2 positive’ and CM2- as a shorthand for ‘CM2 negative’ ventures.

First, some definitions

CM2 is part of a family of metrics which includes CM1, CM2 and CM3.

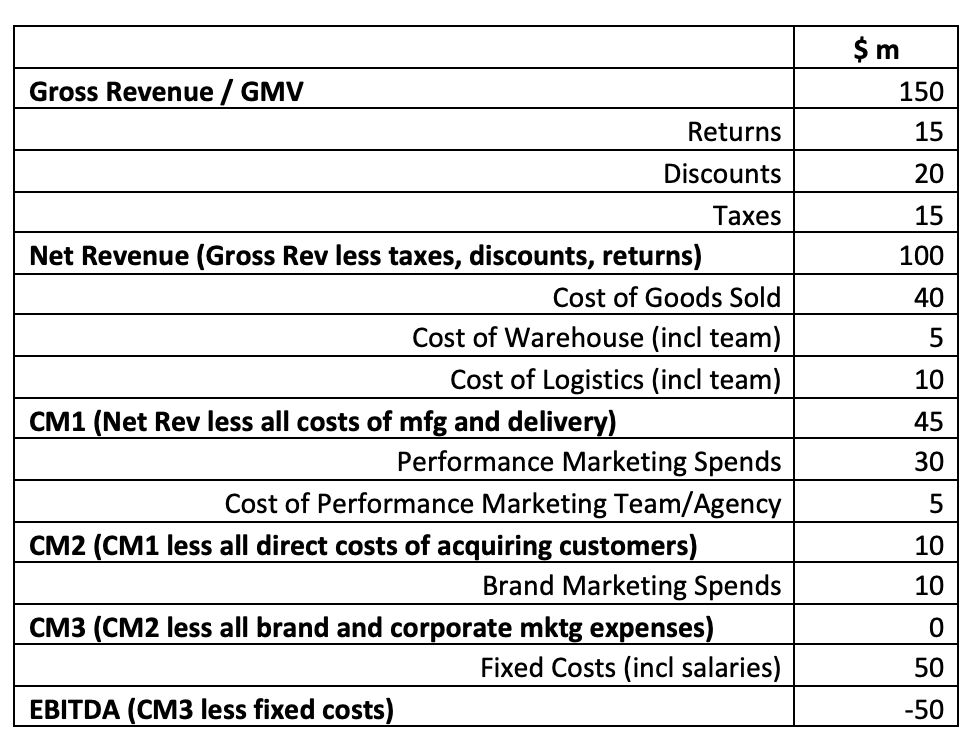

Net revenue = gross revenue less (or net of) taxes, cancellations and returns. This is effectively what the customer pays you, which you can use for your business needs (taxes have to be kept aside to pay the government)

CM1 (Contribution Margin 1): Net Revenue minus all costs associated with manufacturing and delivering the product. This includes all direct, variable, and attributable costs like warehouse rental and staff costs. Also referred to as ‘gross margin’.

CM2 (Contribution Margin 2): CM1 minus direct marketing costs, such as performance marketing expenses. Essentially, CM2 = Net Revenue minus all variable costs involved in customer acquisition, and product creation and delivery.

CM3 (Contribution Margin 3): Less common than CM2, but effectively CM2 minus brand marketing costs. CM3 less all fixed costs = EBITDA.

To illustrate with a hypothetical example,

It is possible that you may encounter definitions of CM1, CM2, CM3 different from the way I described. This is because these are not accounting terms from the field of corporate finance, but rather metrics from the field of startups and venture. In facr these these terms CM1, CM2, CM3 are not frequently encountered outside the startup world. I have not been able to clear place who invented it. From my research it was either invented by Rocket Internet per this tweet

…or growth investors who saw in them proxies of future profitability. The below is from Avnish Bajaj of Matrix Partners in a podcast.

“….none of these terms are in the accounting or financial world anywhere.…So it has been invented by the internet. I use it, you use it. And the reason we use it is because in the, in the internet businesses you are often underwriting future cash flows. You are saying kabhi na kabhi paise banega (you will make profits at some point), but you can’t underwrite that. So in order to get proxies for those future cash flows, all of these margins have been created and frankly, I have learned some of them only over the last five, six years from some of the later stage investors who tend to use it more. Because remember later stage investors are trying to underwrite profitability and in the absence of current profitability they need proxies for future profitability. So if I have a one line description of contribution margin in the internet world, it is proxies for future profitability.”

Why CM2+ matters

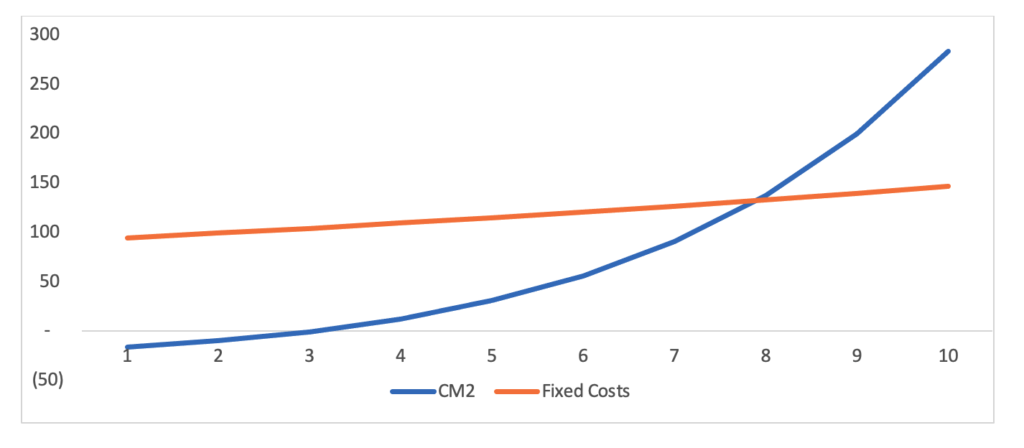

As a business scales, all costs and revenue grow. However, if a business is to become profitable, revenue should grow the fastest, followed by variable costs, and then fixed costs slowest of all. The widening gap between revenue and variable costs leads to an increasing CM2, which eventually covers all fixed costs, making the business profitable. This is why CM2 matters. A positive CM2 assures us that the business has the potential to be profitable in the future.

Consider a SaaS startup growing at a 30% YoY rate:

– Starting Net Revenue: $30K (increases by 30% YoY)

– Fixed Costs: $90K (increases by 5% YoY)

– Variable Costs: $50K (increases by 10% YoY)

In this scenario, the startup’s CM2 will grow over time, allowing it to double down on growth and eventually cover all fixed costs.

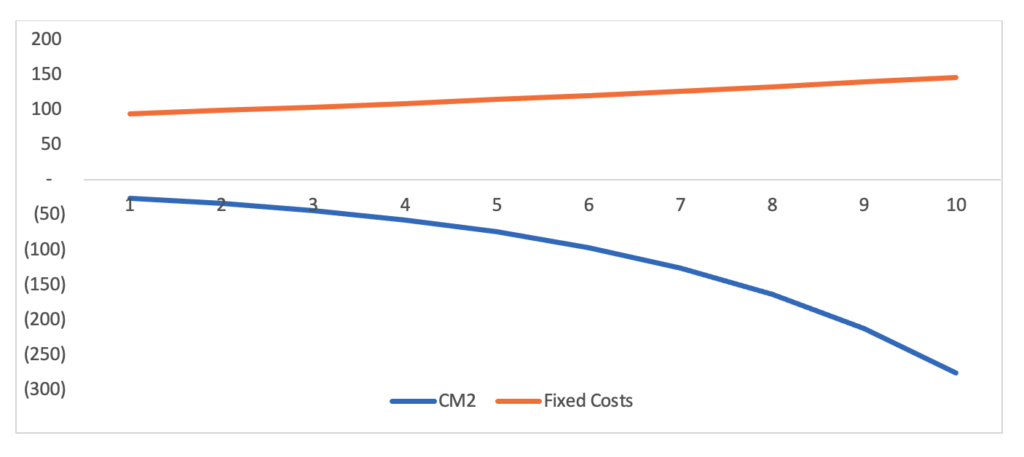

A positive CM2 is crucial, and this is determined by the different growth rates of the revenue and variable costs. Essentially the revenue curve slope should be far steeper than the variable cost curve slope. If a company can’t control its Customer Acquisition Costs (CAC) as it scales, say due to channel saturation, it will never become profitable.

As you see from the above chart, when variable costs rise on par with revenue, CM2 will never cover fixed costs.

Why CM2+ is kinda akin to PMF

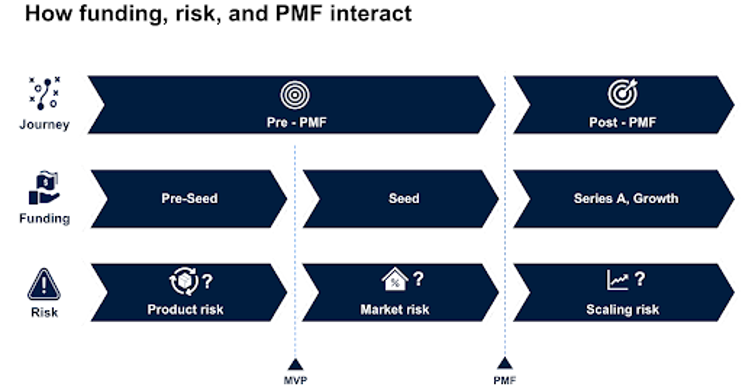

PMF or product-market fit is a vast, complex topic with varying takes on what it is and how to know if you have achieved it. (Here is a post of mine that you can refer to for my definition of PMF.) Founders looking to figure if their startups have achieved PMF can use sustained CM2+ as a rough thumb rule for achieving PMF. Let us unpack this.

Focusing on scaling or rapid growth when you are CM2- means that you are growing a fundamentally broken business. CM2- businesses lose money on every customer acquired and serviced. Logically, you are better off at this stage, not on growing the business as much as getting the business to CM2+ by showing that you can make money on every customer acquired and serviced. Once you hit CM2+ on a sustained basis, you know you have nailed it. Now you can scale it by relentlessly focusing on growth (and tracking that you don’t slip into CM2-, and if you do slip, then pausing growth to figure out how to iterate on the product to get back to CM2+).

Thus a sustained CM2+ startup is one that has a higher revenue slope than variable cost slope, with clear predictability of revenue and costs. This assurance is effectively PMF. It is the nailing before the scaling. Thus as a shorthand, PMF is effectively becoming CM2+ on a sustained basis.

Investors and CM2

Most Series A investors will need the business to be CM2+ before they invest. Historically Series A investors have come in when the business hits PMF and effectively they are using CM2+ as a proxy for PMF. So what happens if you are a startup that is not hitting CM2+ but are raising Series A funds?

One way is to disaggregate the business into older segments (cities or products or cohorts) and newer ones, and show to the VC that the older segments are CM2+ and there is a historical path from CM2- to CM2+ that the older cities and cohorts have consistently achieved. But if your older segments are CM2-, then well, you probably shouldn’t raise a Series A, and should reengineer the product and product proposition to get to CM2+.

Seed investors will be more willing to look at CM2- (though they will want to see that it is CM1+). After all a key risk that seed VCs mitigate is market risk, and helping the startup figure out an effective GTM that helps cover the cost of acquiring customers is an area of expertise for most good seed VCs.

Do note that if you are selling a high LTV to CAC product, with say strong lock-ins or repeats, then a Series A VC will be open to a CM2- startup at the time of investment; the VC is presuming that over time the high LTV will grow revenues enough to cover the CAC, and thereby reveal itself in the startup becoming CM2+. Again a high LTV business will also reveal itself in the older cohorts growing rapidly or being CM2+ already.

TLDR

CM2+ve effectively means your incremental revenue covers the cost of generating the revenue. When you achieve sustained CM2+ve status with a higher revenue growth rate than variable cost growth rate, and reasonable predictability of those revenues and costs, you have essentially achieved PMF. You have nailed it. Now you can go all out and scale it.

Am happy to hear your thoughts on the above, and any questions you have. Feel free to comment, and I will reply to your comments.

Thanks to Anurag Pagaria for helping me in drafting parts of this note, and reading an early draft of this piece.